On July 3 1912, fifteen days after departing from Antwerp, Belgium, the Canadian Pacific steamship Lake Michigan docked in Quebec City. The steamship’s manifest classified 1,017 of its 1131 passengers, including 157 Jews, as third class or steerage, immigrants whose entry into Canada depended upon an interview with immigration officers to determine if they were admissible under the Immigration Act.

Miriam Epstein, aged 23, who was accompanied by her 21-year-old brother in law Leib, a cap maker, and her two children Israel, aged 11/2 and Feige, aged 3 months, informed immigration officers that they were joining Miriam’s husband Moishe who had immigrated to Canada in June, 1911, settled in Winnipeg and found employment as a tinsmith.

After showing immigration officers that they possessed train tickets, $31—more than the $25 Leib needed to demonstrate that he was self-sufficient—and passing a medical examination they boarded a Canadian Pacific Railway train for Winnipeg. Arriving at the CPR station they were met by Moishe who took them to their new home on Manitoba Avenue in the city’s North End.

The Epstein’s were part of a wave of approximately 7,300 Jewish immigrants from the Pale of Settlement in Tsarist Russia who settled in Winnipeg between 1882-1914. Fleeing destitution, state persecution and sporadic but increasingly murderous pogroms they came to Canada as refugees seeking safety and an opportunity to find employment or establish a small business to support themselves and offer their children a better life.

Like the Epsteins, the overwhelming majority of Jewish immigrants settled in the North End, Winnipeg’s “foreign quarter.” The Jewish community they established contained elements of continuity and change. They first established synagogues, religious observance provided spiritual sustenance and an institutional base that enabled them to maintain their identities and adapt to an alien and often hostile British Canadian society.

