An excerpt from Brittany Luby’s Dammed

The Politics of Loss and Survival in Anishinaabe Territory

As part of the University Press Week 2020 Blog Tour

When I close my eyes, I can still see the place of my birth: Lake of the Woods.

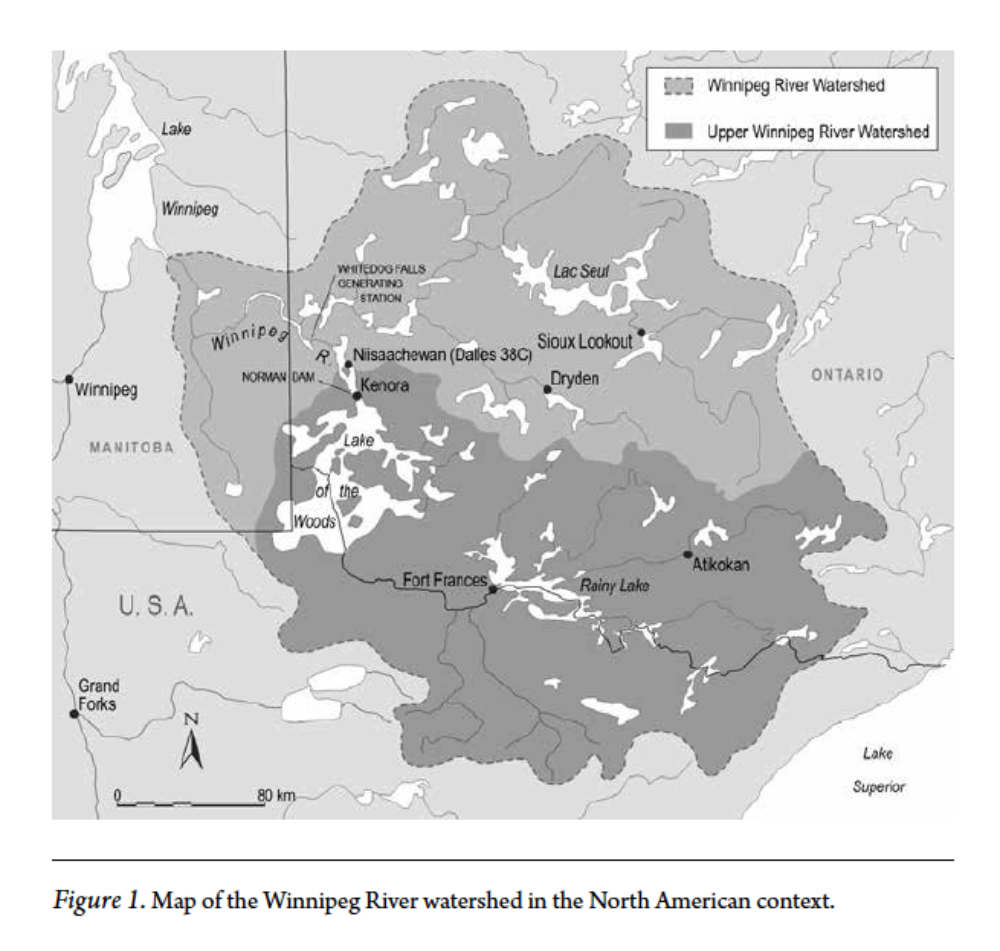

This place is located about 180 kilometres east of the longitudinal centre of what is now known as Canada. It straddles three colonial borders, laying claim to parts of Ontario, Manitoba, and Minnesota. Kenora, my natal home, is at the north shore of Lake of the Woods. It is known for its jagged granite shoreline. It is known for islands of varying size, memorialized in verse as “jade-like gems.” “Jade” is a testament to the jack pine, birch, and poplar that somehow thrive on these rocky outcroppings.

Kenora is most famous for its waterways: Lake of the Woods drains into the Winnipeg River and flows north toward Lake Winnipeg, Nelson River, and eventually Hudson Bay. Water is the lifeblood of Kenora’s economy. It is by water that my ancestors, the Anishinabeg, inhabited this place.

Controversy dominates the story of our origins. Place names suggest that the Anishinabeg originated here—or at least seventy kilometres northwest at Manitou Ahbee (Where the Creator Sits). It is likely that Gitchie Manitou (the Great Creator) envisaged humans there.

First Man, perhaps travelling by foot, made his way to Lake of the Woods, where he learned to fish, to trap, and to harvest manomin (wild rice). Archaeological evidence suggests that Indigenous Peoples have occupied Lake of the Woods since approximately 8,500–7,000 BCE, having followed the retreat of the Wisconsin glacier.

