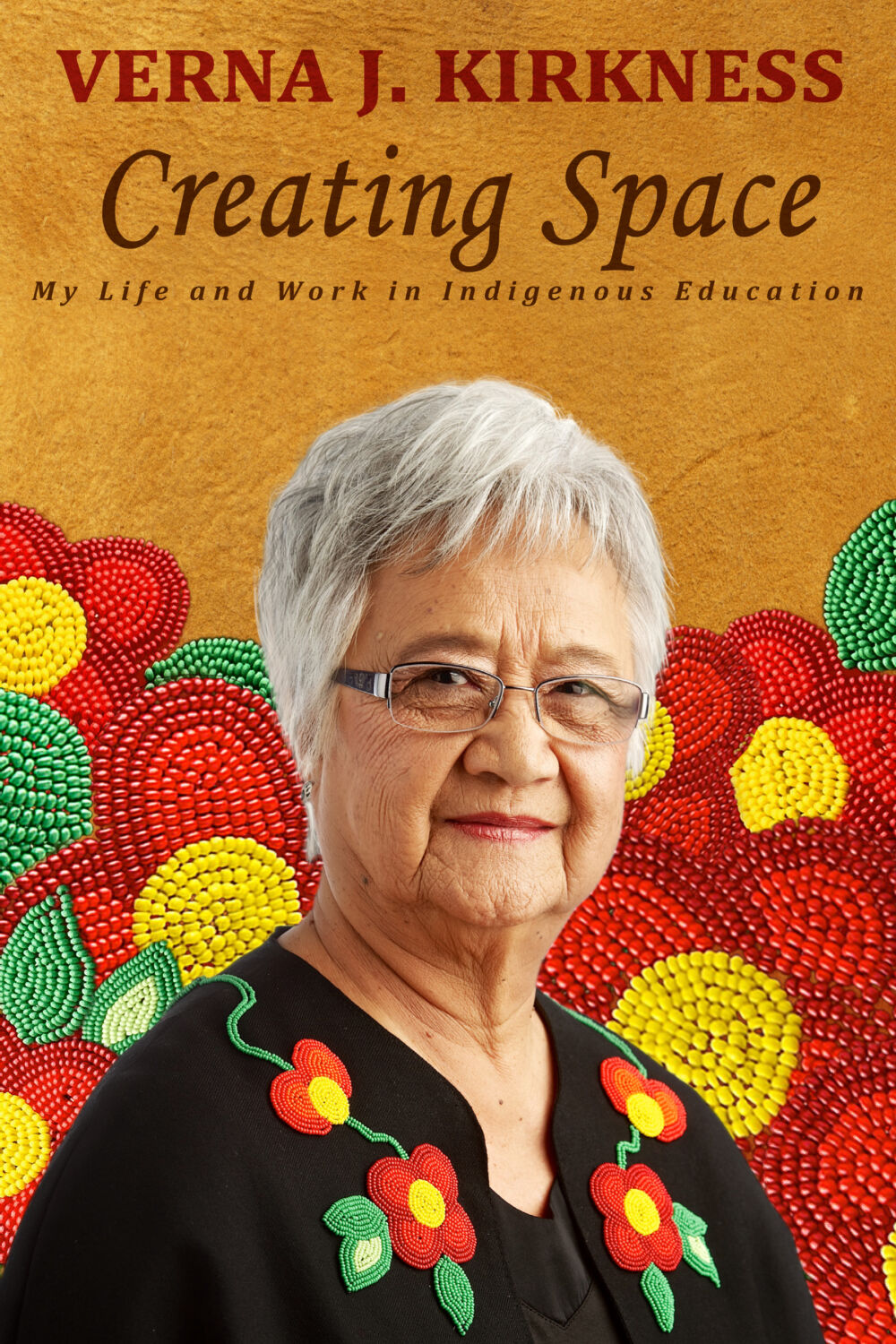

Verna J. Kirkness grew up on the Fisher River Indian reserve in Manitoba. Her childhood dream to be a teacher set her on a lifelong journey in education as a teacher, counsellor, consultant, and professor. For many years she taught and worked throughout the province of Manitoba, including a period in her home community of Fisher River.

Honoured by community and country, Kirkness is a visionary who has inspired, and been inspired by, generations of students. Like a long conversation between friends, Creating Space: My Life and Work in Indigenous Education reveals the challenges and misgivings, the burning questions, the successes and failures that have shaped the life of this extraordinary woman and the history of Aboriginal education in Canada.

