The following excerpt is from Adele Perry’s chapter of For a Better World: The Winnipeg General Strike & the Workers’ Revolt edited by James Naylor, Rhonda L. Hinther, and Jim Mochoruk (pages 39-60).

Shoal Lake water began running in Winnipeg taps in March of 1919, about six weeks before the General Strike began. The arrival of Shoal Lake water and the Winnipeg General Strike occurred at the same time and in the same place. In a number of ways, the events were mutually constitutive or, to put it another way, part of the same story.

[…]

Shoal Lake lies about 150 kilometres to the east of Winnipeg, on the western edge of the Lake of the Woods watershed. In 1913, the Indian agent reported that Shoal Lake 40’s members supported themselves by “trapping, hunting, fishing, working on steamers and in the lumber camps.” The building of Winnipeg’s aqueduct used Indigenous labour and knowledge and set into motion the dispossession of important parts of the modest amounts of lands and resources recognized as belonging to Shoal Lake 40. In the fall of 1913, the Greater Winnipeg Water District (GWWD) wrote to the federal government’s Department of Indian Affairs (DIA), requesting the right to build a camp and do survey work on the Shoal Lake 40 reserve. Ottawa readily agreed. At Shoal Lake 40, Chief Pete Redsky did what Indigenous people around Lake of the Woods had done for centuries: he worked to turn this into an opportunity for trade and for wage work. When Ottawa got wind that Redsky was selling sand and gravel to a contractor, they made clear that this could only be done if Shoal Lake 40 “surrendered” their rights to gravel and sand. A surrender process was conducted in December 1913, and Shoal Lake 40 lost its rights to these resources.

Photographic archives make clear the ways that Anishinaabeg men from Shoal Lake 40 worked in the early building of the aqueduct, documenting men clearing land around Falcon River and testing muck near the aqueduct’s intake. Questions of labour surfaced routinely in correspondence between the Indian agent, Ottawa officials, and Pete Redsky. As historian Mary Jane Logan McCallum explains, labour “was also part of a colonial apparatus meant to, among other things, extinguish Aboriginal title and status.” Amid the loss of their rights to resources and to land, Shoal Lake 40 was offered work. In late 1913 and early 1914 the contractor promised work to “all Indians wanting to work,” something that the agent thought “will be a great benefit to them.”

It was a particularly heavy aspect of Canada’s colonial law that would separate Shoal Lake 40 from critical parts of its reserve lands in the interests of Winnipeg’s water. They were not the only First Nation that lost reserve lands in these years. In the fifteen years between 1896 and 1911, a remarkable 21 percent of lands reserved for prairie First Nations were lost to the process of surrender and, as Sarah Carter has shown, surrenders picked up speed during the war. But by early 1914 it was clear that Shoal Lake 40 would lose the biggest and most significant and consequential part of its reserve lands through the particular mechanism of section 46 of the Indian Act. This section laid out a process by which reserve lands might be taken for “any railway, road, public work, or work designed for any public utility” without the consent or approval of the First Nation. In June of 1914 the City of Winnipeg paid the federal government $1,500 for approximately 3,000 acres of Shoal Lake 40’s reserve, representing three dollars an acre for 355 acres of land and fifteen cents an acre for lakebed and islands.

Chief Redsky would write, as he had before, requesting information and recompense for his community in the polite terms demanded in a colonial system that would, within a decade, formally ban First Nations from hiring lawyers or pursuing land claims. Late in December 1918, Redsky wrote to Ottawa: “This is asking the Government for the pay for the Reserve,” explaining that “the place was the best part of our Reserve,” land that was “very good Farming, Good timber, good hay land.” Redsky threatened to travel to Ottawa with an interpreter, and the local Indian agent tried to defuse the situation by promising “they could get all the satisfaction without his going down. The federal government would pay out the paltry amounts owed Shoal Lake 40 sometime after, but the reserve was still trisected by the land loss and the GWWD’s engineering works. Shoal Lake 40’s main settlement was relocated to what became a kind of artificial island. It remained as such until Freedom Road, a long fought-for twenty-four-kilometre gravel highway connecting Shoal Lake 40 with the TransCanada highway, opened in the spring of 2019, 100 years after Shoal Lake water began to flow in Winnipeg taps.

[…]

Beginning with the dispossession of Shoal Lake 40, the building of the Winnipeg aqueduct, and the General Strike allows us to see these complicated connections, and to register the Strike within an enduring history of settler colonialism. Organized labour, and the left, were tied to colonialism, to the active and regularly repeated exclusion of Indigenous peoples from the category of worker, and on the dispossession of Indigenous lands and resources. The Winnipeg General Strike did not challenge settler colonialism as much as it fought for a different version of it. Indigenous people were no more present in the radical visions of a possible Canada that emanated from soapboxes, printing houses, and shop floors in Winnipeg than they were in the boosters’ promises. In imagining a future without Indigenous people and without recognition of Indigenous territory and resources, the leaders of the Winnipeg General Strike accepted the core promise of settler colonialism as part of their wages of whiteness. An adequate history of the Strike and its enormous possibilities must also include recognition of this erasure, and what it meant for the social movements, scholars, and activists who have looked, and still look, to the Winnipeg General Strike.

