An excerpt from the new English edition

of Inuit Stories of Being and Rebirth by Bernard Saladin d’Anglure

Between the Melville Peninsula and Baffin Island at the northern end of Hudson Bay and north of the Arctic Circle (69o 23´ N), lies a small island. It has fascinated many in the Western world since 1824, when a London publisher made available the narratives by Captain Parry (1824) and his second-in-command, Captain Lyon (1824), describing the two long years they spent looking for the mythical Northwest Passage to the Indies. The island is named Igloolik, literally, “the place where there are igloos.” Off its shores the two ships of the expedition, HMS Fury and HMS Hecla, cast anchor for the winter. Their names were given to the newly discovered strait northwest of the island.

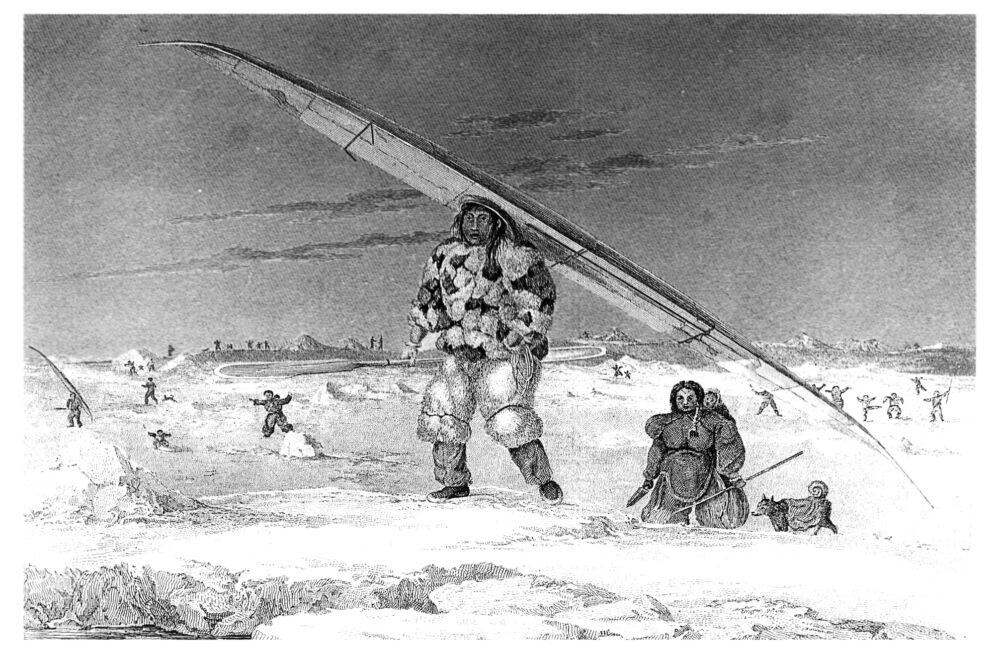

Both ships spent the winter of 1822–23 trapped in pack ice. At nearby Iglulik camp, officers and sailors alike got to know the local Inuit, then called Eskimos (Figures 4 and 5). Lyon even managed to learn enough of their language to talk with them, notably with their shamans. Thanks to this uncommon experience, Inuit customs were written up in two accounts that showed much empathy for this people, something very new at the time. Parry’s and Lyon’s narratives were a great success and were republished many times. It was the first time that this endearing people had been described with more emphasis on their humanity than on their strange customs.

One hundred and eighty years later, in May 2001, the Cannes Film Festival jury honoured the Iglulik Inuit by awarding one of them, Zacharias Kunuk, the Caméra d’or for his film A_tanarjuat: The Fast Runner_. In fact, the film had been conceived, written, produced, and performed collectively by the people of Igloolik through the efforts of three Inuit: scriptwriter Paul Apaaq, elder Paul Qulittalik, and director Zac Kunuk. Also helping was their friend and videomaker Norman Cohn. Together, they had formed a small production company, significantly named Isuma (reason), and created their first full-length film from one of the region’s great myths: the story of Atanaarjuat and his brother Aamarjuaq. The film was a hit on all continents, and Igloolik could now show millions of viewers its wondrous legends. Everyone acclaimed the profound humanity and courage of the Inuit (Saladin d’Anglure and Igloolik Isuma Productions 2002).

