When I began working on a book about Soviet propaganda, it was not a sexy subject—not nearly as sexy as it has become, if one is to judge from flashy headlines and “fake news”.

The Cold War seemed rather passé and even quaint a few years ago. More recently, stories that echo the heightened and polarized rhetoric of that era have again been breaking news.

For me, that is surreal. And yet, it is just one more example of why history matters.

In many contexts today, doing history is about seeking a more truthful reflection of the past. It means gaining access to archives and oral histories, confronting difficult stories, and having meaningful conversations about personal experiences and perceptions.

Too often the quiet work of archivists and librarians remains cloaked in secrecy. Indeed, if “fake news” is now a thing, we may all thank the stars that they are squirreling away the information that historians will need generations from now, preserving documents, oral recordings and rare books that allow us to gain perspective and insight on the past.

This book is the result of many hours in the archives, working to make connections, fill in gaps, or learn to live with missing information. It is also the result of the painstaking work that archivists and librarians have accomplished, to diligently preserve bits of a larger puzzle and to make the records accessible. Archivists at several different institutions had kept bits of the story about the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society, answered reference questions and advised on access to materials that had previously been classified. Their theoretical work also guided me. The stories told in oral histories and archival documents did not align exactly, and allowed for a deeper understanding of the era.

Although Propaganda and Persuasion began as a dissertation before I had begun to work as an archivist, even then, it was an archival project.

First, I wrote a finding aid for the VOKS papers, copied from the State Archives of the Russian Federation (GARF) and brought to the Centre for Research on Canadian-Russian Relations at Carleton University in Ottawa. (These papers may now be found at the University of Alberta Archives). The VOKS papers demonstrate the support the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society had from the USSR. The All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS) was a Soviet government agency responsible for providing the material support to friendship groups around the world. It is clear from his correspondence that the VOKS representative in Ottawa, Vladimir Burdin, closely monitored Canadian public opinion, interacting with Canadian citizens and government officials in official and more informal roles.

Then, while waiting for an Access to Information (ATIP) request to be processed, I began doing oral history interviews with former members of the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society. If the end of the Cold War made it possible for activists to speak openly about their activities, it also allowed archivists to collect responses to formerly restricted archives. I was struck by how individuals spoke back to the archival record, both literally, in allowing oral history interviews; and figuratively, in adding notes to existing archival collections. In the process, they created new archive stories. Several challenged their own perceptions of past events.

In the context of the postwar blacklists, it is a bizarre experience to see faces and names come together in the archives, where the listed speak back to the lists. My interviewees were counting on me to make their voices heard, but how could I square their stories with the written record, and the information now available about people’s experiences in East/Central Europe? I came out of this impasse by bringing theories of narrative, and social history to the archives, to flesh out the material and to approach the complicated stories of lives lived during the Cold War.

If today we can recognize the false or exaggerated claims Dyson Carter and the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society propagated in publications, events and tours, we can also see the sincere desire some Canadians had to believe that in the Soviet Union, an egalitarian society existed. Understanding the attraction the group had for left-leaning Canadians allows us to better grasp the persuasive effect of the material it was distributing. Little clues in the Irene and Louis Kon fonds at McGill University, the Novosty Press Agency papers at Carleton University, and the Laurence Nowry fonds at the Canadian Museum of History were invaluable in considering how and why some Canadians were attracted to the Society’s messages. Archival and oral history references confirmed that the Soviet authorities valued Dyson Carter, the president of the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society, for his entrepreneurial style and energy.

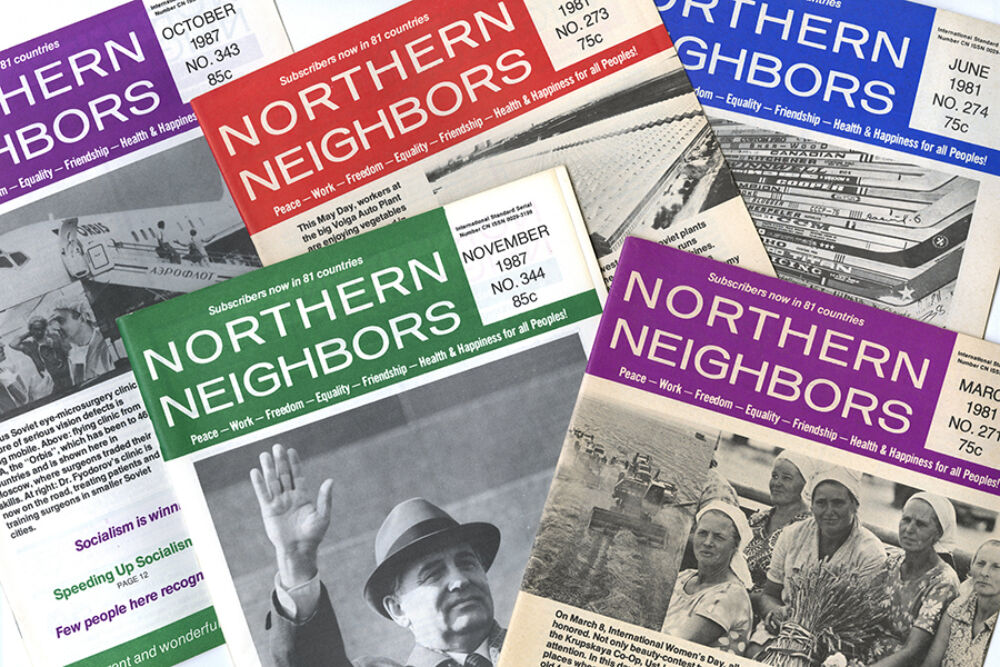

I spent long hours reading the publications produced by the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society in the reading room of Library and Archives Canada (LAC) at 395 Wellington Street in Ottawa. For forty years, from 1949 until 1989, Dyson Carter, a Canadian based in Toronto and then Gravenhurst, Ontario, published what was essentially Soviet propaganda, re-tooled for a North American audience. From today’s perspective, it is much easier to recognize manipulated facts about Chernobyl or the Soviet invasions of Hungary and Czechoslovakia, but subscribers to these pro-Soviet magazines, most of whom already admired the USSR, read them as proof their political views were justified. Also at LAC, the Dyson Carter fonds showed just how he spliced the material from the USSR to create the upbeat, never-wavering pro-Soviet magazine Northern Neighbors.

Access to the files of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and External Affairs held at LAC showed the concern the Canadian government had about the impact of the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society. These archives also reveal the Canadian government was paying close attention to the patterns of Soviet persuasion over a longer period, where the friendship societies served as ostensibly non-partisan public relations agencies, diffusing the Soviet perspective on international events.

The Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society was participating in the information war, which characterized the Cold War era, where the balance of power was maintained amid efforts to persuade people of the cultural, scientific or technological supremacy of the players. In studying the subtle and more blatant attempts to influence public opinion in North America, the history of the Canadian-Soviet Friendship Society suggests the impact of narratives (and counter-narratives) about truth in Cold War Canada.

And because it is now possible to tell this story with reasonable certainty and modest conclusions, it reminds us that in a world of “fake news,” archives and libraries have real value.

Posted by Jennifer Anderson

October 3, 2017

Categorized as Author Posts

Tagged canadian-soviet friendship society, cold war, dyson carter, history, history of the left, politics, soviet, ussr

In Memoriam: Thibault Martin Launch of UM Archives Event with Snacks!