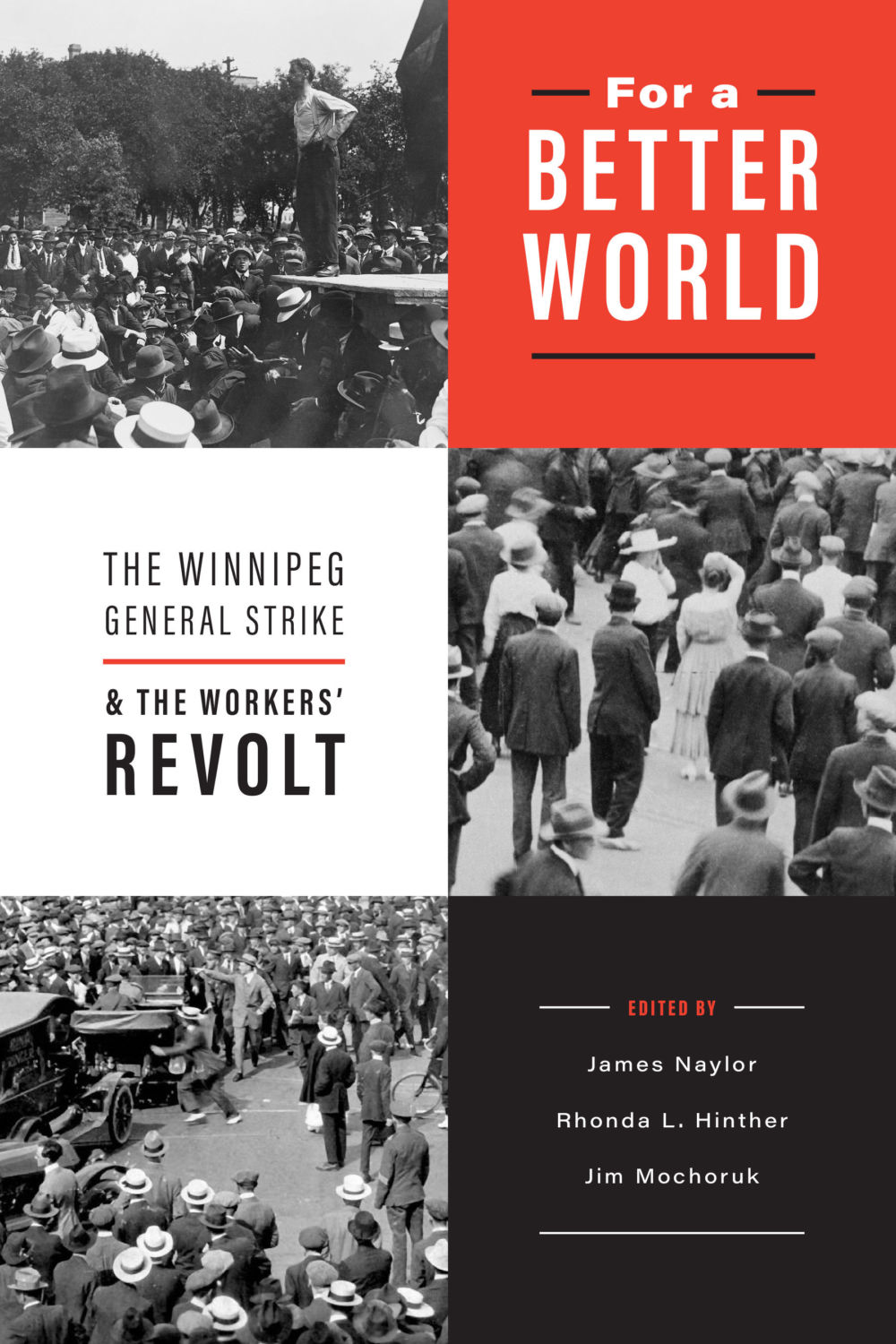

For a Better World

The Winnipeg General Strike and the Workers' Revolt

James Naylor (Editor), Rhonda L. Hinther (Editor), Jim Mochoruk (Editor)

Canada’s most famous example of class conflict, the Winnipeg General Strike, redefined conversations around class, politics, region, ethnicity, and gender. For a Better World interrogates types of commemoration, current legacies of the Strike, and its ongoing influence.

Posted by U of M Press

November 16, 2022

Categorized as Excerpt

Tagged for a better world, history, indigenous, labour, manitoba, shoal lake, winnipeg general strike

Now Available as Audiobooks! University of Manitoba Press is hiring a term Promotions Coordinator