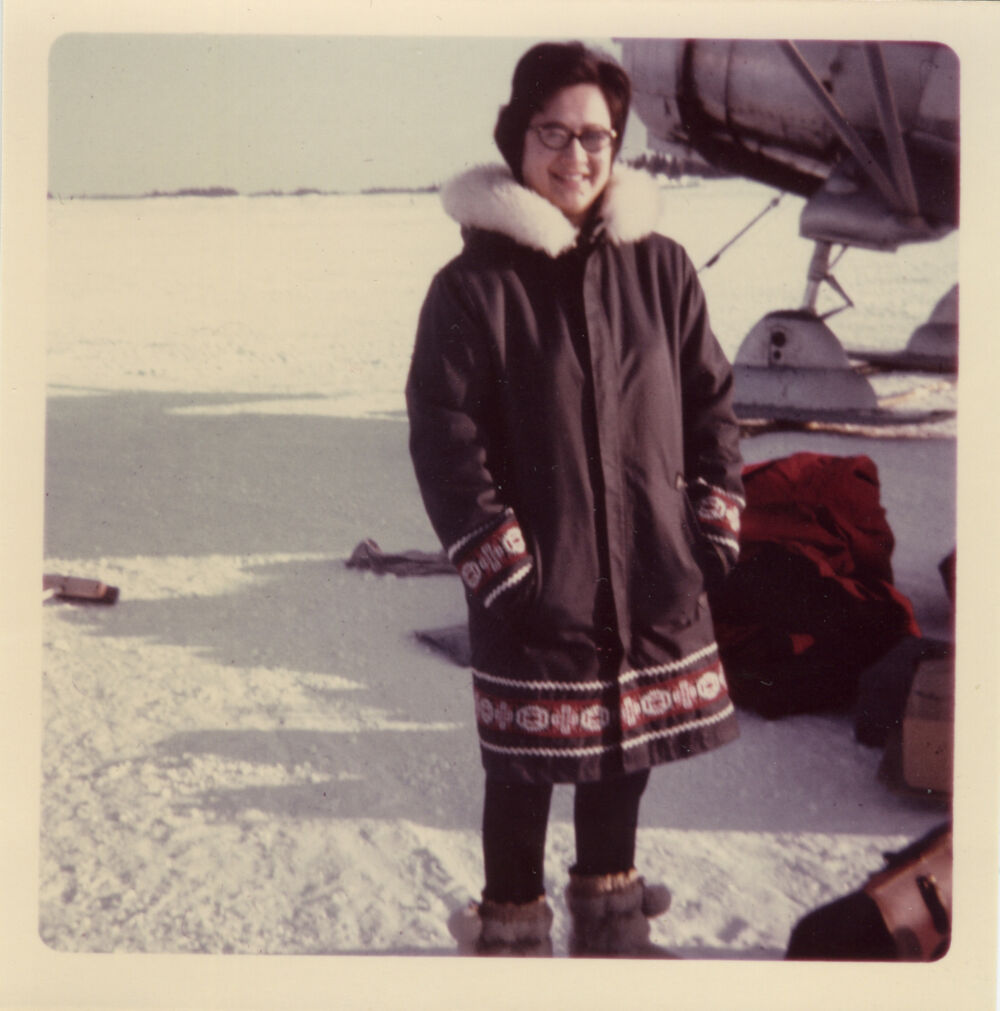

The following excerpt relates the time when she was, at the young age of 32, the Supervisor of Schools for the sprawling Frontier School Division.

*

Frontier School Division covered 288,000 square kilometres, the largest geographical school division in Manitoba. The schools were miles apart, and I did manage to visit each school at least once. I ended up doing a lot of troubleshooting. Of course, I spent more time where I felt teachers were under-performing. I tried to work with those teachers. One of their main problems was discipline. We had much less tolerance in those days with children making noise in the classroom. I still don’t believe that children can learn if they do not listen to what the teacher or fellow students are saying.

I found in several schools that the children were absolutely unruly and the teacher was unable to bring any order to the classroom. During that first year, I convinced a few teachers that they should seek other employment. I did not fire them, which was a good thing, as I may have had a lawsuit on my hands. I was not aware of the provincial rules regarding employment and that I would be expected to provide extensive documentation on a teacher before consideration would be given for his/her release. However, I did not see this job as just looking for trouble spots. I think it was great for those good teachers to have someone who could recognize and acknowledge the work they were doing. I observed many good teachers, but like everything in life it is the problems that get the attention.