Meanwhile, in the wake of Parry and Lyon’s expedition, these distant islanders had also piqued the interest of science—in the person of the German Franz Boas, the founding father of American anthropology. He left Germany for Baffin Island in 1883 to study how Inuit relate to their environment. His first destination: a scientific station in Cumberland Sound that German researchers had used the previous year for the International Polar Year. Boas took Parry’s and Lyon’s narratives along with him in his luggage with the intention of going to Iglulik by dogsled. He also had travel accounts by the explorer Charles Francis Hall, who had gone to the same region between 1864 and 1869 to inquire about the 1847 disappearance of Rear Admiral Sir John Franklin’s naval expedition. Hall had inaugurated a new approach to travel, unusual for his time, of learning to live like Inuit and getting about by dogsled. This was the model that Franz Boas wanted to follow. Unfortunately, a severe outbreak of canine disease kept him from putting together a dog team for such a trip, and he had to make do with studying the Inuit of Cumberland Sound and neighbouring groups (Boas 1888).

Iglulik remained inaccessible to Boas. Eventually, through Captain George Comer, a famous American whaler, he managed to contact several of its inhabitants, who supplied him with ethnographic collections that are now kept at the American Museum of Natural History, in New York. Comer was based in New England and regularly went whaling in northwestern Hudson Bay. He also gathered myths and accounts for Boas about the region’s recent history and its inhabitants’ oral traditions. This material was published by Boas (1901, 1907), together with Baffin Island material that had been gathered for him by another whaler, Captain J. Mutch, and by Reverend Peck, an Anglican missionary stationed at Blacklead Island on Cumberland Sound (Boas 1888).

The project was taken up forty years later by Knud Rasmussen and the members of his Fifth Thule Expedition (1921–24). One hundred years after Parry and Lyon, Rasmussen, who could draw on all of his predecessors’ publications, chose the Iglulik Inuit to be the first destination of his expedition. Though not visiting Igloolik Island, he did meet many of its families and sent several of his assistants there. He had actually established his base camp on an island several hundred kilometres south of Iglulik, but not far from the winter dogsled trail running from that community southwest to the Repulse Bay trading post. Rasmussen complicated matters a bit by applying the term Iglulik to all Inuit in the huge territory from North Baffin (Pond Inlet and Arctic Bay) to the south of Repulse Bay. Later research by Dorais (2010 [1996]) has shown that linguistic and cultural differences justify classifying the inhabitants of the Repulse Bay region with another group: the Aivilik (“The walrus people”). Rasmussen eventually took his scientific expedition as far as the Bering Strait.

Rasmussen was the son of a Danish Lutheran pastor but spoke the Inuit language fluently, having learned it as a child in Greenland from his Inuit maternal grandmother. He thus had an edge over all of his predecessors and even most of his successors. Rasmussen’s major monograph, Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos (1929), became a must-read for anyone interested in the cosmology, shamanism, and oral traditions of Canadian Inuit.

Thus for the century stretching from Parry and Lyon to Rasmussen the Iglulik Inuit were seen as the quintessential Inuit group. Unknown to Westerners until 1821, they lived away from the sea lanes of Euro-Americans for several centuries in the marine cul-de-sac of Foxe Basin, which is often clogged by drifting pack ice in summer. There they remained beyond the reach of whalers, traders, and missionaries, unlike many other groups.

In 1931 the first white man, Father Étienne Bazin OMI, a French missionary, came to live among them in their winter camp at Avvajjaq, several kilometres from Igloolik Island, in a semi-subterranean Inuit house. Then in 1937, a Catholic mission was built on the island itself, on Ikpiarjuk Bay (“The little bag”), which offered better moorings than either Avvajjaq or the old Iglulik winter camp. Two years later it was the turn of the Hudson’s Bay Company to build a store, not far from the mission (Laugrand 2002).

In 1959 an Anglican mission was erected a bit farther away and an Inuit minister placed in charge. That same year saw the arrival of the Canadian government’s first administrator, and with him several civil servants who set out to develop the infrastructure of an organized village.

The people were still living in traditional seasonal camps, while regularly coming to Ikpiarjuk for trade and religious services. Then the first pupils were sent to the Catholic boarding school in Chesterfield Inlet, and several families came to live in the village and do the first service jobs. Others left to live near the U.S. Army radar station at Hall Beach, around fifty kilometres south of Igloolik Island, where many job opportunities were available.