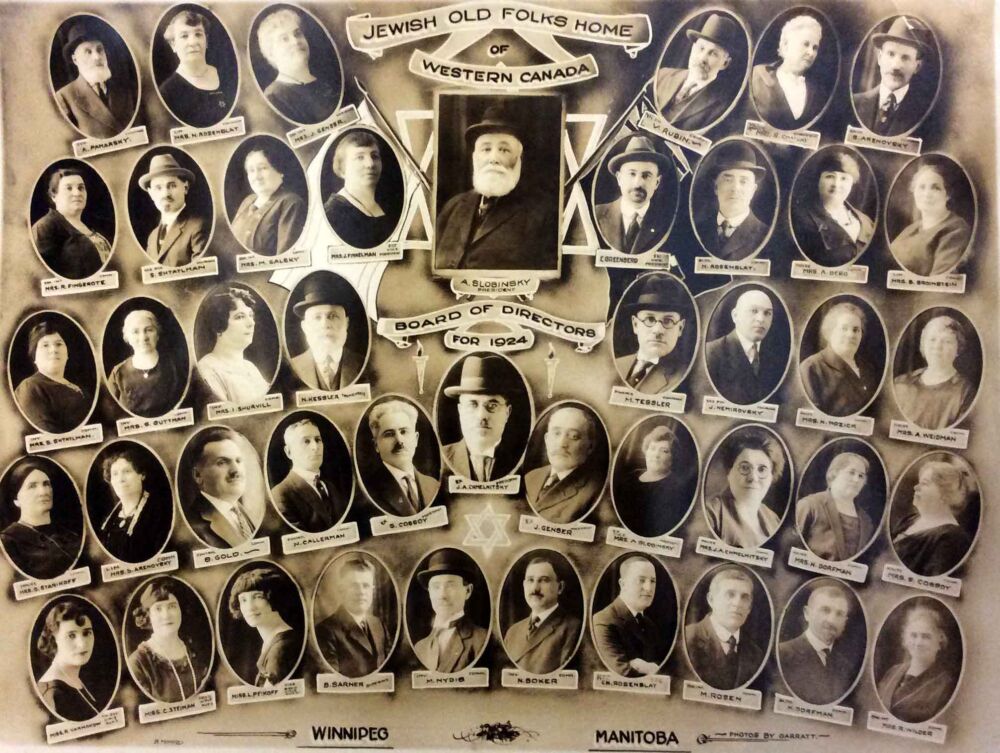

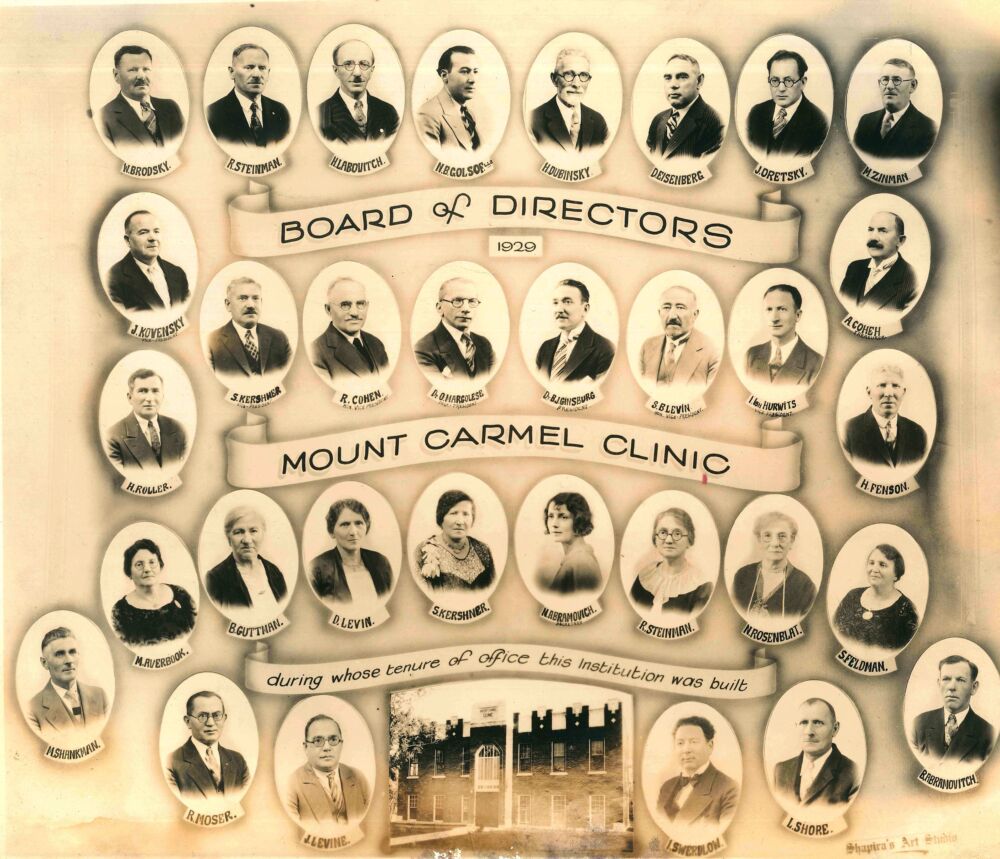

But instead of uniting the Jewish community, religious observance led to bitter disputes among different synagogues that undermined efforts to provide assistance to its vulnerable members. Having experienced the diverse social and political manifestations of an intense debate in the Pale of Settlement over Jewish emancipation they shifted community decision-making to the common ground of the public sphere, establishing a system of social welfare based on egalitarian principles of democracy and communal solidarity.

Communal Solidarity is the culmination of a long-standing interest in the process of settlement, the integration of immigrants into Canadian society. Immigrants have built communities that have incorporated elements of their pre-immigration lives but also taken advantage of Canada’s liberal democratic freedoms to establish new forms of communal life.

This study of the formation of Winnipeg’s Jewish community examines the achievements of a remarkable generation of men and of women; their role in process of Jewish immigration and contributions to communal life have not been given the recognition they deserve.

Certainly, as the Epstein family’s experience demonstrates the reunification of Jewish families in Canada was only possible because of the courage and resourcefulness of women. In addition to supporting themselves and their children until their husbands were able to send them tickets and money for travel expenses they had to complete a challenging journey. Because passports were difficult and expensive to obtain, most Jewish women and their children left Russia illegally. Guided by smugglers, they crossed the Russian border clandestinely, typically arriving in an Austro-Hungarian town at the eastern terminus of a railway network that extended westward to European ports.

Rarely fluent in the languages spoken in transit countries, Jewish women had to contend with numerous government officials, negotiate currency exchanges, and find food and accommodation when making train connections or at a port waiting to board a steamship for Canada. Like Miriam Epstein, a male sibling or relative accompanied some women but many travelled alone with their children.

Combing through the collections of the numerous archives and libraries I was repeatedly struck by the important contribution women made to establishing, managing and supporting the Jewish community’s system of social welfare. Although it was often difficult to document I hope I was able to demonstrate that despite the constraints of traditional gender roles countless women became communal activists who often led rather than followed men.

In addition to documenting the organizational histories of the societies, institutions and organizations Jewish men and women created, this study explores how their beliefs about communal solidarity shaped both their understanding of community life and the way decisions should be made about their collective future. It is also a testimonial to the determination of innumerable communal activists – since so many records, particularly of mutual aid societies, have been lost, too few of them could be identified – to build a Jewish community which not only assumed collective responsibility for the welfare of each of its members, but also contributed to international efforts to aid their brethren in Eastern Europe.

Their debates over who had the authority to act in the name of the Jewish community, networks of Jewish notables or democratically elected communal activists, and how they resolved conflicts over communal governance provide insight into the complex dynamics of the settlement and integration of Jewish immigrants in Canada’s third largest city. Above all, Communal Solidarity seeks to honour the dedication, resourcefulness and organizational enterprise of the Jewish immigrants who self-confidently created a public sphere to build the better world they dreamed of when they made the momentous decision to emigrate.

Posted by Arthur Ross

April 30, 2019

Categorized as Author Posts

Tagged community, history, immigration, jewish, manitoba, migration, mutual aid, mutual aid society, winnipeg

Arthur Ross in Winnipeg Structures of Indifference recognized!