The following excerpt is from Kahente Horn-Miller’s chapter of Indigenous Celebrity: Entanglements with Fame edited by Jennifer Adese and Robert Alexander Innes (pages 80-104).

The media tried to set me up as a media plaything, inviting me to publicity occasions. As an onkwe-hon-weh I was uncomfortable standing out from the crowd and being looked at as an object.

—kahntinetha Horn

The public life of kahntinetha Horn has been largely shaped by the camera lens and reporters’ pens. In the early 1960s, she modelled fashion for print and then the runway in Montreal, Toronto, and New York City, garnering attention as a rare Indigenous face in an industry populated by whiteness. She turned this early attention into activism that had been fuelled years earlier by the destruction of her grandparents’ home on the Caughnawaga Indian Reserve after the expropriation of their land for the St. Lawrence Seaway. kahntinetha became the Indian Princess of the Indigenous and Canadian imaginations. She just might be one of the first modern-day Indigenous celebrities.

[…]

My mother was born at Queens County Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, on 14 April 1940. She is the second oldest of nine children. Her father, Joe Horn, was an ironworker, and her mother, Margaret Diabo, was a homemaker. Her father died when she was thirteen in a work-related accident, slipping and falling off a bridge in Vermont. kahntinetha also has a half-brother around the same age who entered her life as an adult. Her formative years were spent living with her mother’s parents on their farm near the St. Lawrence River. She grew up with some of her siblings hearing and speaking the old Mohawk language and being exposed to the longhouse traditions. It was in the Indigenous tradition of visiting and sharing food that our mother would have been exposed to many conversations among Elders about our history, culture, and traditions in the Mohawk language around a wood stove late into the evening. This tradition would later inform her activism.

[…]

Our mother has used and continues to use a mixture of letter writing, public speaking, marching on front lines, supporting blockades, and showing physicality to engage in activism. She came of age in a time when one’s Indigenous identity arose from being an active participant in the movement rather than from proficiency with the Mohawk language or involvement in ceremonial life. You were Indian if you had braids, wore fringe, fought hard, spoke out, rallied, and tuned in. While at a funeral in Akwesasne of a cousin and activist who had worked alongside my mother, I had the opportunity to witness how people of her generation viewed her and how they engaged with her at that event. The three women and the one man who stood talking with her had participated in the Cornwall Bridge Blockade in 1969 and reminisced with her about old times, laughing and chortling over their actions of over fifty years ago. One woman said twice that our mother had taught them that they had to stand up and fight back: “She taught us to stand on our own two feet.” Our mother had taken the air out of car tires with a small camera tool as an act of resistance.

[…]

A famous story of her particular brand of activism is about when our mother let rats loose in Indian Affairs. It is documented in The Canadian Encyclopedia, and I remember reading it many years ago. We asked her about it, and she told us the story. It has stayed with me, and I have shared it with my own daughters to illustrate their grandmother’s character. They were not surprised but entertained. The way that she tells it is that the City of Montreal was dumping its garbage on the Caughnawaga Reserve, and the community couldn’t stop it. As a result, many homes were infested with rats. It was when she encountered rats in her home that she decided to take action.

At a speech given at the old Indian Affairs building in downtown Ottawa, she lifted a dead rat by the tail above her head as she made her point. There were also live rats in the box in front of her, and they became excited. As they moved around, the box fell from the podium, and the rats escaped. This was the 1970s, and bell bottoms were in style, so you can just imagine the reaction of the audience. Many men and women jumped up on their chairs in fright. They did not want the rats climbing up their wide-legged pants or skirts. Her aunties and cousins who had accompanied her sat stoically in the audience and did not move. It was not until they left the building and went around the corner that they began to laugh and laugh. Her aunt Francis liked to tell this story. Our mother says that they had to fumigate the entire building afterward. She had made her point. The dumping eventually ceased. It was this kind of activism that made her popular among other Indians. No one else was doing this kind of thing. Infusing humour into her serious statements on the affairs of our people seemed to make for effective change.

