Gerald Friesen is one of Canada’s most respected historians. His book The Canadian Prairies, has been a best-selling history of the region since its publication in 1987. A long-time member of the University of Manitoba history department, Friesen was the founding general editor of UMP’s ground-breaking series Manitoba Studies in Native History (now known as Critical Studies in Native History). Under his leadership, this series published many ground-breaking books on Indigenous history.

Friesen’s collection of essays, River Road, was published by U of M Press in 1996. It represents his wide range of interests, from labour history to Indigenous history to the ways in which regions see themselves and their culture. This excerpt from the title essay looks at the fascinating story of River Road, the historic byway running along the Red River north of Winnipeg. It focuses on the prosperous and prominent Metis families who lived on River Road in the nineteenth century.

“River Road” was co-written with another distinguished Manitoba historian, Jean Friesen, who besides a career at the University of Manitoba made her mark in public life as a cabinet minister and deputy premier in the Gary Doer government.

*

There is a River Street in Prince Albert, a River Street in Moose Jaw, a Riverside Drive in Saskatoon, and many more thoroughfares of similar name throughout the Canadian prairies. The label is common be- cause the road beside the river was the path in the community when the Europeans—and their urge to label places—arrived. This is the story of the first River Road in prairie Canada, the main artery of St. Andrew’s Parish near Lower Fort Garry, Manitoba.

The Red River was once a highway and a treasure house of resources. Along its banks travellers camped, particularly near meeting places such as the Forks, where the Red and Assiniboine converge. Its waters teemed with fish. In spring and autumn, migrating ducks and geese filled the air above its course. Near the river grew groves of maple trees, the sap of which was a prized food item. At one favoured point, the maple grove near “the rapids” (where St. Andrew’s Church now stands), Aboriginal encampments would have been occupied every year for at least thirty centuries.

When Europeans and Canadians settled in this land in the early nineteenth century, they, too, travelled the river and harvested its riches. As their settlement became more densely populated, and particularly as traffic increased between the two posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), Lower Fort Garry and Upper Fort Garry, a straight highway was built some distance inland from the river, leaving the path along its west- ernbank as a parish road.

The modern evolution of River Road and of its more prominent accompaniment, the King’s Road, can be traced in the maps of the Red River Settlement and the province of Manitoba. The Inner Road, as the River Road was called, appears as early as 1836, and is unmistakable in 1858 and 1875 maps of the district. When the provincial road system developed in the 1870s and 1880s, the riverside trail seems to have been ignored. After the advent of the automobile and the modern highway in the first three decades of the twentieth century, when the King’s Road, by now a commercial route between Selkirk and Winnipeg, became a “first class trunk road,” the Inner Road did not appear on some highway maps and, on others, was a “third class local road [off our possible classes], well travelled.”

For a century and a half, River Road has served as the thoroughfare for an extended village, a kind of back street for a parish that had no proper main street because it possessed too little commerce to require anything so grand. It was a ten-kilometre trail that meandered from river lot to river lot with no larger purpose in view than to reach the next neighbour and, eventually, the church. It was the path along which neighbours strolled and gossiped, children played, and animals moved to work or to market It was always dusty in high summer, frozen and windswept in deep winter, and a muddy, impassable quagmire during the brief prairie spring.

The pace of River Road was once the pace of oxen and school children. News travelled along the road by word of mouth or, occasionally, by printed decree from the Council of Assiniboia. The passage of time was measured by the sun, the seasons, and the task at hand. The community that developed along this road between the 1830s and the 1880s is not immediately evident today, but its ambience can be discerned in the hedges of the old river lots, in the bluffs of trees and the circling pelicans and the slow movement of the river, in a marsh that has developed in a disused limestone quarry, and in the remaining buildings, Scott House, Kennedy House, Hay House, Twin Oaks, and Si Andrew’s Church and Rectory.

