A Liberation through Claiming – A Conversation with Gregory Scofield

From Masculindians: Conversations about Indigenous Manhood

Sam McKegney: Can I ask you about embodiment and sensuality in Love Medicine and One Song? In “Ôchîm ̈ His Kiss” the kiss of the beloved is described as “maskwa pawing / all his winter hunger,” (maskwa is the Cree word for bear) and the speaker in the poem continues: “so I yield up roots and berries / and lie back / my whole abundant self ”. It’s a beautiful image that demonstrates agency because it’s a decision: “ I yield up.” And yet to yield oneself up is to be totally vulnerable. Can you speak to the tensions involved in that need for physical intimacy along with the danger such intimacy might bring.

Gregory Scofield: The best metaphor that I can give is that it’s the scariest ride at a carnival. You wanna go on it, but you don’t wanna go on it. You buy tickets for it, and you walk around the entire carnival, doing all the other rides, eating, doing everything but going on that ride. So finally, it’s getting darker and it’s getting darker, and the lights have come up and the food smells are all around and you’ve got one ticket left. And it’s getting time to go home, but there’s that niggling feeling— I really really really wanna go on that ride.

So you look at this person that you’re with and you go, you know what? I think I’m ready, I think I wanna go on this ride. And so you’re waiting in line, the anticipation is building. You’re questioning yourself, “why am I doing this, should I be doing this,” yet at the same time, you’re really titillated. And you’re really filled with this anticipation and this ball in your stomach and you just don’t know what’s going to happen. The line moves. You and your friend are being ushered into one of the cars and the door is being locked. The gears are being revved up and you start to move. At that moment, you’ve completely yielded up your entire self. At this point, there is no going back. You cannot withdraw into yourself. You cannot get out. And even if you scream, they’re not going to stop anyway. In that split second, you’re thinking, “Oh my god, why did I do this? Why did I do this? What am I going to do?” And then at some point, you just absolutely let go, and say, “Well, I’m doing it.” And then the car starts to flip and you go upside down and the blood rushes to your head and you’re screaming and you’re laughing and you realize you do have a bar to hang on to and that at some point it’s going to be over and it’s okay and at some point very soon you will be upright again. At some point, it will stop and you’ll be on the ground, the arm will lift up, the door will open, you’ll stagger out of the cage, and you’ll be dizzy and you’ll be very grateful and so happy that you went on it. And then you’ll be ready to go home.

So, to me, that’s what that poem is like. In order to experience the absolute and utter jubilation of being turned upside down, you need to first of all say, “It’ll be okay, I think I can be turned upside down. I will be grounded again at some point.” But really what you’ve done is given yourself permission. You’ve allowed yourself to be vulnerable. And in allowing yourself that vulnerability, you’ve allowed yourself that experience. And allowing yourself that experience, you’ve allowed yourself all of the things that have come with that experience: the terror, the jubilation, the excitement, the panic. You’ve allowed yourself all of these amazing emotions, which once you’ve landed again permeate, they just radiate throughout your body and they become a part of your knowing.

SM: There are many poems in that same collection that linger over elements of the body in a way that remaps the body as a form of landscape. They claim the body in a way—they claim its beauty and they celebrate its beauty. At the same time, they bring in images that don’t tend to exist in poetry. They show the erotic potential of muskeg, of frogs, of slugs, of rocks. Are those two processes intertwined? Like the recognition of the landscape as significant, sacred, and sensual, and at the same time recognition of the body?

GS: They’re one and the same. One of the most amazing experiences I had while I was working on that particular book was working on a poem called “Ceremonies.” And I was sitting and I was writing, and I can’t tell you if it was late or if it was early or what the day was or what have you, but the image, the idea was—I was thinking about the sweatlodge, and I was thinking about the symbolism of sweating and its benefits and just how long it had been since I had actually gone to a sweat. And I was thinking about this, and the lines came to me, “My mouth, the lodge, you come to sweat.” And I thought, I can’t write that. I can’t write that because that’s taking a sacred ceremony and sexualizing it. And then I started to think… the sweat is a sacred purification. It’s the womb. It’s the womb of Mother Earth. You’re being born and you come out. And what I’m describing is just as much a ceremony, is just as sacred. “I heat the stones between your legs. My mouth, the lodge, you come to sweat.” That was the line. And that embodied, that one simple act, embodied an incredible ceremony. It embodied an incredible sacredness, and I took a stand on it and said, “This is sacred, and this is what Love Medicine, this is what these poems are about.”