Principals and teachers are always wary of any kind of outside authority. I had to be diplomatic in my dealings, especially with the principals, most of whom were male. I always met with them first and talked over generalities regarding the school and sought their guidance as to problems I should be aware of, including the physical condition of the school.

I clearly remember one case where I had spent a few days at one of the larger schools that I regarded as one of the better schools. I thought I had completed my visit to the satisfaction of the principal, since prior to leaving I had met with him to discuss my evaluation of the school, which was also my practice. I went to the office the next morning to find that the principal had called in a complaint to my immediate superior, Abe Bergen, about my visit. Abe and I discussed the matter. I can’t recall the nature of the complaint, but Abe thought it would be a good idea if he visited the principal. I opposed his suggestion and told him if he expected me to do my job, he would have to let me handle it. So back I went to see the principal, about a three-hour drive away. I believe he was quite surprised to see me and not the big boss. We discussed his call and complaint. Nothing further came of it and subsequent visits went well.

I felt that the principal resented me because he was not comfortable with a woman supervising him. It is strange, but I never felt this in any way had to do with the fact that I was a Native or that I did not possess a university education. Actually, I do not think that many people were aware of my educational status.

Two additional supervisors were hired by Frontier School Division the following year. That eased my load considerably, as now I had about sixty-five teachers and principals to oversee and the physical area was divided into three. There were times when two or three of us visited the same school at the same time, so it was not a rigid division. Working together in the bigger schools enabled us to compare findings.

Frontier had one residential high school in Cranberry Portage. They turned an old army base into this school for northern students, many of whom were Métis. It housed around 200 and had a staff that included administrators, teachers, and support staff. Most of the schools in Frontier School Division only went up to grade eight. This was a wonderful opportunity for Métis children to finally have the opportunity to complete high school.

As supervisors we did not have a formal role in Frontier Collegiate, as it came to be known. However, because I am Native, the administration thought it would be a good idea for me to visit the students in the school and talk to them about the importance of education.

At a recent luncheon in Winnipeg celebrating role models, Laara Fitznor mentioned that she had been a student at my presentation at Frontier Collegiate around 1968 and was in awe of the fact that here was a Native woman “who had made it,” so to speak. She said I was her role model from that time on. Laara, herself a successful Métis woman, has a PhD from the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISIE) in Toronto and is now an associate professor in the Faculty of Education at the University of Manitoba.

Just recently, I had the privilege of meeting the now famous Tomson Highway, who was a writer-in-residence at the University of Manitoba and an alumnus of the university. He is now nearing sixty, a successful pianist, author, and playwright known internationally. Originally from Brochet, Manitoba, and a residential school product, he has done a lot to raise the consciousness of all people about Aboriginal people. He acknowledged me at the gathering, saying that I was one of the early pioneers in the field of Aboriginal education that paved the way for others to follow.

It is interesting to note that Frontier Collegiate has not had any of the adverse publicity that the residential schools that were run by the federal Department of Indian Affairs has had. In fact, Frontier Collegiate is still in existence today and is continuing to be an invaluable asset for Métis students.

While I was with Frontier School Division, trying to be of assistance in providing a meaningful education for northern students, most of whom were of Native ancestry, I became aware of a number of problems.