To recover the atmosphere of the nineteenth-century pathway, one must reconstruct one’s sense of land transport in an age before automobiles. Road traffic was notoriously difficult in North Atlantic countries until the Industrial Revolution. In England, for example, roads in 1760 were probably worse than they had been in Roman times. The King’s Highway, which had a special legal standing, merely offered a right of passage to the king and his subjects. It did not promise comfort or safety. When the road was blocked by mud or obstructions, its royal designation entitled travellers to break through fences and to detour through fields or the grounds of houses in their quest for a firm track. The maintenance of parish roads depended upon statute labour, a legal obligation imposed upon landholders that involved a certain amount of work, or its equivalent in tax payment, each year.

River Road belonged in the category of informal thoroughfare, and, despite a number of disputes between landholders over its precise path, it never attained legal standing in the years of the Red River Settlement. If it was maintained at all, the work was undertaken by those who lived along its length, often as a result of the urgings of the Council of Assiniboia. Each male householder was supposed to give three days’ labour or three shillings to mend roads, fill in washouts, and build wooden bridges.

In its early years, the road always took second place to the river. The Red River Settlement, like the pioneer communities in New France and along the Great Lakes, was based upon river lot (or lakefront) agriculture. The pattern of landholding was determined by the central role of water transport in these communities and by the importance of the river in winter, both as highway and as source of ice for food preservation. The river lot also provided equitable distribution of wood and hay resources, both of which were abundant in the river valleys and could be allocated easily by the creation of long narrow lots stretching back from the river itself. The path that inevitably developed on the bank might be used when ca- noe or sleigh were unavailable, or when floating ice made river travel dangerous, but it was an inferior alternative to the waterway.

The legal foundation of landholding in European terms was established when Lord Selkirk negotiated a treaty with Chief Peguis in 1817. This pact enabled Europeans to assume control of territory along the Red River to the distance at which daylight could be seen under a horse’s belly – about two miles, it was said. The arrangement was formalized, in European eyes, by a HBC survey. In St. Andrew’s Parish, the survey fixed the width of most river lots at three to six chains, the depth at two miles. On these lots, fur traders and their wives settled in the 1830s and 1840s to create the various parishes of the Red River Settlement.

