Nathan Hatton’s Thrashing Seasons: Sporting Culture in Manitoba and the Genesis of Prairie Wrestling was published by the University of Manitoba Press in 2016.

Thrashing Seasons tells the story of wrestling in Manitoba from its earliest documented origins in the eighteenth century, to the Great Depression. In addition to chronicling the colourful exploits of the many athletes who shaped wrestling’s early years, Hatton explores wrestling as a social phenomenon intimately bound up with debates around respectability, ethnicity, race, class, and idealized conceptions of masculinity. It provides an exceptional lens through which Manitoba’s 150 years, and proceeding years, can be viewed.

Nathan Hatton grew up in the communities of Prairie River, Saskatchewan, and White River, Ontario. He teaches history at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay. In addition to his academic pursuits, Dr. Hatton coaches submission grappling and Brazilian Jiu Jitsu.

*

Professional Wrestling’s Early Years in Manitoba

Among the large male population, interest in individual tests of physical strength and skill ran high, and it is little surprise that wrestling, which the press was already covering in detail by the early 1880s, became popular among Winnipeg’s young men. As Morris Mott notes, virtually any organized sport in Manitoba can trace its origins to Winnipeg. Wrestling is no exception. Although impromptu wrestling matches undoubtedly took place throughout the city, by the early 1880s local commercial entrepreneurs began to capitalize on the sport’s popularity.

During this period, a relationship was established that would remain important well into the twentieth century: organized wrestling maintained close ties to Winnipeg’s hotels and liquor establishments. As noted, this connection had existed for years in the taverns of Great Britain, Ontario, and the eastern United States, and like many customs it was recreated by settlers in the west.

In the spring of 1882, Winnipeg’s first known wrestling gym, one of many that would spring briefly into existence over the next four decades, opened at the Winnipeg Hotel when two individuals named Barnes and Tilley began offering instruction in the sport to the public along with sparring and club swinging.

Thomas Montgomery, proprietor of the Winnipeg Hotel, evidently took an active interest in the sport himself and was not reluctant to demonstrate his skills in his own establishment. In 1884, while engaged in a “friendly” bout in the hotel’s bar, he accidentally injured Mr. Nott, co-proprietor of a local plumbing, steam, and gas fitting firm. Nott fractured his leg when he was thrown awkwardly to the ground, requiring a surgeon’s attention to set the bone.

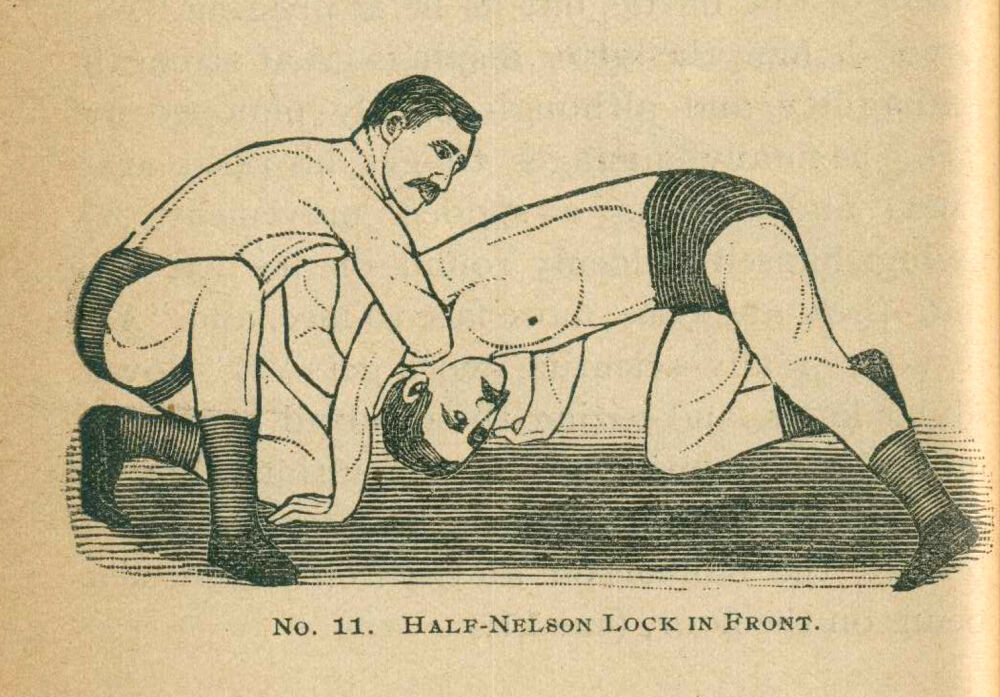

Although wrestling invited potential injury, the risk of physical harm did not, by itself, generate controversy for the sport. Indeed, among middle-class reformers, wrestling had the potential to inculcate many desirable traits, and contemporary accounts frequently spoke of its benefits. Among young boys, wrestling was encouraged as a positive, “natural” activity that exercised all of the body’s muscles.

