On September 8th 2015, the world lost a truly remarkable literary voice.

We lost an uncompromising intellectual visionary, a fount of linguistic, historical, and cultural knowledge, and a tireless advocate of Indigenous rights. Yet, the gifts with which Basil Johnston was so bountifully equipped continue to resonate, as they will for generations, through the words that he has left us and through his influence on those writers, Indigenous and otherwise, who have had the good fortune to come after him.

Johnston published sixteen books—novels, short story collections, children’s books, cultural treatises, memoirs—some in English, some in Anishinaabemowin, some bilingual. He produced language resources, teaching guides, thesauruses, and dictionaries. He wrote scores of newspaper articles and critical pieces. And he left indelible memories among those of us who had the privilege of hearing him speak and share his stories.

*

I really didn’t know Johnston all that well. I probably only spoke with him twenty-five times. But I can genuinely say that he changed my life. Twice.

The first time occurred when I was a twenty year-old literature student at a small Ontario university and, despite having taken courses in Canadian, American, Postcolonial, and Activist literatures, I hadn’t once encountered a literary text by an Indigenous author in any of my classes. This was back in the early 90s.

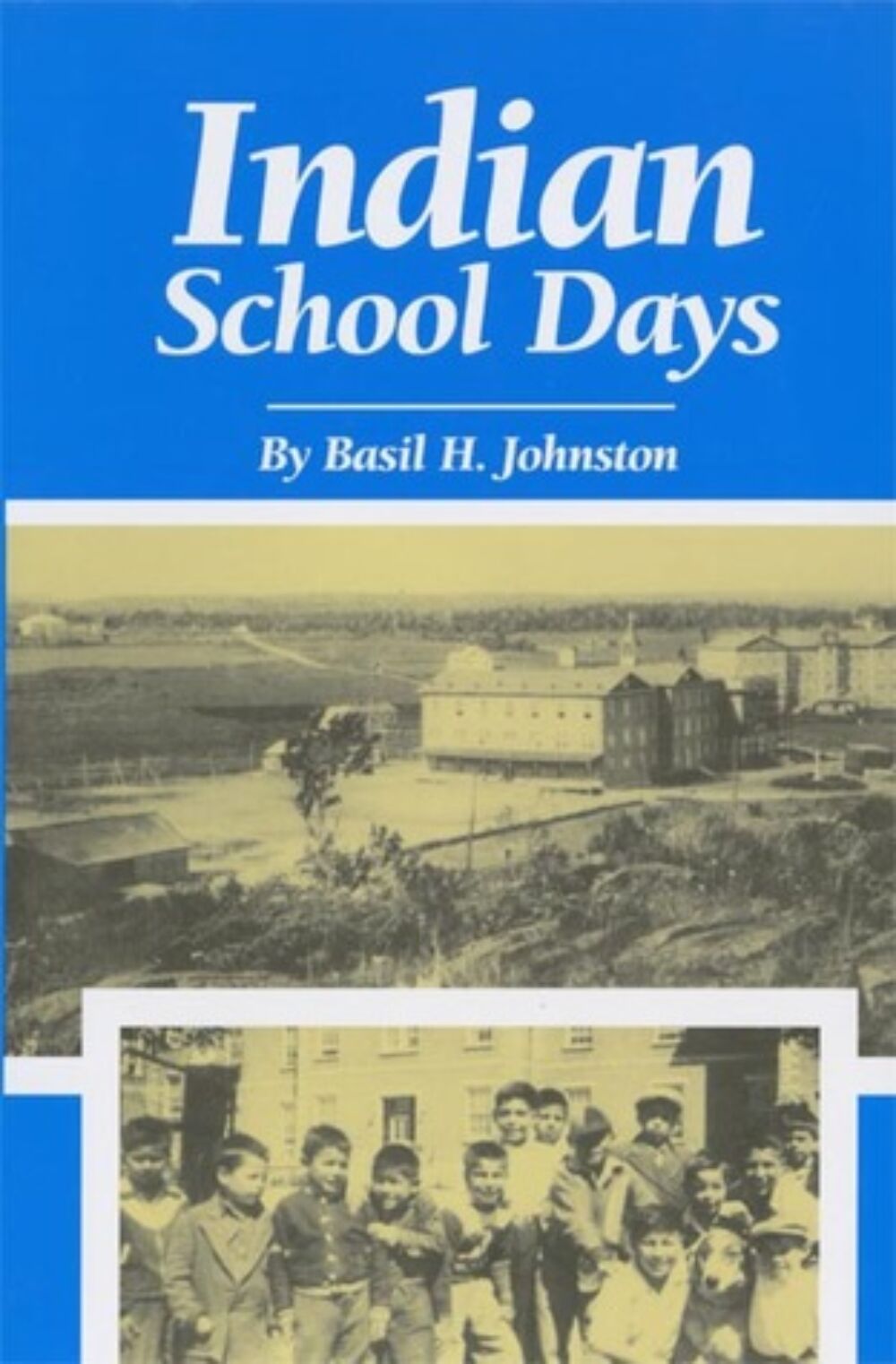

While doing some research for a history course, I happened upon Johnston’s residential school memoir Indian School Days, and I was shaken to my core—shaken by all that I, as a white settler Canadian, hadn’t known about my country’s history, and shaken as well by the courage, strength, and humour of the young Anishinaabe boys Johnston honoured in that book with the delicate precision of his words.

