University of Manitoba Press is a member of the Association of University Presses, which this year will celebrate University Press Week from November 12-17. This year’s theme is #TurnItUP, which emphasizes the critical role of university presses in providing a voice for authors, ideas, and communities beyond the scope of mainstream publishing.

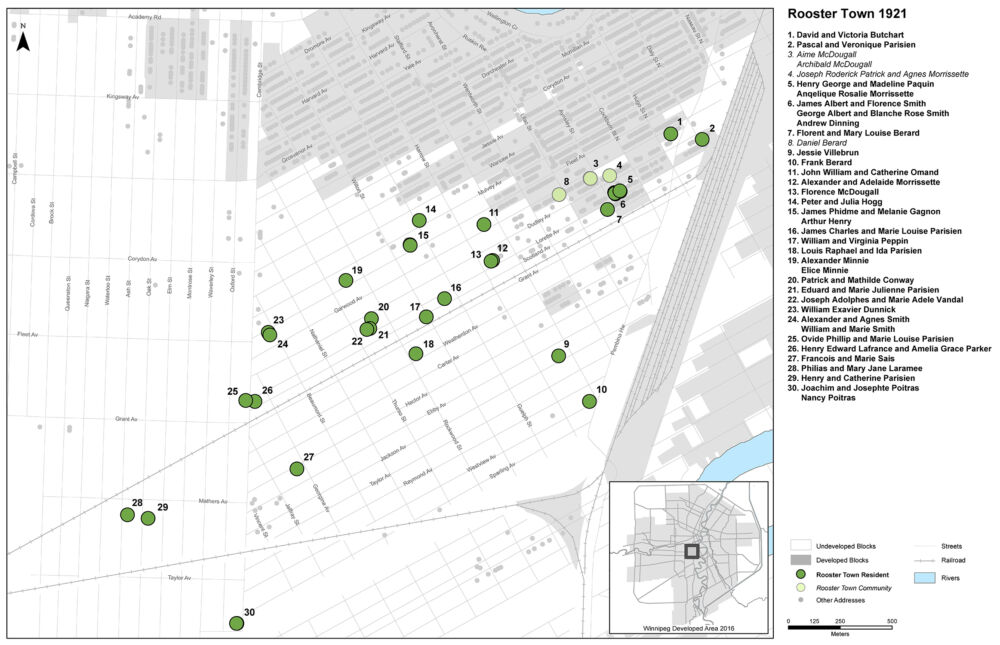

We’re participating in this year’s blog tour. Today, blog posts from university presses across the continent will focus on “The Neighbourhood” and we couldn’t think of anything better than GIS specialist and Rooster Town co-author Adrian Werner talking about how he used mapping to make Rooster Town, a Metis community that persisted on the southwest edge of Winnipeg for six decades, visible. Enoy!

*

In 1911 when Ida Parisian was about 12 years old, her parents moved from St.Norbert to Rooster Town. Growing up she lived within one block of ten other Métis families. She would marry Louis Raphael Parisian, raise a family, and live in Rooster Town until the lot they lived on was sold to Grant Park Plaza in 1956.

Her family’s story is one of the many histories told in Rooster Town: The History of an Urban Métis Community, 1901-1961.

By talking about this community’s diversity, resilience, and adaptation we challenge a process that settler cities used to dispossess indigenous people: containment, expulsion, and erasure. Maps play a critical part in all three processes but were particularly useful for erasure. They present land as empty, renaming the places and neglecting to tell the histories of past ownership, use, and value. The result is that indigenous places have been “mapped out” of prairie urban history. As we continue the journey toward reconciliation we must re-map. For Rooster Town, we found that placing the community in space was critical. It helped us construct many of our community profiles, identify which community members we were missing, and understand the underlying processes of dispossession, erasure, and misrepresentation.

There are challenges when we try to reconstruct the record of a community that has been erased. During the mapping process we hope that we can also begin to stitch Rooster Town’s history back together through administrative data, maps, and other records. Doing this requires caution so we fact-checked our maps against multiple sources so we could locate people with a higher level of confidence. This technique can be used by anyone who is willing to take the time to collect the records. Most of this information is free online, although some records require visits to archives or subscriptions to services. We will use the example of Louis and Ida Parisian to demonstrate our mapping process using the 1921 Canadian Census and several other supporting sources.