And so what you’re saying about the land, about the ceremonies, about the things that come from that land, it’s all interconnected. The muskeg, the reeds, the rocks, the smell of the earth, the bogs, all of these things are medicines from the earth, and those are the things that we possess within our own bodies. We don’t have to look very far. Parts of our bodies are muskeg. Parts of our bodies, there are frogs there. And it was really just throwing those physical elements up and being able to give them to the spiritual energies where they exist. To me, people have oftentimes taken the spirit out of sex and sexuality. And if they haven’t entirely taken out the spirit of sex and sexuality, they’ve long since stopped looking to the ceremonies that accompany those things. When you think of these sacred ceremonies—of give-aways, naming ceremonies, fasting—sex and sexuality is all a part of that. You name things on someone’s body. You fast those things, you hunger them, you crave them, you sing those things, you dance those things, you taste those things, you feast them.

Gregory Scofield (Cree/Metis) is a poet, teacher, social worker, and youth worker whose maternal ancestry can be traced back five generations to the Red River Settlement and to Kinesota, Manitoba. He has published an autobiography, Thunder Through My Veins: Memories of a Metis Childhood (Harper Flamingo Press, 1999) and several books of poetry, including Native Canadiana: Songs from the Urban Rez (Polestar, 1996), Love Medicine and One Song / Sakihtowinmaskihkiy ekwa peyaknikamowin (Kegedonce Press, 2008), Singing Home the Bones (Polestar, 2005), and Louis: The Heretic Poems (Nightwood Editions, 2011).

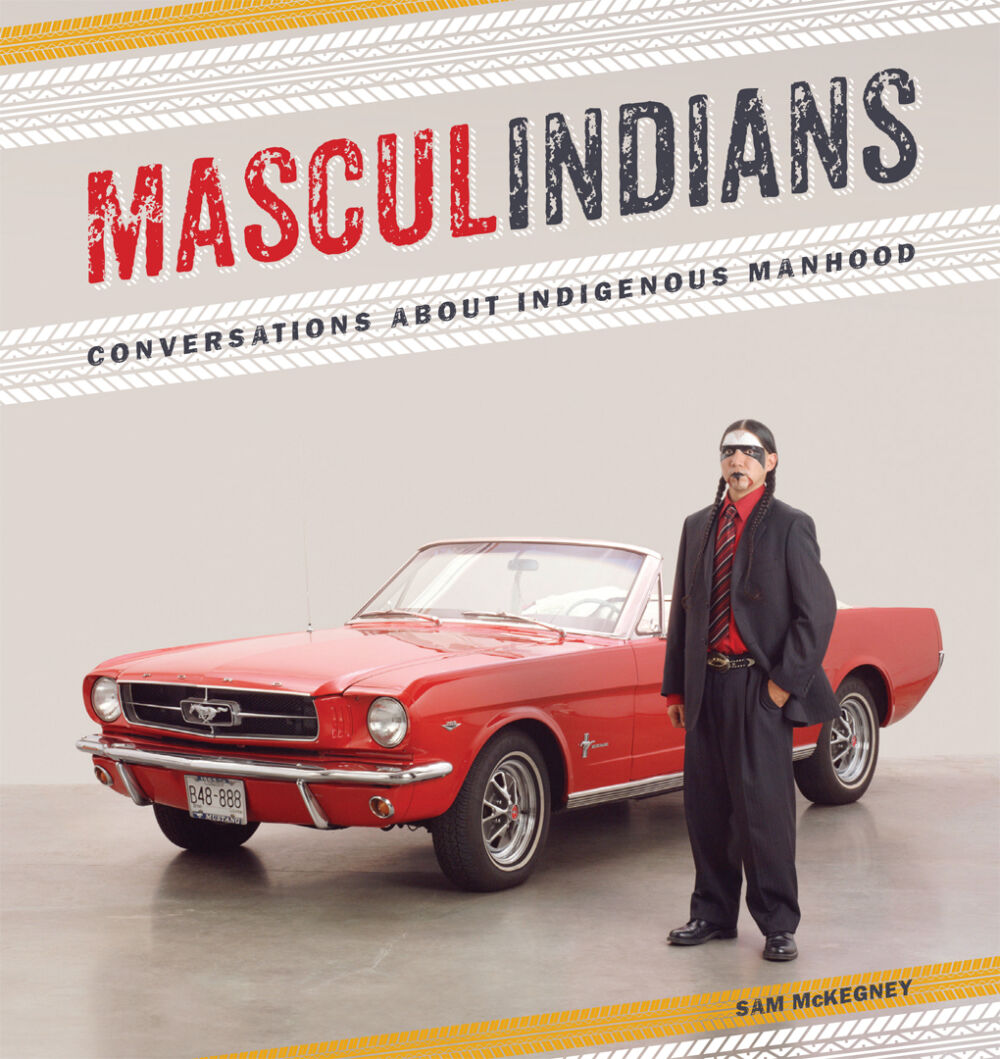

For more information on Masculindians: Conversations about Indigenous Manhood, click here.

Posted by Sam McKegney

February 6, 2014

Categorized as Excerpt

Tagged art, indigenous, literature, masculinity, men, poetry, women

Sanaaq in the Media Sam McKegney tours Masculindians