It can be difficult to stand apart in a city known for its iconoclasts, artists and outsiders, but photographer and filmmaker John Paskievich has been doing just that with grace and good humour for over forty years now in Winnipeg.

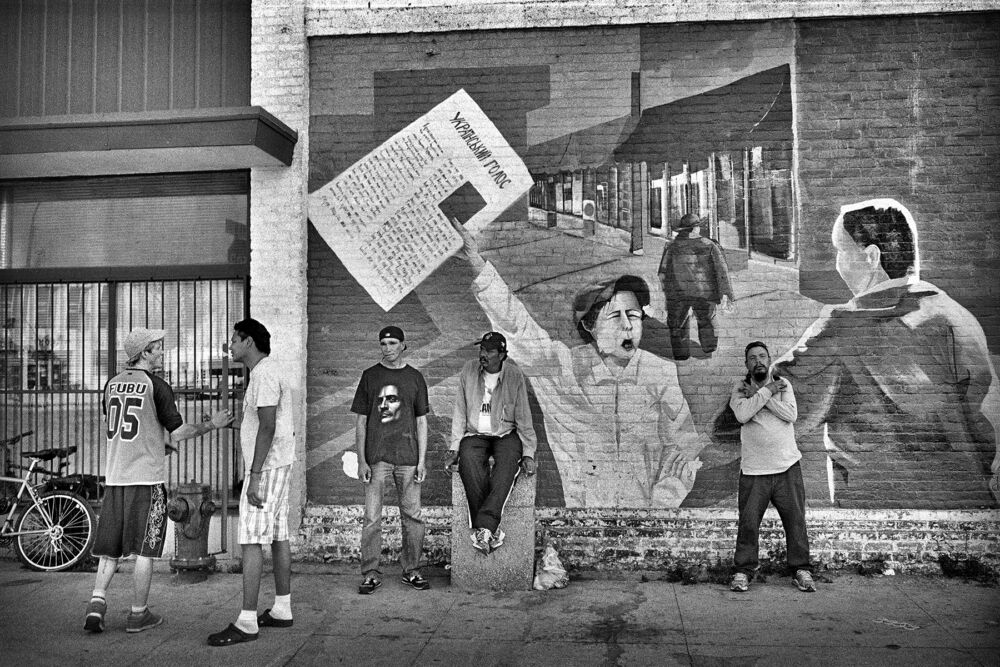

A humble start in photographing the people and places he knew from growing up in the North End has become an invaluable and unique archive of a neighbourhood that’s storied but often misunderstood.