Indian School Days awoke in me a fire of passion and confusion and regret and wonder. It made me recognize that when woven together with vision and compassion, language has the power to fundamentally shift a reader’s understanding of her or his place in the world. And it made me respect more fully the integrity of culture and identity—both of which can endure, as Indian School Days shows us, even under the most oppressive conditions. After that I began to read as much Indigenous literature as I could find—first Johnston’s other books and then whatever I could get my hands on. When I decided a few years later to pursue graduate studies, I knew I needed to work on this body of literature. Inspired by Indian School Days, I ended up writing a dissertation on survival narratives by authors who had been through the residential school system—people like Johnston, Tomson Highway, Rita Joe, Anthony Apakark Thrasher, and Robert Arthur Alexie.Which brings me to the second life-changing moment.

When I had finished that project and was looking to get it published, a dear friend, the Anishinaabe poet, editor, and publisher Kateri Akiwenzie-Damm, offered to put me in contact with Johnston as they are both of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation. With her help, I sent him a copy of my manuscript with the faint hope that he might like it enough to write a small blurb of endorsement—you know, one of those “This book isn’t half bad, perhaps you should buy it and read it” statements that adorn back covers. Whether or not he agreed with any of my analysis, I hoped that he would recognize in the manuscript my profound admiration for his words and for those of the other survivors.

I remember vividly the day we had scheduled to discuss the manuscript over the phone. I was in my office in Calgary all dry-throated and nervous, walking back and forth to the hallway water fountain because I couldn’t sit still, waiting what seemed like an eternity for the time I was to call Johnston’s home at Cape Croker.

Johnston answered the phone and almost immediately he said, “Alright, I’ll do it. I’ll write the foreword to your book.” I was floored! I hadn’t imagined for an instant that he would dedicate such effort to my little academic project, never mind allow his illustrious name to be attached to it in such a significant way.

In the ensuing hour or so that we spoke, he explained why he was driven to again inject his voice into the discourse on the residential school legacy and to elaborate on what he had written decades before in Indian School Days. His words during our conversation were powerful and harrowing, yet touched by his characteristic humour and compassion. He spoke of experiences at residential school that he’d never before aired publicly, of the struggles within his community to pursue justice in the wake of this history, and of the loving relationships that sustained him throughout his life. All of these features are retained in the “Foreword” to Magic Weapons, which he so generously crafted with heartfelt, courageous, and uncompromising words. Nearly ten years later, that “Foreword” remains the single most important piece of writing with which I’ve been associated.

*

A short time later when I had the honour of interviewing him publicly at the Gladstone Hotel in Toronto, Johnston lamented “the loss of the sense of duty” in society. “The whole emphasis is on rights,” he said. “‘My rights are being violated.’ ‘My rights are being infringed upon.’ There’s not a word about duties. To the Anishinaabe, a right is debnimzewin. But each right is also a duty. And we’ve forgotten to teach those… So we have to go back to some of these values: responsibility, duty, right.”

I recall tears and laughter on that original telephone call I had with Johnston (from me anyways), and a sense of being called to responsibility—that he was offering me something valuable and by doing so was illuminating my ongoing duty to nurture the values expressed in that book. Looking back on that time, it strikes me that he was both giving me a gift and helping me to understand that truly honouring a gift involves tending to its endurance. This involves commitment—responsibility.

In Ojibway Heritage, Johnston talks about how individuality and self-growth are fostered in Anishinaabe culture as youth are “encouraged to draw their own inferences from the stories” and Elders make no attempt “to impose upon them views.” Much of the teaching I’ve received from Johnston over the years has followed this model. Whether in his books, his oral stories, or our conversations, he has left me charged with the task of unpacking the relevance of his lessons to my own experiences, according to my own gifts and predispositions. And I am forever grateful for every one of those teachings. Although as any who’ve met him will know Johnston had a commanding presence, he marshalled a subtlety that few possess.

With Indian School Days, Johnston unknowingly spurred me toward what would become my career, a career I feel endlessly blessed to pursue. With the “Foreword” to Magic Weapons, he offered me the interwoven gifts of credibility and responsibility. I am humbled by these gifts and the generosity of the man who gave them.

I’m also thankful that there is so much more I can yet learn from him. His published works yield fresh insights with each subsequent reading and I’m anxious to revisit them. (And, to be honest, he was so prolific that there are a few of his books that I’ve yet to read for the first time). Also, McMaster University in Hamilton houses the Basil Johnston Archives—five metres of shelving that holds a treasure trove of documents from throughout Johnston’s life. I look forward to spending days there enriching my understandings of this wise, brave, and uncommonly kind man.

In The Manitous, Basil writes about how “Nana’b’oozoo …. had done what everyone is supposed to do, to quest for that tiny knot of soil, the gift of talent, and to make from it one’s being and world.” Chii Miigwetch, Basil, for questing so unyieldingly for those talents in yourself and for sharing them with a world made more beautiful by your voice.

Sam McKegney

Kingston, Ontario

In the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe Peoples

September 18th, 2015

Posted by Sam McKegney

September 28, 2015

Categorized as In the News, Author Posts

Tagged anishinaabe, anishinaabeg, art, author, books, community, culture, elders, historian, history, identity, indigenous, launch, literature, media, memorial, ojibwa, ontario, scholar

Interrogating the Institutions and Ways of Being that Have Shaped our Present World The Idea of a Human Rights Museum as a Workshop!