Canada’s centennial year was an exhilarating time to live in this country. The 1967 Centennial was a mixture of historical pageantry, earnest civic boosterism, and a nationalistic pride that seemed to surprise many, all combined with a certain ‘60s funkiness. Journalist and popular historian Pierre Berton later remembered it as “an awakening of the spirit that seduced us all.”

It wasn’t a wonderful time for all Canadians, of course. The monstrous residential school system was still operating, while the structural injustices of our society were not much changed by the countless small and large Centennial “projects” that popped up everywhere.

But, officially, all Canadians were encouraged to create something to celebrate the past and the future of what might become a new kind of Canada. The most famous of the Centennial projects was Montreal’s Expo 67, the wildly popular world’s fair, but today nearly every Canadian community still has a “centennial” hall or building erected to celebrate that anniversary.

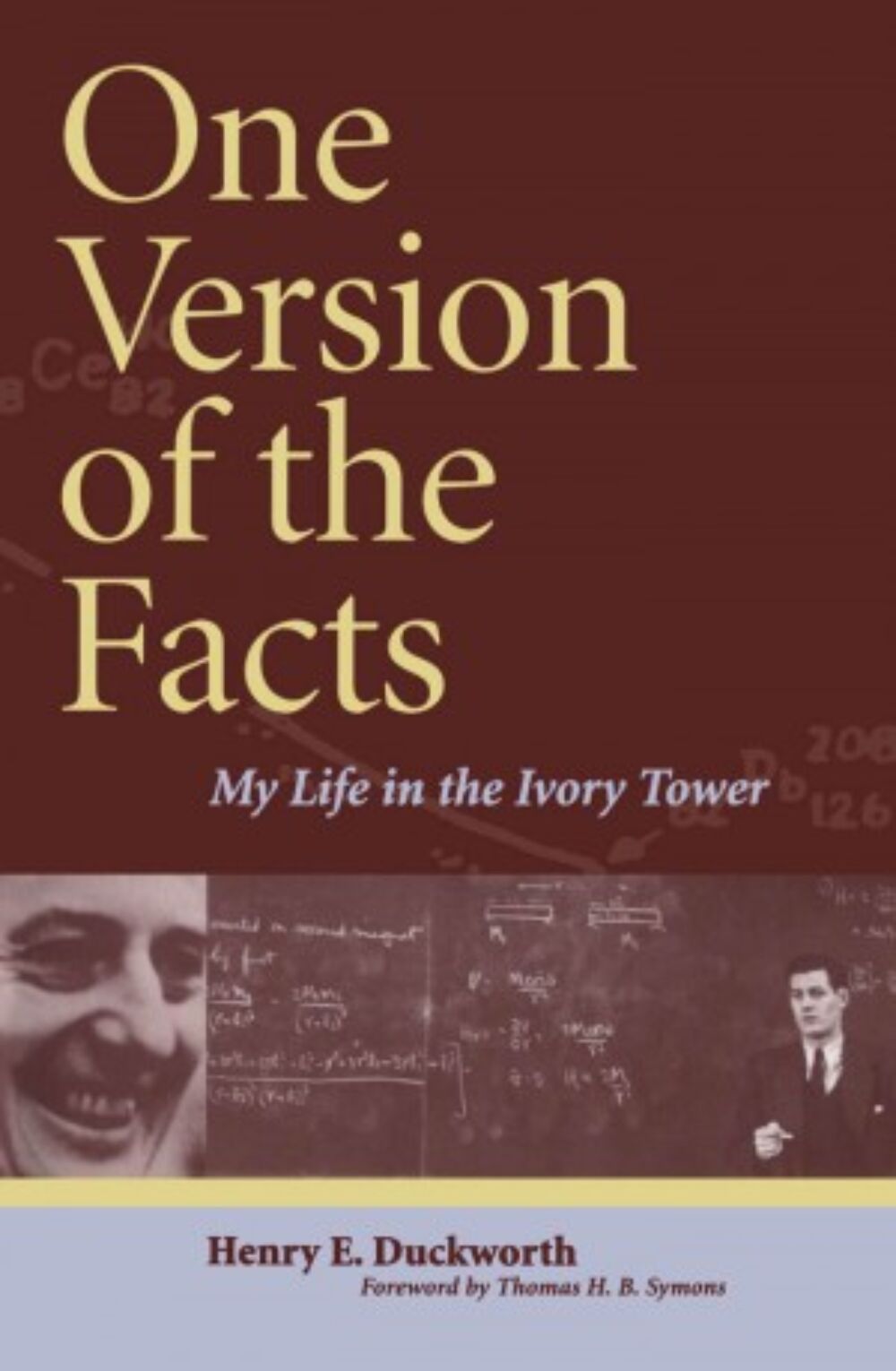

University of Manitoba Press was officially founded in January 1967. I like to think that our press was one of those Centennial projects, and that we still carry some of the spirit of that year. If the press had a founder, it was Dr. Harry Duckworth, then Vice-President Academic at the University of Manitoba, so perhaps in a way we were one of his Centennial “projects.” Dr. Duckworth was an internationally-respected physicist who had studied at the University of Chicago at the same time that Enrico Fermi was at work in a lab under the campus stadium on the first nuclear chain reaction. Duckworth was a man of wide interests, humanistic tastes, gentlemanly manners, and a sly sense of humour. He was also a proud homegrown Winnipeger, and would later become a popular president of the University of Winnipeg and return to the University of Manitoba as chancellor.

Early in 1967, Dr. Duckworth hosted an international conference on physics at the University of Manitoba, and it is no coincidence that one of our first publications was the Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Atomic Masses. It is still our single longest book, clocking in at 904 pages.

While the initial impetus for the press’s creation might have been to have a home for this scientific tome, I imagine that more than this inspired Duckworth. Part of the Canadian cultural nationalism of the late 1960s was the urge to build new institutions and structures that would help Canadians talk about their own lives, culture, and history from a uniquely Canadian perspective.

One important manifestation of this was the birth of a full-fledged Canadian book publishing industry, as new book publishers sprang up all over the country, anxious to publish Canadian writers and to reach new readers.

While a fledgling university press in the middle of the prairies was not as bohemian or edgy as the new literary and political publishers, the need to create western Canada’s first university press was most definitely part of that same feeling. In fact, the press’s original “Statement of Policy” was implicit that one of its mandates would be to publish books “dealing with topics of particular interest to those living in the Prairie region.” Our publishing list soon grew to include books that dealt with national issues and which reached readers across the country, but we’ve also remained firmly rooted in our home community.

For the rest of this year, to help celebrate our 50th anniversary we will host an ongoing series of blogs about the press’s history. These will talk about books we’ve published, celebrate our authors, and even explore some controversies we’ve been part of. It won’t come close to a complete picture, or even an objective one, but we hope it will be a way to explore some of what it has meant to be a scholarly publisher in this place and in these times.

Harry Duckworth later entitled his memoirs One Version of the Facts (long before the much more ominous phrase “alternative facts” appeared). There is naturally no one “official” version of what a university press history should be, but like Dr. Duckworth we’ll do our best to present at least one or more “versions” of our story over the next year.

And as we move into our fifty-first year, we will also strive to keep alive in the press and its books some of the character of the year of its birth—inquisitive, open and critical, proud of its place, and committed to independent voices.

Posted by U of M Press

February 14, 2017

Categorized as UMP at 50

Tagged 1967, books, centennial, community, culture, founder, history, manitoba, prairie, publishing

Judy Parker on Selling UMP Esyllt Jones on Nostalgia