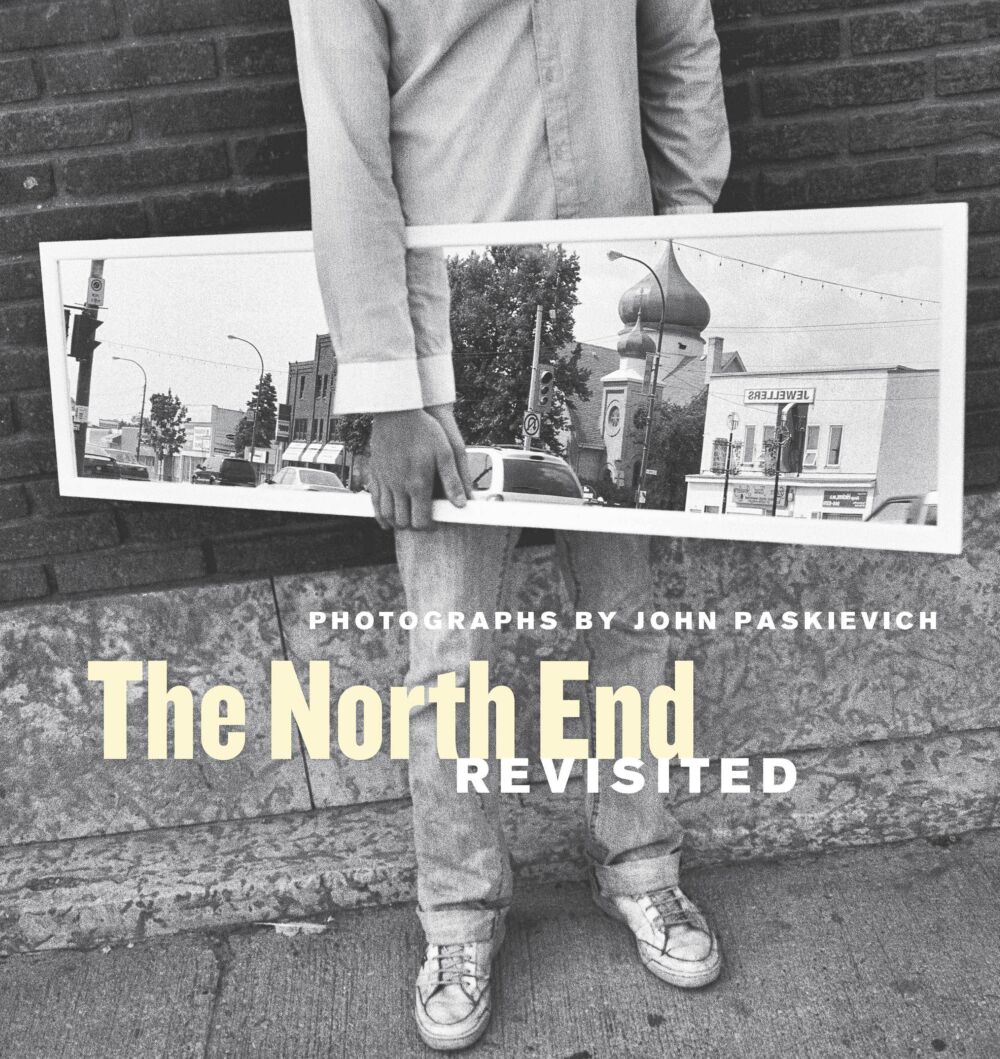

Now, after four decades photographing the North End, Paskievich is helping the University of Manitoba Press mark five decades in publishing with an update to his 2007 photo book The North End titled, appropriately, The North End Revisited. It contains 80 previously-unpublished photographs, both recent and of an older vintage, along with essays and an interview with the artist.

John Paskievich sat down with Winnipeg photographer Colin Corneau recently for a talk on photography, shoes and being an outsider.

Colin Corneau: So, I’ll just jump into it with my first question: What kind of shoes do you have? And the reason that I ask that is that one of the best pieces of advice I got about street photography was “Wear good shoes.”

John Paskievich: That’s right! That’s very excellent advice. I like K-Swiss sneakers. I’m wearing a pair of K-Swiss sneakers right now. I find that they’re the most comfortable shoes that I’ve ever worn.

CC: Any endorsement deals coming?

JP: Not that I know of! But I’d be happy to get one.

CC: We hear the term bandied around a lot: street photography—is that a legitimate term for you? How do you think about that term? How do you classify what you do?

JP: I guess it’s as good as any. Street photography happens in the street; it also happens in the back alleys, happens on peoples’ porches, on the sidewalks…I like to think of it more as “urban”, urban photography, whatever catches my eye in an urban setting. I also take a lot of pictures of buildings; it’s not the best way to take pictures of buildings with a 35mm camera. I take a lot of pictures of buildings but I don’t print them…

CC: Why is that?

JP: I don’t think they’re that strong, but they interest me. They’re not that strong because buildings require a larger negative to look at the detail, but I’ve got a 35mm camera so I take the pictures of the houses—some little houses nestled in there where the garbage cans are almost as big as the house, that kind of stuff.

CC: So why are such pictures important? I do them a lot and I know you’ve had forty-plus years of taking them; why are these pictures important, of public spaces, of people living their life? Why do they matter?

JP: Well, they might not matter now, to the viewer. They matter to the viewer now who likes photography, because a photograph is a photograph. It’s like a painting: if you like it, you like it. There’s a saying that after 20 years, every photograph is a good photograph, either as historical record or as more than historic record it provides not just history but the ambience of the time, what people wear. It’s a time capsule; it’s magic. And not only for the historical record but it brings out the emotions of people who might not have been at that time, but perhaps their grandparents were there at the time and they have a relationship with their grandparents, so: “This is how my grandparents lived.”

CC: Do you subscribe to that theory? Do you really believe that photographs change and become something different over time, and somehow matter more?

JP: Yeah, I do. I do. But anything, over time, has a different value than right now. A 2015 Chevy Equinox has a certain value, but in 30 years that Equinox will have a different value. You can put the value how? Monetary value, nostalgic value, or aesthetic value. Time has a way of surprising you.

CC: So you mention people in the North End being distinct; is it conscious that in your films and your photos you always seem to be drawn to people just a little bit outside, which is interesting because I think that’s how photographers are; they’re just a little bit outside.

JP: Yeah, I’ve noticed about photographers, that they’re much more observant of the passing show. Every once in a while you come across people who are really emotionally invested in social issues, like Eugene Smith; he was very much into photography as a tool to show humanity but also to better humanity.

CC: Do you consider yourself a bit of an outsider in a way?

JP: Oh yeah, on all kinds of levels, but I don’t think of it as an outsider. I just like people who don’t buy into the usual so-called “received wisdom”.

CC: You’ve certainly encountered a lot of these people over the years, and a lot of different kinds of outsiders and a lot of people with different purposes to their lives. What have you learned from these photographs you’ve been taking in the North End from wandering around. Is there something you learned about people that you didn’t know before, or maybe just reinforced what you already thought?

JP: All things pass, all of peoples’ pretensions and hopes and dreams and chicaneries, and there are a lot of people with less education that have so much more interesting things to say and experience in their life than university profs or whatever. Humans are amazing.

CC: I guess that’s why Shakespeare is still relevant 500 years later—people don’t really change all that much.

JP: No. And certainly the -ologies, political ideologies try to change human psychology and it always fails, all this kind of social engineering. Not that you shouldn’t help people when they’re in need of help; absolutely, you have to.