Alternative accounts suggest that the Anishinabeg migrated to northwestern Ontario from “somewhere along the shores of the Great Salt Water [Atlantic Ocean] in the East” around 800 ACE. Edward Benton-Banai, an Anishinaabe cultural educator, suggests that my ancestors moved in search of manomin. Manomin is a complex carbohydrate that flourished locally before the postwar boom in dam construction.

The Kenora Centennial Committee also suggests that the Anishinabeg migrated to Lake of the Woods, but unlike Benton-Banai the committee does not date this migration. It suggests that the Anishinabeg moved to Lake of the Woods “as the white man displaced the Indians in the East.” The committee further argues that the Anishinabeg displaced other Indigenous groups, becoming the primary occupants of Lake of the Woods by 1800. Other authors suggest that the Haudenosaunee Confederacy pushed the Anishinabeg northward during the Beaver Wars. The Anishinabeg, in turn, violently displaced the Nehiyawak (Cree) and warred with the Dakota (Sioux) for occupancy of Lake of the Woods.

However my ancestors arrived—whether by divine intervention, by foot as the glaciers retreated, or by canoe in search of aquatic plants or new land— what is certain is that Lake of the Woods and its outflow channels provided sustenance from time immemorial. Each of these otherwise conflicting origin stories reveals that the Anishinabeg lived by and relied on the water.

By the 1820s, my paternal ancestors—associated with what is now known as Dalles 38C Indian Reserve—occupied a territory that extended roughly from Rough Rock Lake (near present-day Minaki, Ontario) in the north to Muskeg Bay (near present-day Warroad, Minnesota) in the south. James Redsky notes that “some Indians reported there would be other Ojibways who lived in the area as far south as Kasakas-kaw-chimakak (Leech Lake, Minnesota) and as far west…eventually as the Saskatchewan River.”

It is unclear during which years the Ojibway (who form part of the Anishinaabe Nation) occupied this territory. We do know, however, that the Anishinabeg migrated between the north shore of Lake of the Woods and what would become Warroad, Minnesota, in the early 1800s since Redsky notes that Mis-quona-queb, an Anishinaabe leader, lived “at the entrance of the Winnipeg River” for a time and married a woman from Warroad.

In this book, I explore the effects of hydroelectric development within this area of the Winnipeg River watershed from Rough Rock Lake to Muskeg Bay. By sharing an Anishinaabe perspective on hydroelectric development, Dammed challenges popular accounts of Canadian life after 1945. Canadians are often taught that the federal government took an increasing interest in economic development and social welfare in the postwar era, improving the working and living standards of many.

This book is a stark reminder that the benefits of large-scale infrastructure projects and their environmental impacts were (and are) divided inequitably in Canada. The dividing line was (and is) highly racialized.

Long before dams were built along its shores, Lake of the Woods, “with its thousands of miles of irregular shoreline, provide[d] ideal spawning ground for the propagation of all sorts of fish.” For generations, these fish nourished my family.

For example, I was told stories about Chief Kawitaskung (my paternal great-great-great-great grandfather, c. 1820–1914), who netted whitefish in the fall, consumed walleye during the cold of winter, and ate northern pike during the spring. We believe that pike tastes the best when the water is cold and its flesh is firm. During the summer, traders’ accounts suggest, Kawitaskung might have feasted on sturgeon. His wife, Jane Lindsay (birthdate unknown–c. 1916), taught Ogimaamaashiik (my paternal greatgreat- grandmother, 1885–1974) how to prepare these fish. Ogimaamaashiik roasted egg sacs from sturgeon like sausages and simmered whitefish bouillon.

Times changed. Ogimaamaashiik became known as Matilda Martin. But fish remained an essential component of our family diet. By the time of my father’s birth in 1958, fishing provided Anishinaabe families with opportunities to work for pay in the tourist industry. My dad, Allan Luby (Ogemah), led American tourists to prime fishing locations on the Winnipeg River in exchange for spending money. Later, wearing goggles, he plumbed the depths of the river, searching for lost fishing tackle to incorporate into his own collection while continuing to fish for home consumption. Although fish provided sustenance for generations of Anishinaabe families, including my own, physicians working in and around Kenora had recommended that Anishinaabe families not consume fish caught on the Winnipeg River years before my birth (1984). Hydroelectric damming between 1898 and 1958 likely contributed to the increased mercury content of family meals.

