“Asian Canadian” remains a fluid and changing category of identity because Asian Canadian experiences are plural—global, intergenerational, cross-cultural. Yet the anti-Asian racism manifest today through the politicization of COVID-19 mirrors white Canada’s anti-Asian hate of forty years, sixty years, eighty years, a hundred years ago. Read the following excerpt from Angie Wong’s forthcoming book Laughing Back at Empire: The Grassroots Activism of The Asianadian Magazine, 1978–1985.

THEN AND NOW:

The Asianadian and the Radical Spirit of Community Care

“Asian Canadian” remains a fluid and changing category of identity because Asian Canadian experiences are plural—global, intergenerational, cross-cultural. Yet the anti-Asian racism manifest today through the politicization of COVID-19 eerily (though not surprisingly) mirrors white Canada’s anti-Asian hate of forty years, sixty years, eighty years, a hundred years ago. I came across The Asianadian magazine when I was a graduate student at York University, long before the COVID-19 pandemic. Sadly, I had my unfair share of racist encounters with white and white-passing professors, university administrators, and colleagues, an all-too-common experience for students of colour, especially women, Canadian-born or otherwise. I was judged for being a Chinese woman and made to feel responsible for all those restrictive and negative stereotypes and expectations that the Western gaze associates with being Chinese and a woman.

To now see the full effects of racist violence—the physical assault and murder of women who look like me and older Asian adults—as COVID-19 is racialized by Western political leaders who describe it as the “China virus” and “kung flu” and blame it on a laboratory leak in Wuhan, China, has shaken me to the core. I naïvely did not believe that my generation would face such racial adversity, not after the Chinese head tax, South Asian exclusion, and the internment of Japanese Canadians, not after the government apologized for all of that. I believed we had learned from the past. I had good reason to believe we had made progress; Richard Fung, video artist, writer, and an editorial member of The Asianadian, even told me that he thought ignorance “died” in the 1980s. Yet we found ourselves here again, facing another wave of Canadian anti-Asian racism, which is not so separate from the anti-Asian hate of the United States.

Then, during the pandemic, musician, poet, Terry Watada, another Asianadian editorial member, penned “Found Poem.” It helps me see that those wretched racist encounters were the beginnings of my own extensive reflection and practice in antiracism and coalition building— the primary ideas espoused by The Asianadian magazine and collective. It also helped me realize that the good fight is never won. This book is not about my personal journey or experiences with overcoming racism, though it is partially inspired by the ways in which the cofounders and members of The Asianadian welcomed me into the collective when I approached them about this work.

[…]

Pages 10 – 12

The Asianadian: An Asian Canadian Magazine, 1978–85

The Asianadian: An Asian Canadian Magazine was the first pan-Asian Canadian social justice magazine. As a quarterly publication that ran from 1978 to 1985, The Asianadian is a rather concise archive of six volumes and twenty-four issues. While each issue from cover to cover contains on average thirty-three pages, it hosted a remarkable number of recurring departments, featured articles, community directories, artworks and photographs, advertisements, and public submissions. During its seven-year run, The Asianadian presented the works of over 200 Asian Canadian artists, musicians, writers, and scholars. Its editorial collective underwent dynamic changes throughout the years, but the radical antiracist spirit of its cofounders and major contributing editors persisted through a remarkable period of Asian Canadian social-justice coalition building, community organizing, and cultural production. The magazine was among the first Asian Canadian publications to be expressly antiracist, antisexist, and antihomophobic in its style and agenda, and it hosted nation-wide dialogues on social, political, and cultural struggles that concerned Asians in Canada at the time. Similar to struggles today, they involved overcoming racism and sexism, combatting white supremacy, finding pride in community, and exercising Asian Canadian agency and self-determination. Without theory, they tested the boundaries of traditions from Asia and in Canada, especially as the country moved towards adopting multiculturalism and a bilingual and bicultural colonial foundation.