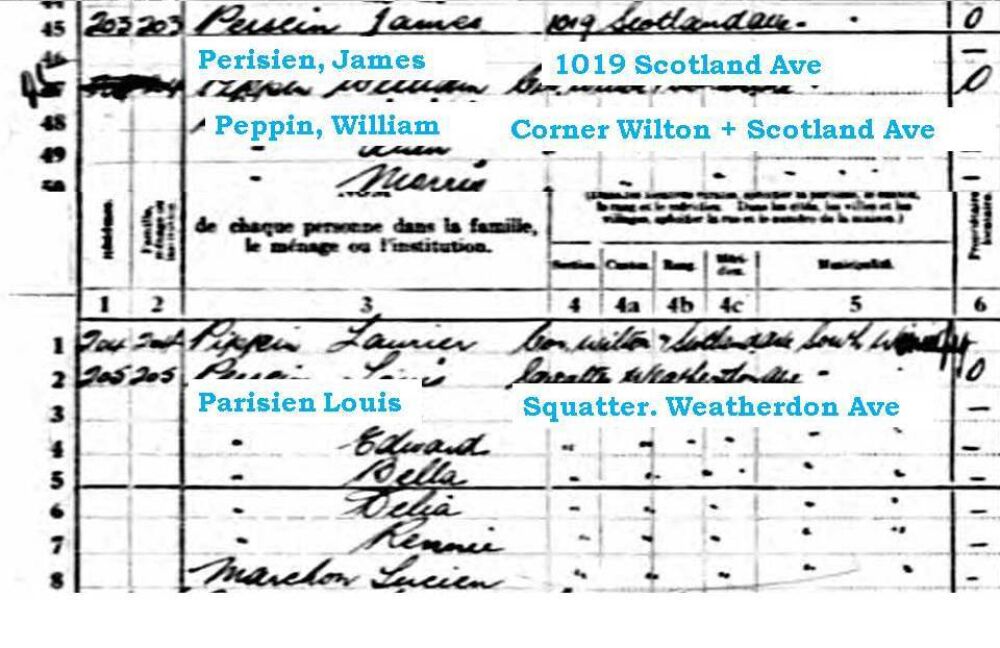

Addresses generally come in four formats in historical records: 1) mappable property descriptions such as Est 25/7 Pl 1606 Bk 41, Lt 17/18 which reference which river lot, plan number, and block a property belongs to, which are very accurate but not always easy to map; 2) street address, like 1019 Scotland Ave, which are usually accurate and mappable; 3) intersections such as the “Corner of Wilton and Scotland”, which are easy to map but are less accurate; and 4) descriptive addresses like “Louis Parisien. Squatter. Weatherdon Ave”, which are very challenging to map and hard to find.

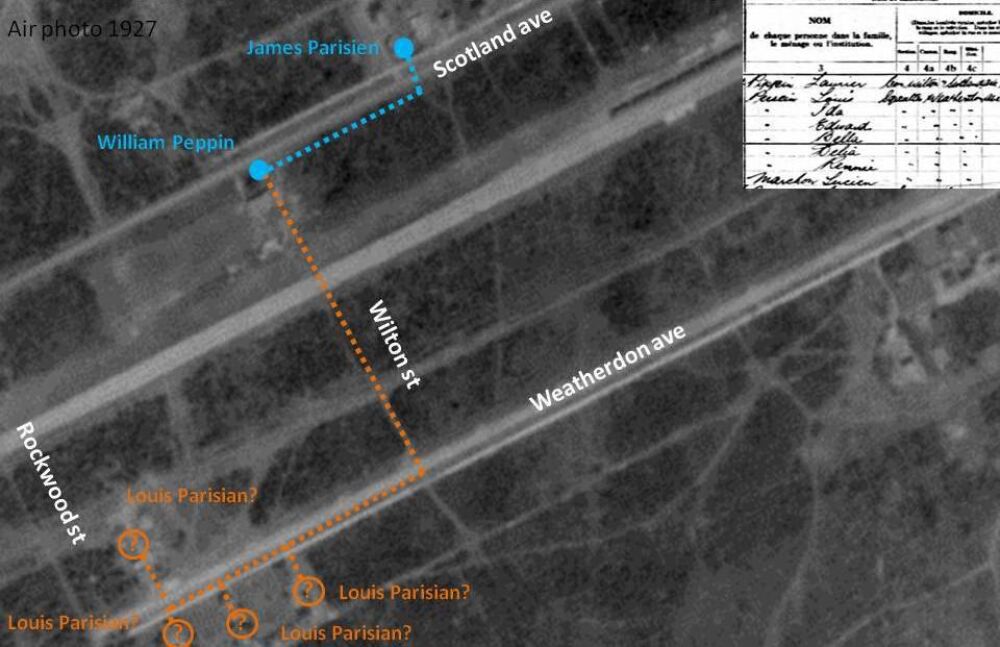

To figure out where descriptive addresses like Louis and Ida Parisien’s were located we start by looking for sources like air photos or old maps that give us an idea of how the place may have appeared when the census was taken. In this case we were fortunate to have air photos from 1927 and 1929.

