During the first half of the twentieth century, Winnipeg Beach proudly marketed itself as the Coney Island of the West.

Located just north of Manitoba’s bustling capital, it drew 40,000 visitors a day and served as an important intersection point between classes, ethnic communities, and perhaps most importantly, between genders.

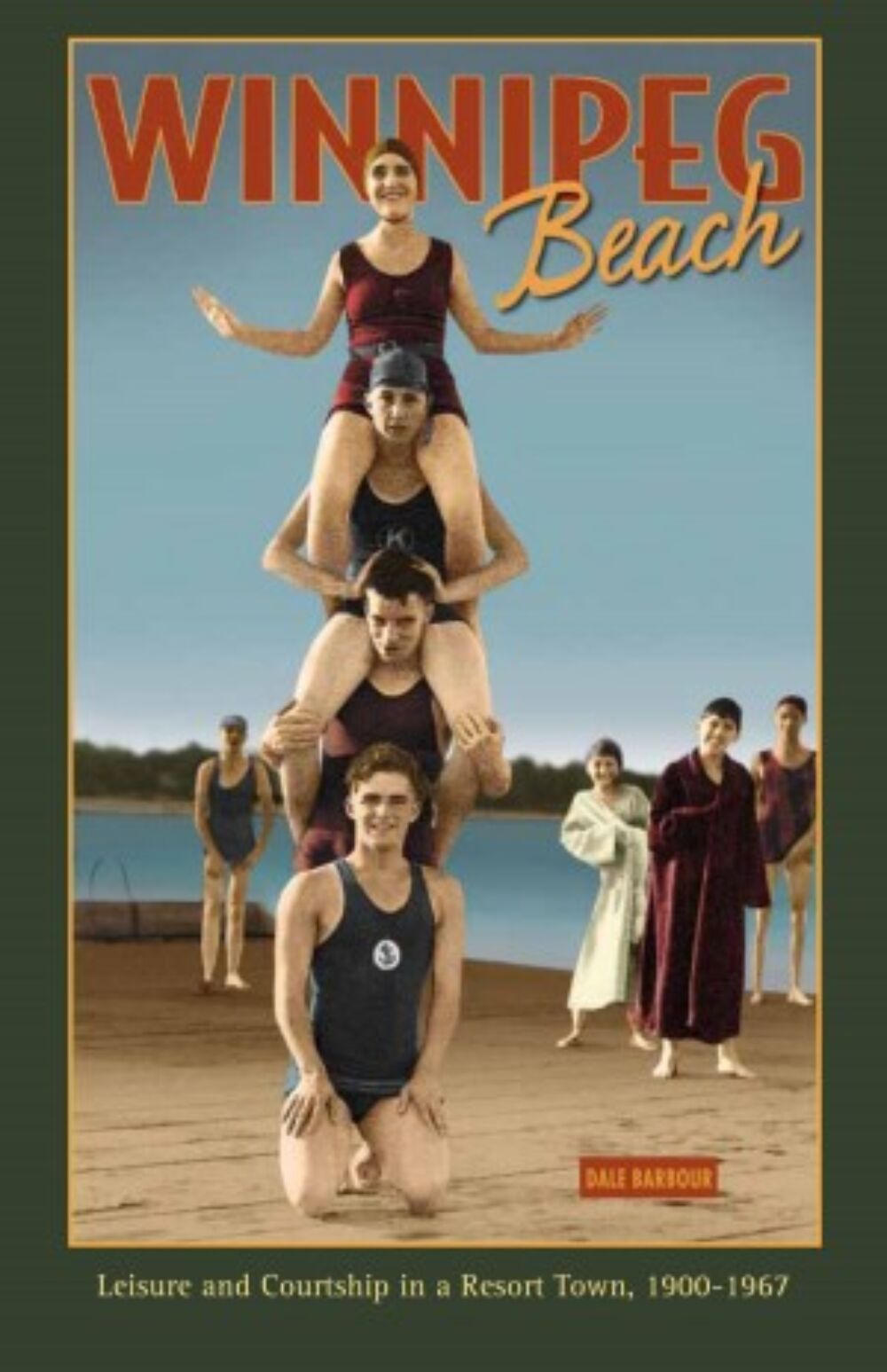

In Winnipeg Beach, Dale Barbour takes us into the heart of this turn of the century resort area and introduces us to some of the people who worked, played and lived in the resort. Through photographs, interviews, and newspaper clippings he presents a lively history of this resort area and its surprising role in the evolution of local courtship and dating practices, from the commoditization of the courting experience by the CP Railway through their “Moonlight Specials,” through the development of an elaborate amusement area that encouraged public dating, and to its eventual demise amid the moral panic over sexual behavior during the 1950s and ’60s.

This book is an important addition to our history list because it uses history as a lens through which to examine issues around leisure, courtship, and sexuality.

*

Excerpt from Chapter Three: Playing at the Beach

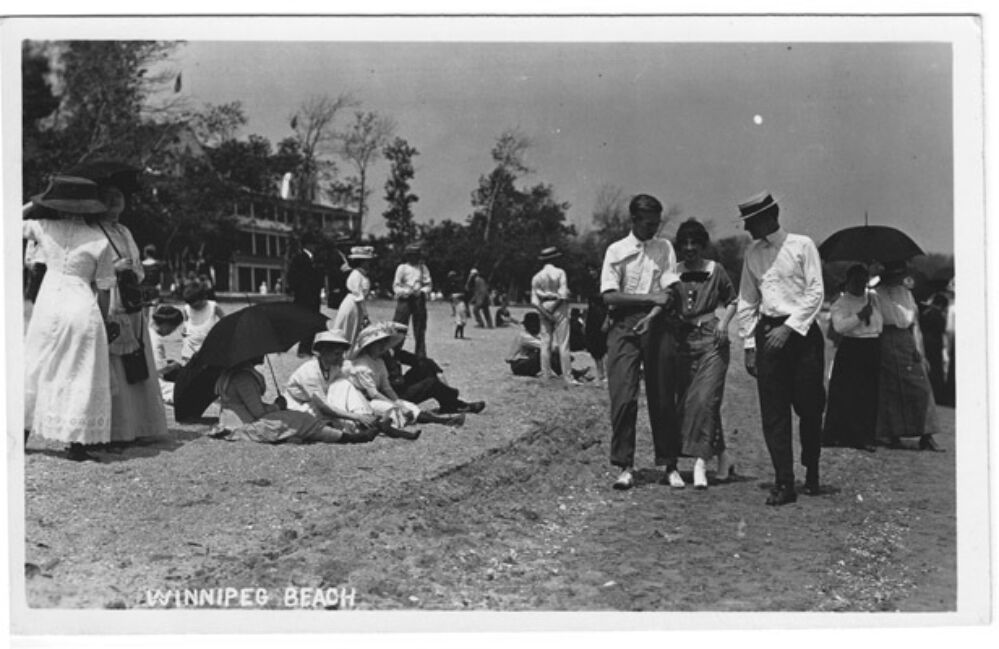

Once on the boardwalk, the individual people merged into a spectacle of people, noise, and excitement.

The differences that divided Winnipeg Beach’s diverse population did not disappear; friends clustered with friends, men and women promenaded in an effort to attract the opposite sex, and ethnic differences remained. And yet everyone was willing to join a collective experience.

The boardwalk depended on both the crowd and the commercial amusements to create the excitement. Winnipeg Beach’s boardwalk became a place for men and women to date and flirt and play because people brought that expectation into it.

Without the people and their urge to have a good time, Winnipeg Beach’s spectacular roller coaster was merely a piece of equipment. But with groups of people screaming as they careened around the corners and clutching each other closely it became something more.

Being part of the spectacle released people from the conventional behaviour and restraints of daily life, and, like the dance halls, such parks were places where young people could meet “without embarrassment within the sanctioned conventionality of the midway.”

The boardwalk linked the dance hall, beach, and rides and was fed directly by the train station. Dr. Paul Adams can remember meeting the trains at Winnipeg Beach in his youth and watching the people flow out of the train station. Many of them would head directly “on to the boardwalk either to spend money there, go on the amusements or to just watch. Because there was excitement there. There was activity.”

