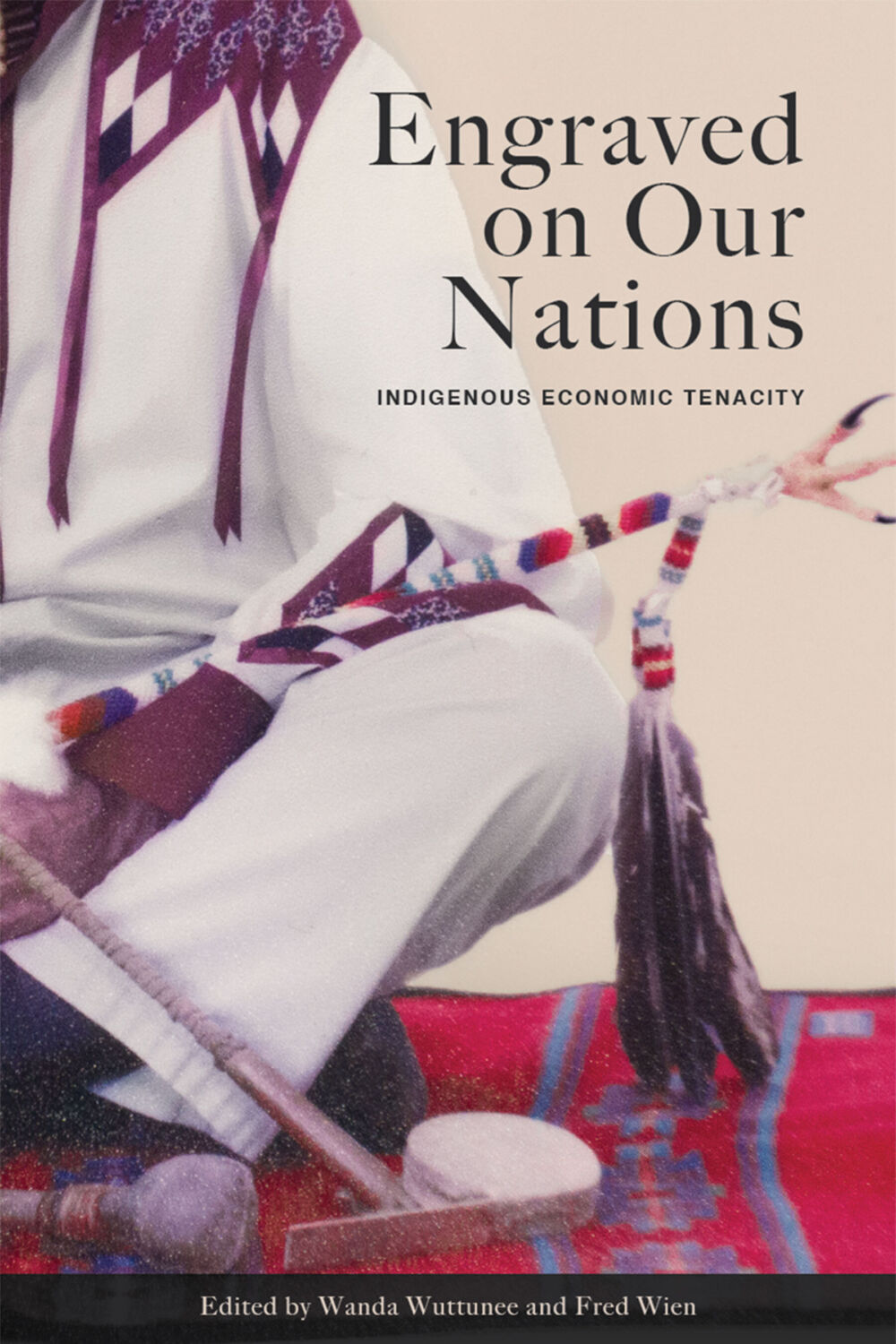

"Developing and supporting Indigenous economies require innovation, creativity, perseverance, and a willingness to see Indigenous nations, peoples, and individuals as economic actors." Read the following excerpt from David Newhouse's introduction to Engraved on Our Nations: Indigenous Economic Tenacity edited by Wanda Wuttunee and Fred Wien, pages 15–20.

The Change

In the twenty-first century, the idea of Indigenous economies has been established. Indigenous economies are now considered part of larger provincial and Canadian economies and are seen as entities to be developed through Indigenous, provincial, and national efforts. This fundamental change is one that Indigenous leaders have created over the last half century. The 1969 White Paper proposed that Indigenous peoples be assimilated into Canada and that Indigenous peoples’ futures follow a trajectory similar to that of immigrants: social and economic integration. Indigenous peoples rejected this trajectory and with great tenacity advocated for a different future: one based upon self-determination as distinct peoples within the Canadian federation, with restored lands and governments and government support.

The performance of Indigenous economies is now reported on through the National Indigenous Economic Development Board. The board measures economic progress through the Aboriginal Economic Benchmarking project, which uses thirty-one different measures to track social and economic well-being. Indigenous economic effort is now seen as a small but significant aspect of the Canadian economy. It has been estimated that reducing the economic gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples would result in a 1.5 percent increase in the Canadian gross domestic product.

