The following excerpt is from Kim Anderson and Brendan Hokowhitu’s chapter of Indigenous Celebrity: Entanglements with Fame edited by Jennifer Adese and Robert Alexander Innes (pages 146-162).

The fight begins with Justin Trudeau, son of one of Canada’s most notable prime ministers, Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Trudeau-the-father held office from 1968 to 1979 and again from 1980 to 1984, a figure both loved and hated by the Canadian population. As much as Canadian prime ministers become “celebrities,” he was noted for his bold “just watch me” attitude along with his intellect. Among Indigenous peoples, Trudeau-the-father is also remembered as the prime minister who commissioned the 1969 White Paper, a policy proposal aimed at bringing about total and final assimilation of Indigenous peoples into whitestream Canada, under the guise of equality but at the cost of eliminating Indigenous rights. It was one more attempt to reckon with Canada’s “Indian problem”: that is, Indigenous peoples who held fast to their cultures and rights.

[…]

In 2012, when this story takes place, Trudeau was serving as the Member of Parliament for the riding of Papineau in Montreal, but he was on the rise to become leader of the Liberal Party of Canada and later the second youngest prime minister in Canadian history. After becoming prime minister in 2015, he received international adulation because of his youth and charismatic good looks as well as his gentlemanly comportment and self-declared feminist positioning. But the path to leadership for Justin Trudeau wasn’t without challenges, and the one of interest to us concerns his masculinity.

During his campaign to become leader of the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party of Canada issued attack ads calling his masculinity into question. In one, Trudeau is surrounded by fairy dust, swirling stars, and text that reads “bungee jumping coach; [d]rama teacher for two years,” and “when it comes to Canada’s economy, Justin Trudeau just isn’t ready.” That slogan— he “just isn’t ready”—became a primary tool that the Conservatives would employ. Because of the campaign to discredit him according to these gendered tropes of leadership, Trudeau needed an image makeover that would position him as a strong leader, ready to take charge. Someone on his team must have decided that using a farcical, blatant device such as a fight would help with this image. So they staged a celebrity boxing match, a “Fight for the Cure” (for cancer), that would take place in March 2012.

The team needed an adversary for the fight, and they found one in Patrick Brazeau, an Indigenous senator affiliated with the Conservative Party. In an interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Trudeau was quoted as saying that “I wanted someone who would be a good foil, and we stumbled upon the scrappy tough-guy senator from an Indigenous community. He fit the bill, and it was a very nice counterpoint.” Trudeau later expressed regret about making this comment, stating that it was not in keeping with Liberal Party discourse of Indigenous-settler reconciliation. Brazeau, however, did not hesitate to fulfill his role as the perfect villain for Trudeau. An Algonquin man from the community of Kitigan Zibi, Brazeau grew up not far from the nation’s capital but under obviously different circumstances in terms of race and class privilege. As a lesser-known public figure, Brazeau had served in Indigenous politics as the president of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples. Toward the end of his tenure, his leadership came under fire with allegations of creating a culture of sexual harassment and heavy drinking, but he moved from this position into the Senate, where, at the age of thirty-four, he was appointed to a lifetime seat by Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper. Trudeau was well on his way to becoming the leader of the country, but Brazeau would soon find himself mired in further controversy after insulting Indigenous and settler women with misogynistic tweets and later facing charges of cocaine possession and sexual assault and a suspension for investigation of fraud in the “Senate scandal.” He was later acquitted of charges related to the Senate and pleaded guilty to charges of cocaine possession and simple assault.

[…]

Posters for the event promoted “The Thrill on the Hill” between “Justin ‘Pretty Boy’ Trudeau” and “Patrick ‘Ponytail’ Brazeau.” The question of masculinity was central since there were references to Trudeau as the “shiny pony” by Conservative commentator Ezra Levant and online comments calling his masculinity into question: “Brazeau should knock him out if it is a real fight and send ‘Justine’ back to the comforting arms of his wife who can twirl her fingers through his metrosexual locks.” Brazeau, nicknamed the “Senator Soldier,” indulged in pre-fight banter that included “dick jokes”: “I’ve got a lot of length over here,” he said to Trudeau at the weigh-in while pulling out the waistband of his bikini briefs and looking down.

The media played with the “savagery” of Brazeau, at best making him out to be a Harlequin book cover brave—“his hair is unponytailed, long and flowing, full of power and eroticism”—but more often playing into one of the prime tropes of Indigenous men: the bloodthirsty warrior. Trudeau joined in creating the savagery of Brazeau. In response to pre-fight social media banter between the two, Trudeau tweeted “are you ok, Pat? That’s even more unintelligible than usual. Stick to your usual grunting and snarling.” As for the fight itself—it was anticlimactic, lasting only a few minutes. Trudeau won. The press delighted in photos of Trudeau taking a victory kiss from his wife, clad in a tight black dress fitting for a ringside groupie.