By combining an air photo and the order that people were interviewed for the census we can determine the probable direction that the census taker was walking. We know the census taker visited 1019 Scotland right before interviewing William Peppin’s family at the corner of Wilton and Scotland because no one is recorded between those households. From there they walked to Weatherdon, and the shortest route available would have been to take Wilton. From this we know that Louis and Ida Parisien’s house was either the first one to the left of Wilton on Weatherdon, or the first to the right, but we need an additional source to determine which it is.

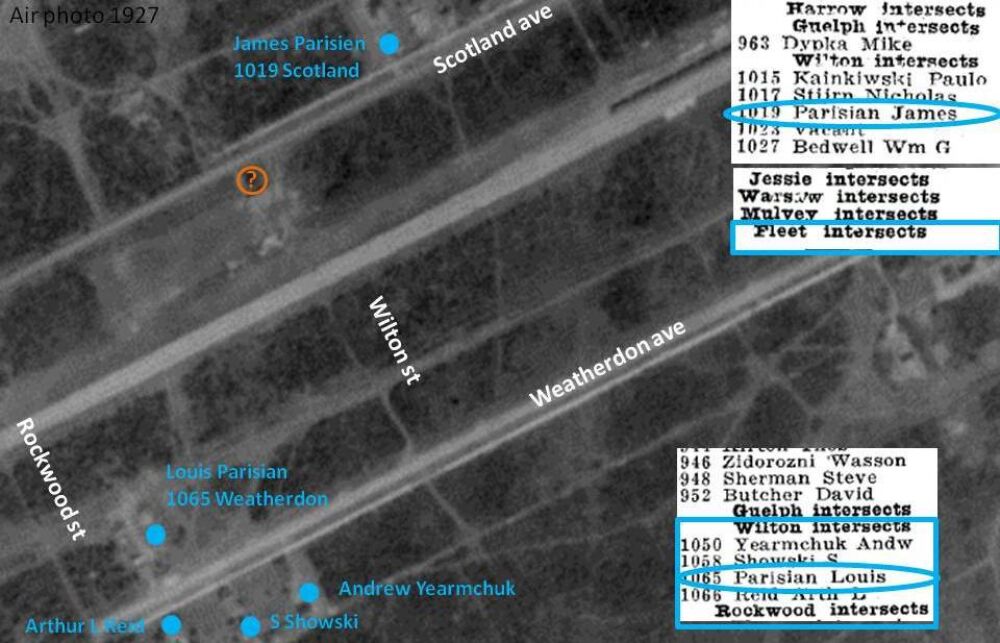

The next source to check for an address is the Henderson’s Directories. They are updated yearly starting in 1878 but it often misses people. Louis Parisien is listed as living at 1065 Weatherdon in 1932, 11 years after the census recorded him living in that area. This is useful, but a third source helps confirm the address.

In the case of Louis and Ida Parisien we are extremely fortunate to have a building permit from June 15th 1920 for a 2 storey 12×18’ house, and that it is on Weatherdon between Wilton and Rockwood, Est 25/7 Pl 1606 Bk 41, Lt 17/18. This additional record places them beyond a doubt at 1065 Weatherdon by 1921.

Despite the challenges of mapping this community we found that situating the community in space was critical to our research. Remapping became the framework from which we could find people, identify trends, and mark changes. By placing Métis communities like this one on the map, we can start to tell the history of urban indigenous communities and the colonial institutions that created and destroyed them.

Bibliography:

- Brealey, Ken G. “Mapping Them ‘Out’: Euro-Canadian Cartography and the Appropriation of the Nuxalk and Ts’ilhqot’ in First Nations’ Territories, 1793-1916.” The Canadian Geographer 39, no.2 (1995):140-56.

- Canada. Dominion Bureau of Statistics. Census of Canada, 1921. Ottawa: King’s Printer. http://www.bac-lac.ca/eng/census/1921/Pages/introduction.aspx

- Canada. Natural Resources Canada. Aerial Photograph of part of Winnipeg. Photo A1221_009. Ottawa: National Air Photo Library, 15 July 1929

- Henderson Directories. Henderson’s Winnipeg Directory, 1932. Winnipeg: Henderson Directories. http://peel.library.ualberta.ca/bibliography/921.4.13.html

Posted by Adrian Werner

November 14, 2018

Categorized as Author Posts

Tagged books, census, community, gis, henderson's directory, history, indigenous, manitoba, map, mapping, metis, prairie, research, rooster town, winnipeg

Structures of Indifference at McMaster Igloolik Island, a Mythical Place