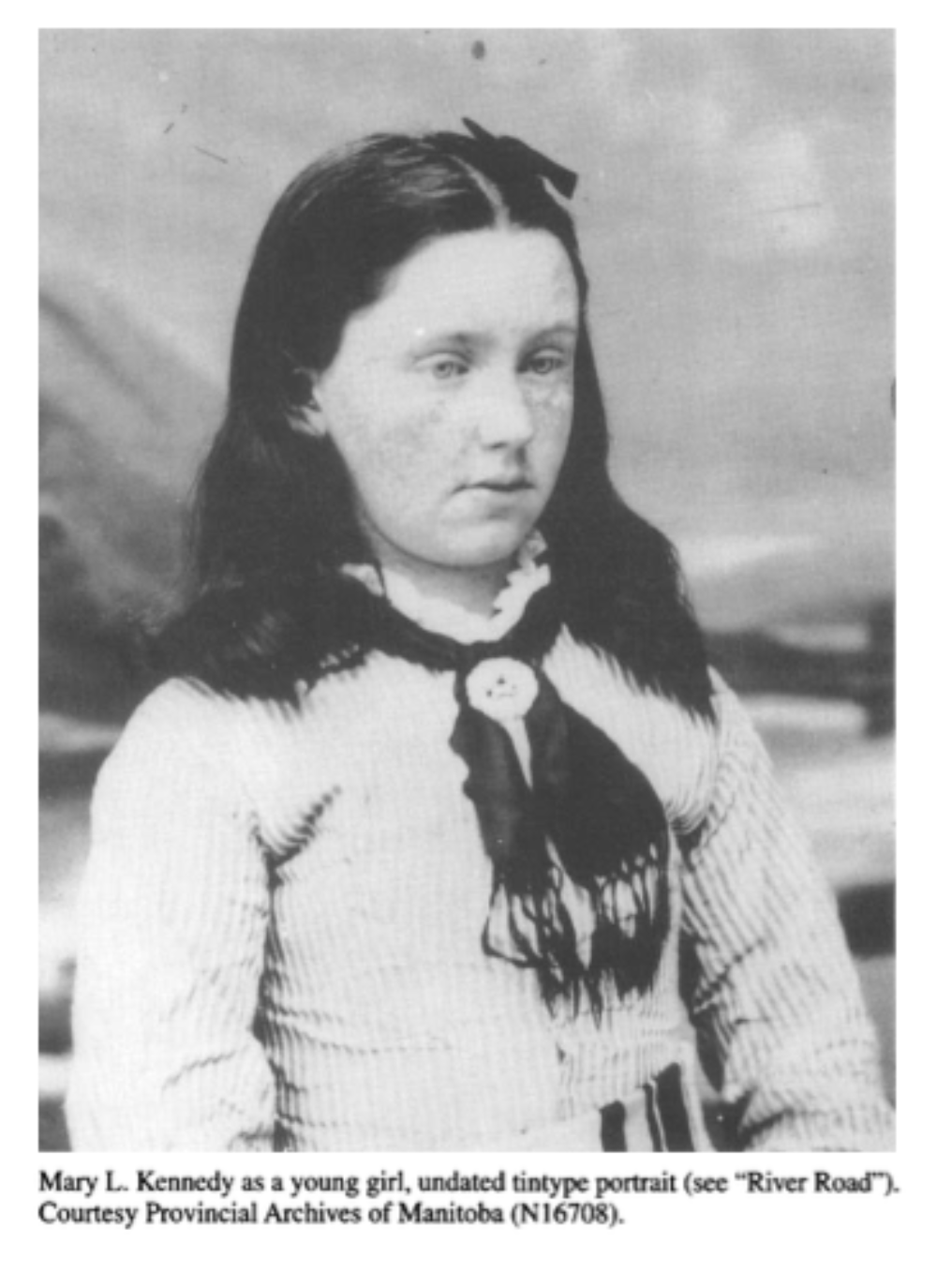

One of those families was founded by Alexander Kennedy and Aggathas Bear. Alexander left his native Orkney Islands at the age of seventeen to become a clerk in the HBC. He married Aggathas in 1804, when he was living near The Pas on the Saskatchewan River. They had nine children. Around 1831, Alexander arranged to buy a lot in St. Andrew’s Parish, at a prime site near the rapids and the Anglican mission, and then returned on a furlough to Scotland. He wrote Aggathas: “I intend to take Roderick and Alexander home [to Orkney] with myself and if I am alive, please God, I shall see you again next summer. In the meantime do not want for anything that I can afford to supply you with either for yourself, your mother, or the little ones, and be assured that as long as I live I shall never forsake you nor forget you, and if I die I shall not forget you.”

Alexander did die during this furlough, in England in 1832, but Aggathas took up the land in St. Andrew’s Parish with the three children still at home. The census reported that the “widow Kennedy” presided over a house, a stable, a barn, and seven cultivated acres. She possessed a horse, oxen, cows, calves, and pigs; in the yard lay harrows, plough, cart, and two canoes. And her children? A doctor, a schoolteacher, two wives of distinguished fur traders, a storekeeper, a farmer, and one, William, who returned to the parish lot in St. Andrew’s to build a fine stone residence for his English wife and to lead the life of a gentleman. Until her death, Aggathas resided in the original log dwelling situated a few steps from the imposing new home of her son.

About Manitoba 150 Excerpts

May 2020 marks Manitoba’s 150 anniversary as a province of Canada. The Manitoba Act was passed by the Parliament of Canada and received Royal Assent on May 12, 1870, creating the Province of Manitoba. To celebrate, throughout the year we will be posting excerpts from some of our titles that touch on Manitoba’s history, people, and cultures.

Posted by U of M Press

May 19, 2020

Categorized as Excerpt, MB 150

Tagged community, history, indigenous, manitoba, manitoba 150, mb 150, metis, prairie, red river

A Diminished Roar nominated for Manitoba Day Award! Injichaag nominated for Indigenous Voices Award!