[…]

The importance of the role of kahntinetha’s beauty in her celebrity lies in the fact that her beauty is the first thing to be referenced followed by her words by those who remember her activism of the 1960s, much like the reporters of the time. kahntinetha is fondly remembered as the outspoken and militant Indian Princess. I propose that this identity goes beyond mere objectification and is tied directly to what she sees as her responsibilities as a Mohawk. It is important as we examine kahntinetha in the context of Indigenous celebrity, different from non-Indigenous celebrity. This difference was outlined briefly by Waneek and Kaniehtiio as we discussed our mother. Both of my sisters have extensive experience with this issue and can speak to it with knowledge. Indigenous celebrities, they agreed, are held accountable to their communities of people, whereas non-Indigenous celebrities seem to be able to leave the places in which they grew up, severing all ties. As we spoke further, they said that when our mother spoke or acted, she always did so with the idea in mind that she was accountable to her community, Kahnawake, and the Mohawk Nation at large. Our women are beautiful, and our people are strong. This was the image that she wanted to project to her audiences.

[…]

Pocahontas, to her credit, is probably one of the most recognizable Indigenous women, and it is through her story that we can find links to the celebrity status of kahntinetha. The life of Pocahontas is the tale of colonization itself—her invasion, her subordination, her socialization, and her total subjugation. She is the Indian Princess of the North American imagination. Pocahontas serves as the ideal stereotype of the Indigenous woman as the “promiscuous female body, as fecund and wild and seductive as the land,” whereas kahntinetha, by her activism and outright refusal to be what was expected, pushed back against the system, in essence saying that this is who I am, this is who you are, and these are my rights. Whereas Pocahontas could not speak back, kahntinetha used television, print, and radio to fight colonization and its impacts.

She came of age during the emergence of the Red Power movement and the Sexual Revolution, and this influenced her view of the world and fuelled her activism. kahntinetha unabashedly addressed Canadian leaders and intellectuals with a speech, a shout, or a letter to the editor. One only has to look at the many photographs of her talking to Canadian politicians to see how she addressed them and the issues head on. In them, she stands close, almost face to face, projecting her words into their faces so that they could not ignore them. Canadians didn’t know what to make of her because she did not match the stereotypes that most had been socialized to—she was Indigenous, beautiful, smart, vocal, and could throw a good punch.

[…]

In the context of the 1960s, we can view kahntinetha’s celebrity from the perspective of settler colonial desire, though Indigenous men were caught up in such desire too. Is this idea of desire about sexualizing Indigenous bodies, as Robertson, Green, and Bell propose? How can we take that back? The way that kahntinetha functioned with complete knowledge of the desire that people have had for her decentralizes the notion of Pocahontas as victim and actually puts her in a place of power. Were Pocahontas able to meet her, I think that they would have a lot to talk about.

From a young age, my mother understood the context in which she was living. She had full mastery of the tools at her disposal. She could think. She could write. She could punch. What more do you need? She also knew that she was coming from a strong grounding in the language, culture, and history of her people. She was never a naive and manipulated figure, and at times she was rash, obnoxious, and violent. That is why she is such a controversial figure. She was never an Indian Princess.