From then on, the Inuit became more and more sedentary. A school was built in the village, then a nursing station and a police station, and finally a co-op store. The site previously known as Ikpiarjuk was officially renamed Igloolik and given an elected municipal council. In 1966 there were already fifty or so little prefab houses, followed later by the same number of new multi-room family homes. By the late 1960s only a few families were still spending winter in camps, living either in semi-subterranean homes of sod, stones, and hides or in igloos of snow. Most igloos were now temporary shelters for hunting or for visits to other villages.

I witnessed similar changes in Arctic Quebec between 1955 and 1970. In 1956 most families were still living in snow igloos; five years later they had to move to Euro-Canadian settlements for compulsory schooling of their children. This settlement policy entailed the rapid abandonment of snow igloos, kayaks, dogsleds, and a diet based mainly on local resources.

In 1971, when I first came to the village of Igloolik, I intended to complete the study I had been conducting for nearly six months in Arctic Quebec (present-day Nunavik) on the way Inuit imagine the reproduction of life, on the customs surrounding the socialization of their children, and on the beliefs, rules, and myths that explain, uphold, or justify those customs. My plan was to spend December in Igloolik gathering comparable data on these themes. I already knew the Tarramiut Inuit dialect, which the people of Igloolik easily understood although it differed slightly from their own. An Inuit assistant, Jimmy Innaarulik Mark from Ivujivik, Nunavik, accompanied me. He had worked with me for two years and had assisted me in developing my research project, using previously gathered data, and in transcribing recorded interviews into standard written form.

Two researchers had come to the area several years before. The first, David Damas, an anthropologist, spent a year (1959–60) examining the kinship and residential patterns of Inuit camps (Damas 1971). The second, Jean Malaurie, a geographer, spent several months in the region in 1960 and 1961 studying the ecology of hunting among local families and their micro-economic structures (Malaurie 2001). Both had learned some rudiments of the Inuit language but could not speak it well enough to conduct interviews without an interpreter.

Upon my arrival in Igloolik, I visited the local Anglican minister, Reverend Noah Nasuk, an Inuk native to the region. He received me very simply, and to my question about which elders could best help me in my research he unhesitatingly referred me to his uncle Ujarak and his female cousin Iqallijuq. The first elder, an Anglican convert, was around seventy years old, and the second, a baptized Catholic, several years younger. I went to visit each of them, and they agreed to come and work with me the next day. To avoid any misunderstanding due to differences in dialect I hired another assistant: a young local Catholic girl, Bernadette Imaruittuq, who had gone to the boarding school in Igluligaarjuk (Chesterfield Inlet).

The two elders’ names were not unknown to me, but I could not remember where I had seen them. I looked up the population list that Rasmussen’s team had made in 1922 and found the names there: Ujarak, the son of the great shaman Ava; and Iqallijuq, his girlfriend. They had been living together in the shaman’s igloo where Rasmussen had spent several days. Surely they had been the namesakes of my two future assistants, who now lived in separate homes at one end of the village. At the appointed time the next morning, I greeted them and offered tea. To lighten the mood I smiled and mentioned that fifty years earlier a man called Ujarak had lived in Iglulik with his girlfriend Iqallijuq. Were they named after those two? They looked at me with surprise and, laughing, told me: “That was us. We were young back then!” Before me were two witnesses to Knud Rasmussen’s visit. And what witnesses! They had lived in the same igloo as the Danish explorer and had attended his discussions with Ujarak_’s father—the shaman _Ava_—and his mother, _Urulu, herself a shaman.

This unforeseen meeting turned all of my plans upside down. Both elders would be remarkable informants. They had spent most of their lives in the camps and fully remembered the pre-Christian period. They soon became my friends and my teachers of Inuit culture and history. Until _Ujarak_’s death in 1985 and _Iqallijuq_’s in 2000, I would work with them and their families to gather the oral traditions of their people—a period totalling thirty years. The quality of their accounts, which differed from and complemented each other, especially on the subject of shamanism, justified suspending all of my other research projects in Nunavik, where I returned only after their deaths. Even then, I still kept in touch with my many Igloolik friends, who since 1998 have taken an active part in producing films about their history and culture. It is at their request that I have dusted off the abundant material I accumulated over the past thirty years about their oral tradition, in order to make it available to them and to a broader audience. One outcome is this book.

Posted by U of M Press

December 3, 2018

Categorized as Excerpt, Related Reading

Tagged art, books, community, culture, elders, environment, franz boas, gender, history, igloolik, inuit, iqallijuq, knud rasmussen, northern, nunavut, shamanism, the third sex, ujarak

Mapping Rooster Town Back In Holidays + Books!