Some commentators even advocated it for men in their advanced years, stating that “two old men living in a city can get excellent exercise by wrestling in a large, light room,” but of course, because of their age, “there must be more gentleness displayed in the struggle than two 12 year old boys would observe.”

Even more important was its efficacy as a character builder for young men. Part of wrestling’s perceived value was its effectiveness in combatting effeminacy. Wrestling, along with other combative sports, could help a boy to avoid a reputation as a “milksop” or “sissy” among his peers.

By the late nineteenth century, effeminate behaviour carried the potential for social scorn among one’s age cohort, but it was also viewed as a moral failing in its own right. The soft, weak body became indicative of a soft, weak character. With little physical capital, the effeminate man might resort to more devious means to achieve goals.

Physical training, particularly in combative sports, offered an antidote to effeminacy that could also teach boys to stand up for themselves in an honourable and respectful fashion—a habit that would be of benefit to future businessmen.

As Judge Henry A. Shute opined, “let your boys learn to box, to wrestle, to fence, and so develop every muscle. I never yet saw a boy who knew how to box strike with a club, a stone or a dangerous weapon.”

Although a safer and more morally uplifting alternative to solving personal disputes with weapons, wrestling injuries did occur. Yet injuries occurred in many sports. Playing rugby, for example, which assisted in developing so many of Tom Brown’s “manly attributes” and was the conscious creation of middle-class British educators, commonly resulted in injuries and even deaths.

Such tragedies were tolerated, if never fully accepted, because of the moral qualities that aggressive sports imbued in their participants.

With regard to wrestling, of greatest concern to middle-class reformers was not its danger but the fact that matches were generally associated with less reputable activities such as gambling, rowdy behaviour, and alcohol consumption. Individuals prominently involved in the sport also constituted less “respectable” members of society whose behaviour was not in keeping with the tenets of Muscular Christianity.

Additionally, many of the wrestling matches held in the province were not seen to serve “higher” purposes.

Newspapers sporadically reported the problems associated with professional wrestling. On 22 March 1882, for instance, the Manitoba Free Press carried a report from Pueblo, Colorado, of a match at a local theatre in which a defeated wrestler’s supporters threatened the referee with pistols. A general fight erupted among the spectators, resulting in one man being rendered unconscious and another being injured severely.

Such reports contributed to wrestling’s growing reputation as a dubious commercial undertaking, and local newspapers occasionally took on the role of moral guardian for the community.

The Winnipeg Sun, in commenting on British-born wrestlers Duncan C. Ross and Edwin Bibby, warned that “if Winnipeg is ever threatened with an eruption of this fraternity the Sun will light up some of the dark corners of these contests.

The Sun man has been there.” With the growing population of young men and the subsequent proliferation of other “less respectable” entertainments, however, wrestling became one of the many commercial amusements offered in the city. By early 1884, the sport, along with boxing, was evidently popular among Winnipeg’s residents, and matches were being staged in the various variety theatres that had been quickly erected to meet growing demands for entertainment.

In April 1884, the Winnipeg Sun, reporting on a recent boxing match at the Theatre Comique, noted that “pugilistic encounters and wrestling matches are the latest dodges resorted to by the proprietors of these places, and prove ‘drawing cards.’” The report’s derisory tone reflected the widespread sentiment that had grown among many members of the press, in addition to a large segment of Winnipeg’s population, that the city’s variety theatres were an offence to public decency.

Liquor sales accounted for most of the theatres’ revenues, and alcohol-fuelled rowdiness among the all-male spectators, in addition to the lewd nature of many of the acts, drew the scorn of reform organizations, including the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and Blue Ribbon Society, as well as several members of Winnipeg City Council.

Wrestling’s close association with the city’s generally disreputable variety theatre business certainly did not help its standing. Nevertheless, such entertainments had wide appeal among men that transcended class boundaries, and even well-to-do citizens often attended the shows, while other people of the same social station decried them.

About Manitoba 150 Excerpts

May 2020 marks Manitoba’s 150 anniversary as a province of Canada. The Manitoba Act was passed by the Parliament of Canada and received Royal Assent on May 12, 1870, creating the Province of Manitoba. To celebrate, throughout the year we will be posting excerpts from some of our titles that touch on Manitoba’s history, people, and cultures.

Posted by U of M Press

June 8, 2020

Categorized as Excerpt, MB 150

Tagged community, culture, history, manitoba, manitoba 150, masculinity, mb 150, men, prairie, sport, sport history, winnipeg, wrestling

Injichaag nominated for Indigenous Voices Award! Manitoba 150 Excerpt #3: Structures of Indifference