Over the last half century, the old idea that economics and business are not part of Indigenous cultures has waned. Excellent studies have been completed by Frank Tough, a University of Saskatchewan professor who wrote an economic history of Native people in northern Manitoba; Rolf Knight of the University of British Columbia, who wrote a history of British Columbia Indians in the labour force around the turn of the century; Sarah Carter, who documented the trials and tribulations of prairie Indian farmers in the last century; Fred Wien of Dalhousie University, who wrote of the economic history of the Mi’kmaq in Nova Scotia; and Douglas Elias, who wrote a history of Aboriginal economic development. Wanda Wuttunee of the University of Manitoba has written of the growth of an Indigenous small business sector as well as on Indigenous community economic decision-making processes. The Journal of Aboriginal Economic Development, published by the Canadian Association of Native Development Officers (Cando) since 1999, is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to exploring various aspects of Indigenous economic development through research and experience. Volume 2 of the 1996 Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples described in full detail the challenges relating to land, resources, and economic development. These works are part of the economic history and life of Indigenous peoples. They are a start in our journey to understand aspects of Indigenous history as well as helping to inform future development efforts.

There is now a vigorous critical debate among Indigenous scholars about the nature of Indigenous economies and the course that Indigenous economic development ought to follow. I have described what I call “red capitalism”; Robert Miller uses the term “reservation capitalism”; Duane Champagne calls it “tribal capitalism”; and Wanda Wuttunee uses the term “community capitalism.” Clifford Gordon Atleo wonders whether resistance to Western capitalism is indeed futile. Elizabeth Rata writes of “neotribal capitalism” to describe the emergence of revitalized Maori economies in New Zealand.

The last half decade has also seen the development of an infrastructure of institutions whose purpose is to further Indigenous economic development: Aboriginal Financial Institutes facilitate access to capital; the Centre for First Nations Governance supports effective governance; the National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association assists businesses, including community-based social enterprises; various business-support organizations such as the Indigenous Business and Investment Council, and the Council for the Advancement of Native Development Officers (Cando), which offers a certificate program for development officers working in Indigenous communities. Aboriginal Chambers of Commerce have emerged in several Canadian cities. Indigenous economic development corporations have become a common feature of Indigenous development. Cape Breton University has established the Purdy Crawford Chair in Aboriginal Business Studies to focus research on how to foster successful Aboriginal businesses. The National Consortium for Indigenous Economic Development, an initiative at the University of Victoria, assists Indigenous peoples in developing their own economies and their own approaches to economic self-sufficiency, sustainability, and success. The Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, an organization of Indigenous businesses, describes its mission as promoting, strengthening, and enhancing a diverse and prosperous Indigenous economy.

Robert Anderson, University of Regina, and his colleagues at the First Nations University argue that there is an Indigenous approach to economic development. This approach is “predominately a collective one centred on [the] First Nation or community.” The development objectives, they outline, are directed to “attaining economic self-sufficiency as [a] necessary condition for the preservation and strengthening of communities,” exercising “control over activities on traditional lands,” improving the socio-economic circumstances of Aboriginal peoples, and “strengthening traditional culture, values and languages and the reflecting of the same in development activities.”

Anderson describes three sets of activities that are the basis of development for Indigenous nations and communities:

1. creating and operating businesses that can compete profitably over the long run in the global economy in order to exercise control over activities on traditional lands; building an economy necessary to preserve and strengthen communities and improve socio-economic conditions;

2. forming alliances and joint ventures among themselves and with non-Aboriginal peoples to create businesses that can compete profitably in the global economy; and

3. building capacity for economic development through

iv. education, training, and institution building; and

v. the realization of Treaty and Aboriginal rights to lands and resources.

Indigenous Entrepreneurs

While many communities are pursuing collective strategies, there has also been a rapid growth in individual entrepreneurs starting businesses both on- and off-reserve. During the 1970s and early 1980s, organizations like the National Indian Brotherhood (now the Assembly of First Nations) “warned against promoting private enterprise at the expense of the entire community.” Rochelle Coté reports that “Indigenous entrepreneurship has grown at a rate five to nine times the pace of the general population in Canada,” citing reports from the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business and Statistics Canada. The Conference Board of Canada in 2020 found a similar rise in Indigenous entrepreneurship as well as the emergence of an infrastructure of institutions intended to support further growth and success of Indigenous entrepreneurs. Both collectively and individually owned enterprises are now important aspects of Indigenous economic development strategies and efforts.

In a report on First Nations Small Business for the First Nations Governance Centre, Warren Weir concludes: “Aboriginal small business is a relatively new and interesting growth industry in Canada. And creative, independent, committed, culturally astute, and hard-working Aboriginal entrepreneurs are adding value to the Canadian economy, while making a difference to them individually, as well as contributing to their families and communities . . . an entrepreneurial spirit is alive, well, and prospering in Aboriginal communities located across Canada."

Indigenous economic development has emerged as a complex area as communities and individuals navigate the territory defined by Indigenous cultural values, mainstream business and economic values and practices, emerging and new areas of business, as well as new ways of doing business in a diverse Canadian economy. Developing and supporting Indigenous economies require innovation, creativity, perseverance, and a willingness to see Indigenous nations, peoples, and individuals as economic actors. The fundamental change that has occurred over the last half century is a willingness to frame Indigenous economic development as being as foundational to Indigenous self- determination as Indigenous self-government is.

A strategy set out forty years ago and pursued diligently and tenaciously by Indigenous leaders has provided a foundation for the rebuilding of Indigenous nations and economies. It is remarkable what can be achieved with determination and tenacity.

Engraved on Our Nations is available for pre-order now.

Engraved on Our Nations

Indigenous Economic Tenacity

Wanda Wuttunee (Editor), Fred Wien (Editor)

This first-of-its-kind collection shares stories not only of entrepreneurial excellence and persistence but of savvy leadership, innovation, and reciprocity, providing hope to Indigenous business leaders, youth, and elected officials working on the front lines to improve economic conditions and achieve “a good life” for their communities.

Posted by U of M Press

February 14, 2024

Categorized as Excerpt

Summer Reading Sale! Bead Talk: Excerpt