Most significant, it was the first national platform for Asian Canadian writers, artists, musicians, and scholars—many of whom were young, activists, postgraduates, and aspiring filmmakers working at both the centre and peripheries of Asian Canadian social justice with The Asianadian and other related organizations, such as the emergent Chinese Canadian National Council. As the first of its kind, The Asianadian editorial the collective offered newness in a different way, through artistic, musical, poetic, and political expressions that mobilized community care and produced real-life change. Its social justice work existed within a minor intellectual and cultural milieu established by other small magazines that were active in the twentieth century, such as The New Canadian, Fireweed, and Rikka. Alongside these smaller periodicals, the first anthology of Chinese and Japanese Canadian writing, Inalienable Rice: A Chinese and Japanese Canadian Anthology, was published in 1979. This era of awakening saw people organizing collectively to voice the ways in which the state enforced racist and sexist policies of exclusion against their ancestors, relatives, and other people marginalized on these lands. The Asianadian era was a path-breaking moment in and for Asian Canadian consciousness—one that developed by writing and visualizing resistance and exercising the hybrid capacities of thinking, being, doing Asian, Canadian, and more (paralleling the consciousness raising of their Asian American counterparts). This book is also a celebration because many former editorial members, volunteers, contributors, and collaborators who worked on The Asianadian are still with us today.

The Asianadian editorial collective instigated a significant form of epistemological deconstruction of anti-Asian stereotypes—against women, East Asian countries, patriarchy, food habits—that obtained cultural hegemony under the discursive formations of the Yellow Peril ideology and White Canada Forever movement that was active from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century and is resurgent today. This space of cultural production defied the homogeneity of Western time and its cacophony of colonial signs, through collective laughter and critical creativity. It was a space for enunciating “Asian Canadian” beyond only Asian or Canadian. As postcolonial theorist Homi K. Bhabha writes, “Between the Western sign and its colonial signification there emerges a map of misreading that embarrasses the righteousness of recordation and its certainty of good government. It opens up a space of interpretation and misappropriation that inscribes an ambivalence at the very origins of colonial authority.” The collective contested forms of colonial knowledge by opening a platform to Asian Canadians to interpret and misappropriate the language and ambivalences of settler colonial authority on their own terms, building agency and community. Members of the Asianadian Resource Workshop knew they required pan-Asian Canadian community engagement because they recognized that Asian Canada is made up of culturally unique communities, groups, and individuals. “The narrative of community,” Bhabha writes, “substantializes cultural difference, and constitutes a ‘split-and-double’ form of group identification.” Even the term “Asianadian” evokes singular duality or a hybrid way of being that matched the diversity of the collective’s members (further reviewed in Chapter 4). They produced new ways to wield language that were followed by other contributors to the magazine, generating an idiosyncratic vernacular and style.

Through their cultural production, Asian Canadian writers and artists of this period wrote their experiences into existence and into the fringes of the nation; the magazine was one of the few literary and artistic spaces available for Asian Canadian writers of the time. For instance, one contributor who identifies as Japanese Canadian contributed poetry to Volume 5.4 (Spring 1983) and remembered that The Asianadian was one of the rare publications to which she and other aspiring Asian Canadian writers felt comfortable submitting work. In this space, the instrumentality of language generated clear meanings. As postcolonial feminist scholar Trinh T. Minh-ha asserts, “To write is to communicate, express, witness, impose, instruct, redeem or save—at any rate to mean and to send out an unambiguous message.” Thus, as we shall see in the coming chapters, The Asianadian clearly developed its own hybrid vernacular and creative process that teased out multiple methods for using language, rhetoric, and reference, generating forms of grassroots “play” within extant structures of colonial discourse. Bhabha writes that “these ‘in-between’ spaces provide the terrain for elaborating strategies of selfhood” that are otherwise foreclosed, and thereby “initiate new signs of identity, and innovative sites of collaboration, and contestation, in the act of defining the idea of society itself.” While strategizing to reclaim language under postcolonial dissection beyond theory was an intuitive act of agency and grassroots self-determination, it became an overt goal of the collective. As the first grassroots collective to host conversations about anti-colonialism without the use of theoretical jargon, these organic intellectuals from around the world shared their life experiences across borders as well as a under the transformation of Canadian nationalism, introducing readers to subtly complex ideas related to imperialism and its vehicle of colonization in a critical and accessible manner.