[…]

In the days that followed the fight, there was a lot of banter about how “classy” Trudeau was, countered by calling attention to the brutish behaviour of Brazeau. In honour of the victorious Trudeau, one of the Liberal Members of Parliament recited a poem in the House of Commons in the style of Robert Service—a late-nineteenth-century and early-twentieth-century Canadian poet—much celebrated for his ballads on the frontier hero. Whether deliberate or not, the boxing match thus helped to bolster Trudeau’s masculinity, a necessary ingredient in his being perceived as “prime ministerial.”

[…]

In relation to the celebrity boxing match, Trudeau literally fought to demonstrate that, though he might be a feminist, he also had the classically masculine traits of fortitude, stamina, and guile typically associated with pugilism. The end game for Trudeau was not to beat Brazeau but to demonstrate his white heteromasculinity to be as virulent as his father’s and to show corporeal control.

[…]

For Trudeau to produce such a stoic, self-restrained, and measured fight plan spoke to his will to align himself with a constructed heroic morality that lies at the core of white heteropatriarchy: the rational achievement of mind over body. In contrast, Brazeau was lambasted for his poor discipline while heavily underscoring his own narrative via exotic and highly sexualized motifs.

Fighting has its own specific genealogy—at least partly linked to land ownership—that, in the context of unsettler colonialism, speaks volumes to the import of this celebrity event. “Gentry masculinity,” as analyzed by Raewyn Connell, was a class of hereditary landowners “who dominated the North Atlantic world of the eighteenth century” based on land ownership and an emerging capitalism: “The gentry provided army and navy officers, and often recruited the rank and file themselves. At the intersection between this direct involvement in violence and the ethic of family honour was the institution of the duel. Willingness to face an opponent in a potential lethal one-to-one combat was a key test of gentry masculinity, and it was affronts to honour that provoked such confrontations.” Reading this celebrity bout in light of Connell’s historical analysis of gentry masculinity elucidates what was at stake for Trudeau at least: gentlemanly reputation and the defence of his father’s White Paper.

[…]

The celebrity boxing match, pitting the Indigenous man against the unsettler man, far from being an event signifying Indigenous resistance, was an event of complicity. As Beynon points out, since “fighting has long been a culturally sanctioned and distinctively male way of conflict resolution, in this respect, violent men can be viewed as over-conformists,” yet Brazeau’s conformity also served to disrupt colonial discourse. This brief genealogical contextualization of this celebrity pugilist bout reveals the stakes of the fight: the upholding of a particular form of morality underpinned by manly virtues, repressive of feminine qualities, tied to the ongoing suppression through violence of Indigenous land rights, and generally the apprehension that unsettler cultures have regarding Indigenous masculinity.

[…]

The dominant discourse, at least, certainly reinforces the fragility of Indigenous masculinity as produced via the prevalence of violence, drug and alcohol abuse, heightened sexuality and physical and sexual abuse, and spousal abuse. Connell explains that this “protest masculinity” arises from an experience of powerlessness and leads to an exaggerated claim to the gendered position of masculine power. In many ways, Brazeau was the poster child for such an analysis, his well-documented misogyny serving simultaneously to reinforce the “savage” trope and, in this particular celebrity event, to give allegorical credence to Trudeau’s claims to gentry masculinity. The predictable outcome of the fight, then, reinforced what dominant colonial discourses are founded on—the immorality of the Native man and the morality of the Western man.

[…]

This question could rightfully be asked: “What if Brazeau had won, wouldn’t that have reaffirmed Indigenous rights?” Our answer would be “no.” All celebrity events involving Indigenous peoples must always be read via a colonial genealogical method (i.e., the production of Indigenous bodies through discourse), so in this case winning or losing the fight was unimportant. Many representations of Indigenous peoples are inherently violent because they are produced by a system underpinned by an apparatus designed to subjugate Indianness regardless of the outcome. Brazeau’s loss, in simple terms, represented another victory for colonial white masculinity over the less evolved and self-restrained “savage.” If Brazeau had won, however, then the sight of a frenzied Indian pummelling a skinny white guy would have played into the trope of the “ignoble savage,” reaffirming the colonial state’s right to control the violence of the “savage.” This celebrity boxing match reminds us that the creation of the discourse of the “Indian problem” was never about resolving the issue; it was always about Indian presence being “the problem.”