Anishinaabe families relied on more than fish. “Sheltered bays yielded thousands of acres of wild rice,” a sacred gift from the Creator to the Anishinabeg. Anishinaabe families defined their territorial boundaries, in part, by manomin growth. Where there was manomin, there were Anishinabeg to harvest it. This was true for many generations. Ogimaamaashiik believed that manomin provided her people with enough energy to carry out their day-to-day activities.

Manomin fuelled trappers—such as her grandfather Kawitaskung—as they hunted for food and furs. She taught her daughter Hazel Martin-McKeever (b. 1927) that manomin was the most effective cure for constipation. Martin-McKeever knew to “put the wild rice, herbs, and lots of water in the big kettle and let it boil and simmer for a long time.” She knew to strain the mixture and drink the remaining fluid. Experience revealed that water begat water.

Family records of what the Anishinabeg ate and how they healed reveal that Lake of the Woods and the Winnipeg River were at the heart of Anishinaabe household economies. Unfortunately, during my father’s growing-up years, manomin cropping on the Winnipeg River collapsed. Elders from Dalles 38C Indian Reserve maintain that the Norman Dam and the Whitedog Falls Generating Station caused water fluctuations that drowned hectare upon hectare of manomin. Today I purchase manomin in small quantities from the grocery store. And I know that Shoal Lake Wild Rice, packaged on Lake of the Woods, includes grains imported from distant lakes.

The collapse of household economies experienced by the Anishinabeg is part of the story of twentieth-century colonization and industrialization in Canada. Natural resources in the Winnipeg River drainage basin drew settlers. Non-Indigenous newcomers moved easily inland along waterways “sheltered by high bluffs and tall forests.” Trappers and fur traders came first. Shortly after Kawitaskung was born, around 1820, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) established a post on Old Fort Island on the Winnipeg River. But the Anishinabeg and the company did not compete for water resources—there were more than enough resources to share. Loggers and gold miners followed. Unlike the trappers and the traders, these newcomers drew water from Lake of the Woods for industrial use.

The sharing of water resources with the Anishinabeg was soon to change. John Kelly of Treaty 3 territory posits that resource sharing decreased sharply in the 1870s. To explain the inequitable division of resources, Kelly employs an analogy of a white man and an Indigenous man sitting on a log. The white man requests “a little place on the log so that he might rest from his awful journey.” So “the Indian willingly shared a piece of his log with the White Man. But the White Man felt like stretching himself and asked for a little more room. The Indian let him have a little more of his log.” The Indigenous man continued to share his resources “like a decent host.” As their relationship developed, “the Indian [became] cold and hungry and [was] barely holding on to the end of the log.” The white man, in contrast, took control over their shared resources. By the 1870s, the white man had pushed the Indigenous man off the log, suggesting “that the Indian could sit on a stump further in the bush.”

This analogy resonates strongly on Lake of the Woods: in 1879, John Mather oversaw the construction of the sawmill for the Keewatin Lumbering and Manufacturing Company (KLM), establishing the first sawmill on the north shore. By 1890, seven large sawmills were operating near Kenora. Lumbering became the primary industry for settler-colonists on Lake of the Woods. To fuel additional development, lumber barons such as Mather sought water power. Between 1893 and 1895, the Keewatin Power Company installed the Norman Dam at the western outlet of Lake of the Woods.

According to some estimates, the dam raised the level of the lake by 0.9 metre to 1.8 metres. When Mather dammed the western outlet, he blocked an artery in the Winnipeg River drainage basin. Flow patterns changed. And, when they changed, Anishinaabe labour practices and household economies—based on and around Lake of the Woods and the Winnipeg River—also changed.

Dammed tells the story of how Anishinaabe families adapted to industrial water fluctuations and their cascading effects, from the signing of Treaty 3 in 1873 to the 1970s, a difficult decade in Anishinaabe history.

It tells of how the Anishinabeg, having forged a land-sharing agreement with the Crown, continued to use Lake of the Woods and the Winnipeg River as in years past—to fish, to harvest manomin, and to travel.

This blog post was written for the University Press Week 2020 Blog Tour; the year’s theme, Raise UP, “highlights the role that the university press community plays in elevating authors, subjects, and whole disciplines, bringing new perspectives, ideas, and voices to readers around the globe.”

Join Brittany and Critical Studies in Native History editor Jarvis Brownlie for a discussion about Dammed and the role of university presses in publishing Indigenous voices on November 10 at 3 pm CST. Register here!

Posted by Brittany Luby

November 9, 2020

Categorized as Excerpt, Author Posts

Tagged anishinaabe, community, history, indigenous, lake of the woods, ontario, raiseup, upweek

A Dedication to Lillian Shirt Mary Riter Hamilton honoured for Remembrance Day