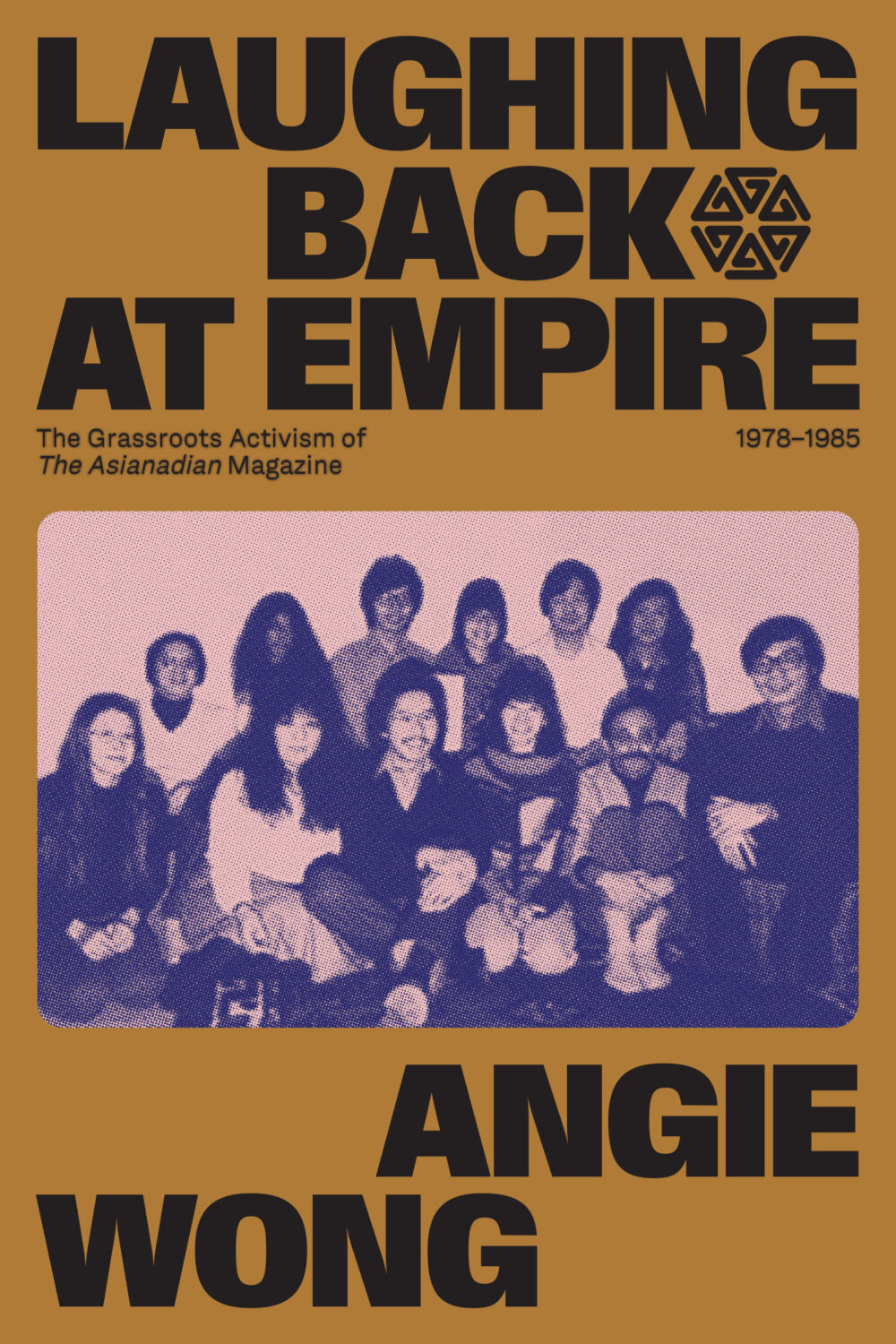

Laughing Back at Empire

The Grassroots Activism of The Asianadian Magazine, 1978–1985

Angie Wong (Author)

Laughing Back at Empire is a groundbreaking examination of The Asianadian, one of Canada’s first anti-racist, anti-sexist, and anti-homophobic magazines. Wong’s work amplifies Asian Canadian voices that speak, shout, and laugh together at empire’s self-congratulatory and exclusionary narratives.

Posted by U of M Press

June 29, 2023

Categorized as Excerpt

Tagged asian canadian, excerpt, history

2023 Awards Season Interview with Robert Coutts, author of Authorized Heritage