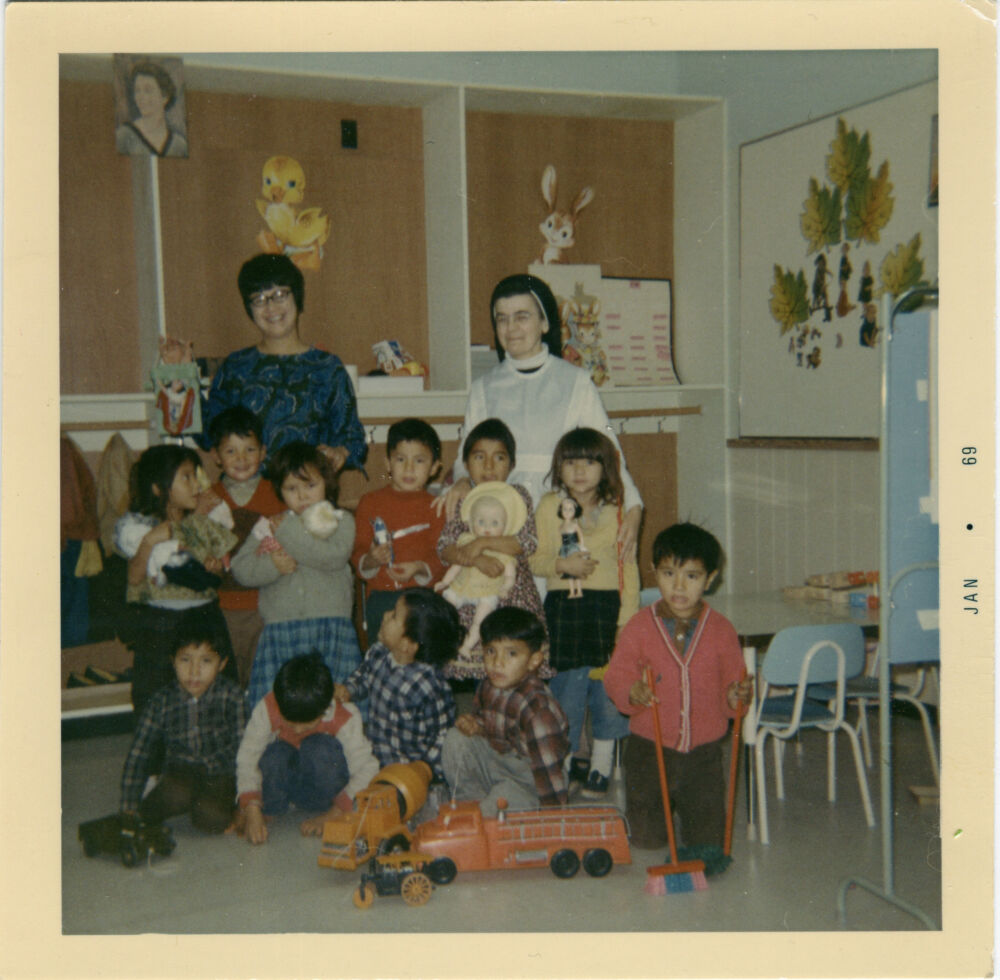

First, there were several schools that had too many students for one teacher to handle. I was aware that Indian Affairs schools did have teacher aides to assist the teachers in their work. As I mentioned earlier, there were two one-room schools in Norway House to serve the non-Native and Métis students. I found the South school had about forty students. I decided to ask Mr. Bergen if we could hire a teacher’s aide for that school.

In those days, the only quick communication with the south was by two-way radio. Because I considered this a serious situation that I wanted to resolve while I was at Norway House, I dealt with the request by two-way radio phone. As it turned out, this was a good approach because, once again, everyone in the north who had a radio could hear the conversation—I knew it and so did the administrator at the other end of the conversation.

I received approval and hired a young Cree woman with a partial high school education. From then on it became a common practice to hire teacher aides in the division. The aides were expected to be in the classrooms assisting the children who had limited English or had problems in reading, math, or other areas.

From my Indian Affairs experience, I was aware that they had training for teachers’ aides every summer; I had been a resource person for a number of these sessions.

I have to share a funny story related to the idea of hiring paraprofessionals to assist teachers. I remember being involved in a great debate with Indian Affairs personnel about what they should be called. Should they be teacher assistants, paraprofessionals, or what? To lighten the discussion, I suggested that they be called “Band-Aides.” Fortunately, that caused a laugh as was intended. They did come to be known as teachers’ aides. I find it ironic that it took other school divisions years to follow this practice and now many provincial school divisions have adopted the practice of hiring teachers’ aides.

About Manitoba 150 Excerpts

May 2020 marks Manitoba’s 150 anniversary as a province of Canada. The Manitoba Act was passed by the Parliament of Canada and received Royal Assent on May 12, 1870, creating the Province of Manitoba. To celebrate, throughout the year we will be posting excerpts from some of our titles that touch on Manitoba’s history, people, and cultures.

Posted by U of M Press

August 24, 2020

Categorized as Excerpt, MB 150

Tagged community, cree, education, history, indigenous, indigenous education, manitoba, manitoba 150, mb 150, policy

Isabelle St-Amand on Indigenous cinema and media Speaking Silences and Divulging Secrets