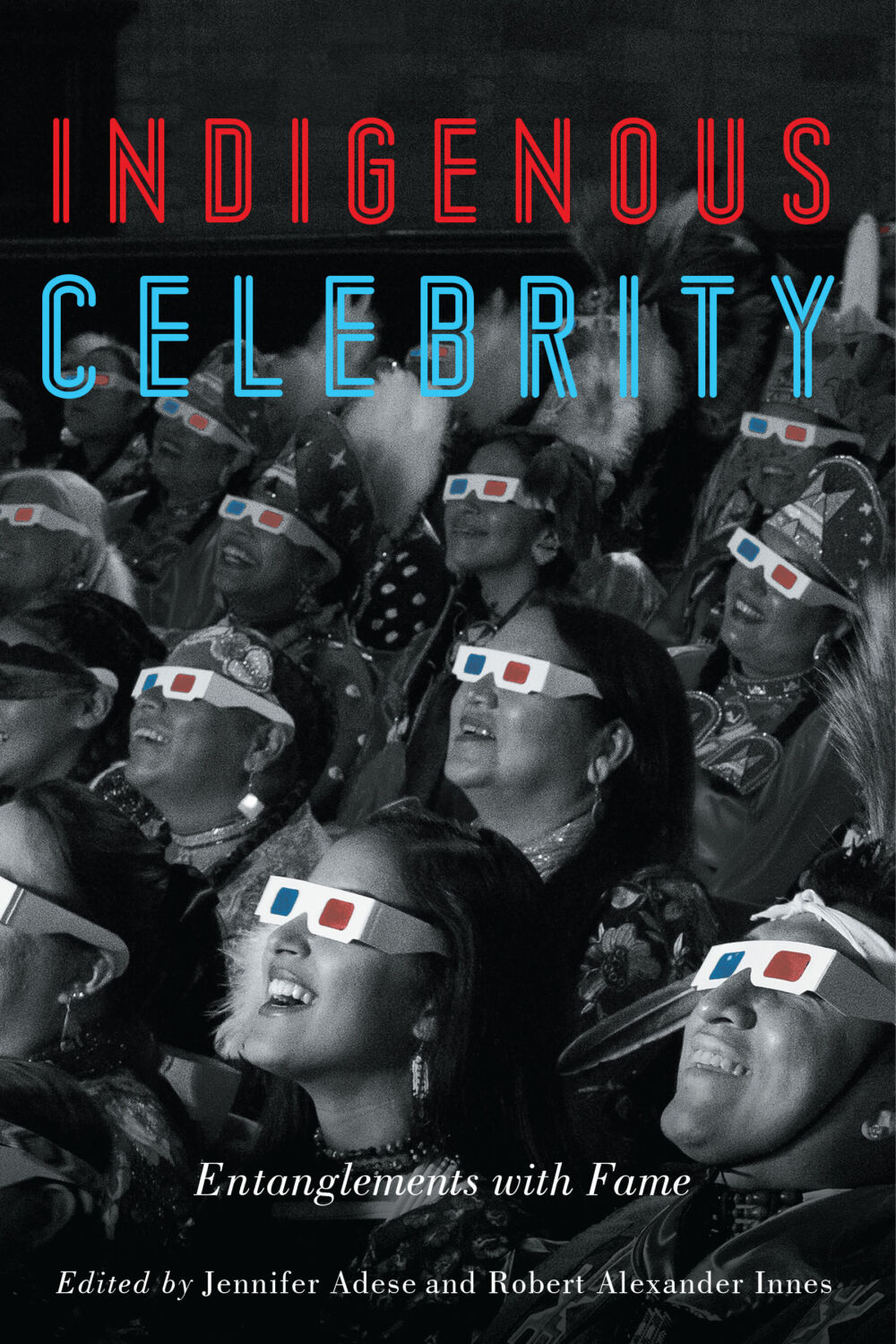

Indigenous Celebrity

Entanglements with Fame

Jennifer Adese (Editor), Robert Alexander Innes (Editor)

Indigenous Celebrity speaks to the popular forms of recognition, critically recasting the lens through which we understand Indigenous people’s entanglements with celebrity. A wide range of essays explore the theoretical, material, social, cultural, and political impacts of celebrity on and for Indigenous people.

Posted by U of M Press

April 18, 2022

Categorized as Excerpt

Tagged identity, indigenous, indigenous celebrity, trudeau

Indigenous Celebrity: Excerpt on “Military Mohawk Princess” kahntinetha Horn Celebrating Canadian Independent Bookstore Day 2022