CC: On that note, can such pictures—still pictures of the kind you’ve taken in the North End—do the same thing as a moving picture or film documentary, both of which you’ve done? You’ve already shown that those things can intermingle, in films like Ted Barlyuk’s Grocery where you mix together documentary and sound and turn it into a movie and blur a lot of those lines between still photos and moving pictures. Do you think that a still picture on its own can do the same thing as a moving picture can?

JP: A moving picture has more propaganda or teaching value because you can add a soundtrack to a movie and you can say: “That is a rich man,” or “That is a poor man.” But a picture, you look at it, and the guy looks poor but he could be very well rich. Ed Ackerman [the subject of Paskievich’s 2013 film Special Ed] is not a poor guy. He was raised in the Gates, and he’ll tell you himself that he isn’t poor. So some poor guy who likes to have a nice wardrobe, nice appearance, might look like he’s a well-off guy.

CC: So do pictures tell the truth, or not?

JP: No. Sometimes, but mostly not. It’s just a tiny little fraction of a second.

CC: I think it was Ansel Adams who said that there are two people in every picture: there’s the person being pictured and the person taking the picture, that they put a lot of themselves into it. Do you subscribe to that?

JP: Absolutely. The question is: “Why are you drawn to this subject, and why is the other person not drawn to this subject?”

CC: So why are you drawn to the North End?

JP: I feel that that’s been imprinted on me, those kinds of situations. I grew up in the North End, when I was a kid. I grew up in kind of not a continuous, secure, steady life. I was born in a displaced persons camp after the war, and then we lived in the downtown of Montreal where all the immigrants were, and then we moved to Winnipeg and I lived in Point Douglas. And when I went to school I just gravitated to those areas; I feel comfortable there.

CC: For what you enjoy shooting, what different quality would colour film or colour pictures bring to an image?

JP: I’m not sure. There’s a lot of good colour work; I’m not sure what it would bring except more colour. There was a prejudice actually; I don’t do colour but there was a prejudice, back when everybody was shooting black and white, that colour was not what “real” artists do in photography, that’s what National Geographic does. But some of those guys in National Geographic, man are they good. They are so good and they’re shooting in colour, so I never bought into that notion.

CC: Are black and white pictures viewed differently now than they would have been in the 70s or 80s? Is it almost a novelty now?

**JP:* It’s almost a novelty, it’s almost like lithography or etchings or something. *

CC: Are there any new projects in the works? Are you looking at any new projects, films, photographs or exhibits?

JP: Films; I’m busy with films now. I’m doing a sponsored film on the coming of age of the Ukrainian Canadians in the Second World War. So I’m working with that, using all archival material. And I just finished a little experimental film with Neil McInnes. And I’ve got a few other things. But in photography: I was up in the Arctic in the 80s, about six or seven times, and I took a lot of pictures and I’m going to see if I can compile them in a book, so I’m involved with that as well.

CC: Speaking of the future, do you plan to continue photographing the North End?

JP: Yeah, when I feel like it, or if there’s something interesting happening there— interesting-bad or interesting-good. I’ll go out there; I’ve just been out there when “that young guy on Main Street who was hit and run”:http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/fatal-crash-cop-winnipeg-1.4348975—the cop hit him—so I went over there to see what was happening. I took some pictures there.

CC: Let me know if you need any company, I’d be happy to go. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

JP: If you want to bring your camera, I’m going to be doing a presentation at Meet Me at the Bell Tower on November 10th at 6 o’clock on Selkirk and Powers. It’s a very interesting thing; they’ve been meeting there for six years, every Friday at six o’clock and it’s young people and it’s all in an effort to encourage young people to do good things and to stop the violence in the North End. So there’s a bell tower there where people gather and talk and then they ring the bell and go across the street into the Indigenous Family Centre, and that’s where I’m going to do my presentation. It’s important to know that’s going on there, because there are some people in the North End who are really great.

CC: John, thank you very much.

JP: I thank you Colin; it’s a pleasure talking about photography.

Colin Corneau is a Winnipeg freelance photographer. He spent 25 years as a daily newspaper photographer and has a particular interest in street and film-based photography. He can be found at www.colincorneau.com or on Instagram at @colincorneau.

John Paskievich was born in Austria of Ukrainian parents and immigrated to Canada as a young child. He graduated from the University of Winnipeg and studied photography and film at Ryerson University. His photographs have been widely exhibited and published in various periodicals and in several books, including A Voiceless Song: Photographs of the Slavic Lands, introduced by Josef Skvorecky, and A Place Not Our Own. His documentary films have garnered critical praise and won numerous awards. Paskievich lives in Winnipeg.

Posted by U of M Press

November 7, 2017

Categorized as Author Posts

Tagged art, black and white, books, film, history, north end, photography, pioneer, portraits, publishing, street photography, urban, winnipeg

Propaganda and Persuasion goes underground at the Diefenbunker! Sarah Carter receives The Governor General’s History Award for Scholarly Research!