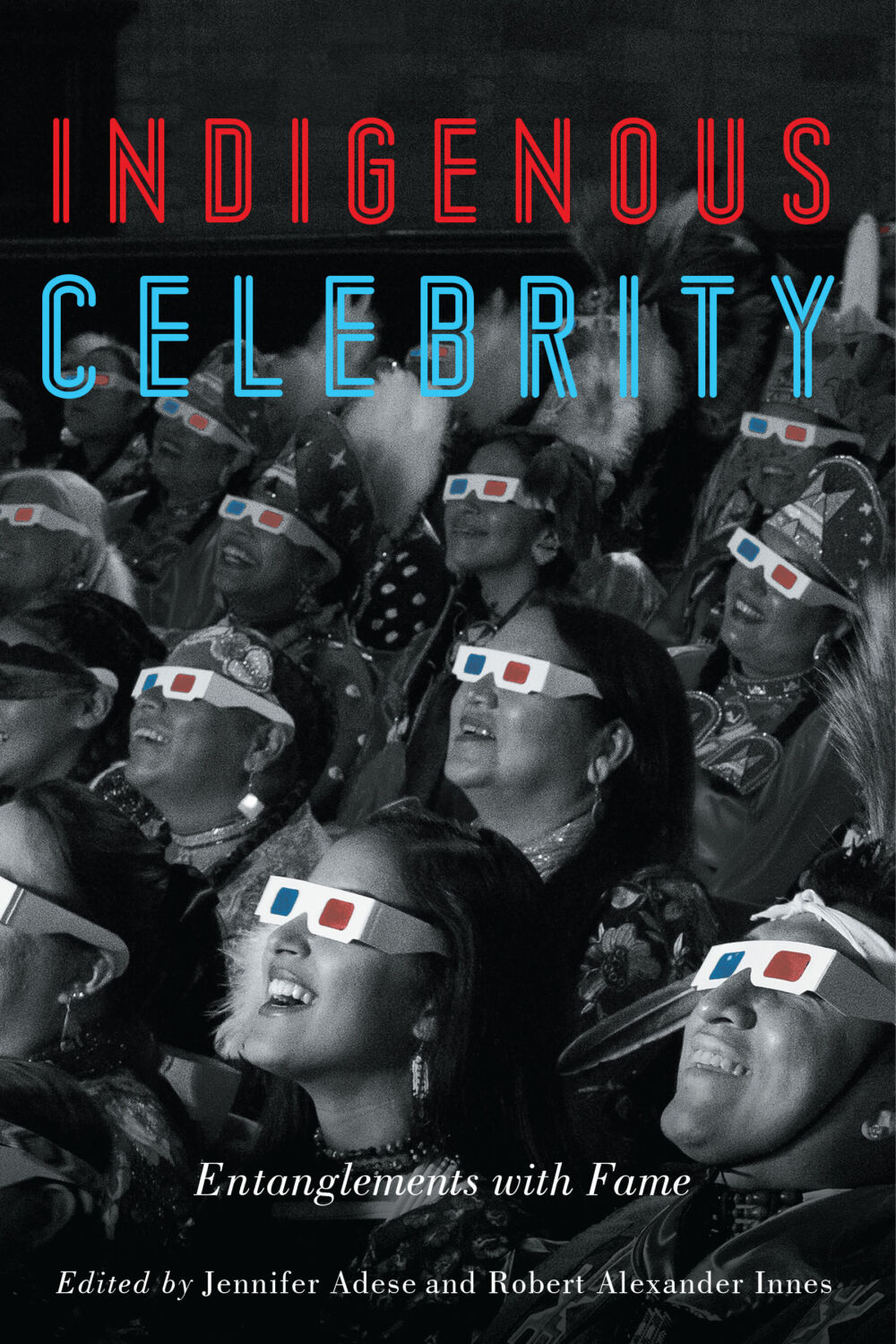

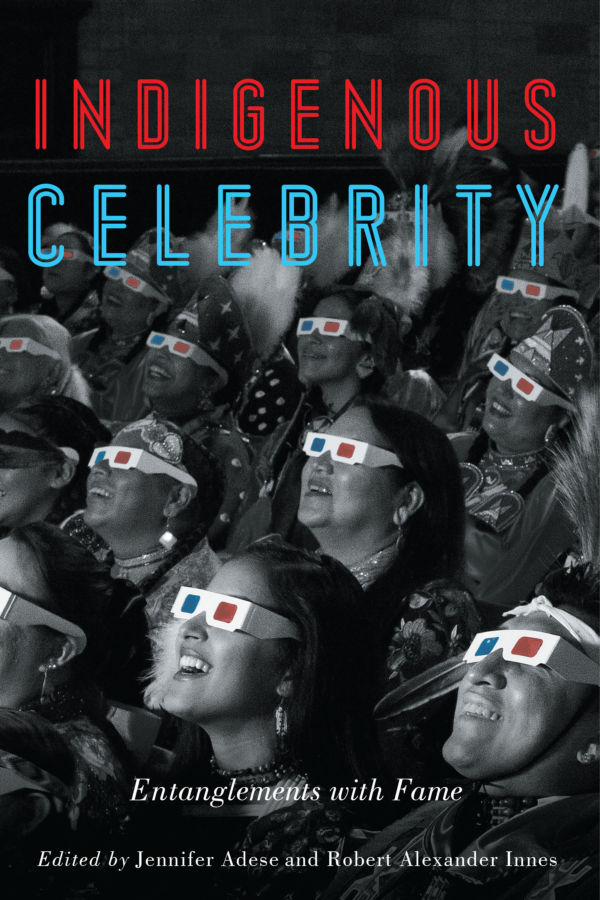

Indigenous Celebrity

Entanglements with Fame

Jennifer Adese (Editor), Robert Alexander Innes (Editor)

Indigenous Celebrity speaks to the popular forms of recognition, critically recasting the lens through which we understand Indigenous people’s entanglements with celebrity. A wide range of essays explore the theoretical, material, social, cultural, and political impacts of celebrity on and for Indigenous people.

Posted by U of M Press

April 11, 2022

Categorized as Excerpt

Tagged community, identity, indigenous, indigenous celebrity

In Memoriam Indigenous Celebrity: Excerpt on the boxing match between Justin Trudeau and Patrick Brazeau