Lawrence Isfeld had similar recollections: “With all the rides going, it was busy, it was like the hype. You know the merry-go-round was going around, the bumping cars, the planes were going, and the roller coaster. Yeah, things were happening. It was, people wanted to be there, because there was action going on.”

The bumping cars and the roller coaster followed in a proud tradition of amusement park games whose goal, at least in part, was to allow men and women to be “bumped” together, challenging gender boundaries ever so slightly.

Looking back at the 1940s, Val Kinack could recall that “the attractions didn’t open until six o’clock, I think. We always knew they were open because there was a calliope that would be down there and it used to start playing and you could hear it all over the beach. So when we heard that we knew things were going. This is when we were younger and we’d high tail it down to the beach.”

Just as the train whistle would alert people to the arrival and departure of the train, the calliope, a mechanical steam organ, would tell them when the boardwalk had been switched on.

The calliope also came to symbolize the beach for Christopher Dafoe when he tried to trace the decline of Winnipeg Beach and argued that, as the area became more of a focal point for men trying to pick up women in the 1950s, “the merry-go-round music of the steam calliope became the slightly obscene wail of the saxophone.”

The boardwalk offered a little something for everyone; heading south from the dance hall, patrons could check out the movie theatre or head into the bowling alley, wander past the games of chance and maybe win some chocolate, and then move on to the rides such as the merry-go-round, dodgem cars, airplane ride, small Ferris wheel, or the beach’s signature roller coaster.

An interview subject who self-identified as a retired CNR worker could recall racing to the boardwalk with his friends on their bikes in the 1950s, and even fifty years later he could remember the distinctive feel of the roller coaster, which was built in 1919 but was still the main attraction in the 1950s when he was going:

“It was a wooden structure. It moved. You know when you were going around corners the whole structure moved,” he recalled.

There was an element of male and female interaction in all of this. Dr. Paul Adams could recall “the young sparks” fishing out change to take their girlfriends on a ride. But it also was simple escapism and performance.

Married at just sixteen, Susan travelled to Winnipeg Beach with her husband and a group of friends to take part in the rides and the dance hall. Some of her strongest memories are of being banged about in the bumper cars and of riding on the roller coaster twenty-three times in a row.

She was not alone. Victor Martin said he and his friends would start their evening on the boardwalk. The “big attraction for us was riding the roller coaster; you went around and didn’t hang on. As soon as you held on you were chicken. That was the biggest thing we got a kick out of,” Martin recalled.

“Rides were cheap, you just stayed on, I know one guy would go down and just about handcuff himself into [the roller coaster].”

Nestor Mudry, who travelled to Winnipeg Beach in the 1930s and 1940s, could remember the boardwalk being lit up and a corridor of lights running from the boardwalk to the train station, which was also lit up.

In this Winnipeg Beach reflected its larger cousins at Blackpool or Coney Island, where Luna Park’s “200,000 lights guaranteed decency even as they created feelings of freedom from constraint.”

Lights helped control the use of space, and at Winnipeg Beach lights equated to public zones such as the boardwalk and the walkway to the train station, while a lack of lights equated to the anomalous zones of darkness, such as the beach at night or the forest of trees that surrounded the dance hall and grew to the south of the roller coaster.

Once again, lights provided moral security: the skinnydipping and spooning that had happened during that summer evening in 1906 would never have occurred had the beach been lit up.

About Manitoba 150 Excerpts

May 2020 marks Manitoba’s 150 anniversary as a province of Canada. The Manitoba Act was passed by the Parliament of Canada and received Royal Assent on May 12, 1870, creating the Province of Manitoba. To celebrate, throughout the year we will be posting excerpts from some of our titles that touch on Manitoba’s history, people, and cultures.

Posted by U of M Press

August 6, 2020

Categorized as Excerpt, MB 150

Tagged community, courtship, culture, history, leisure, manitoba, manitoba 150, mb 150, men, photography, resort, tourism, train, winnipeg, winnipeg beach, women

Treasure hid in a field Isabelle St-Amand on Indigenous cinema and media