The following excerpt is from Letters with Smokie: Blindness and More-than-Human Relations by Rod Michalko and Dan Goodley, pages 21-27:

13TH SEPTEMBER 2020

Congrats!

What a beautiful one-minute advert for your new book! BTW, you look great in the video. I particularly like the blue and gold scarf draped, in a cavalier way, over your shoulders bringing out the beautiful royal blue in your shirt and aquamarine of your eyes. Lovely! Did you get new glasses? Smashing!

We’ve ordered your book. Thanks for the shout-out to Smokie and me, beautiful Dan. However, I must speak for Smokie. If he were alive, he would speak for himself of course, but . . . His question and don’t let it offend you, Smokie—he’s just like that when he uses human language—he says, “WTF! Other Human Questions? What? Are you humans the only ones who can ask questions? So, what am I? Chopped liver? Don’t answer that. I get it; you’re just interested in the human. Start broadening your thinking regarding the human. I, and others like me, have questions too! Namely, who the fuck do you think you are talking about us while ignoring our questions? BTW, thanks for the mention. Between you and me, Dan, I was getting quite sick of dragging Rod around. Forward, Smokie. Right. Left. Not only that, the dude had no idea where he was going. If it wasn’t for me— nothing. Nada. He would have been zero. I made him, Dan. Anyway, enough about me. How are you? If that’s not too human of a question.”

Sorry, Dan. When the Smoke-ster got going on a rant, it was impossible to stop him. Take his words with a grain of salt, and he hasn’t even finished reading your book; he’s only on chapter four.

Brilliant book!

xxx

Rod

13TH OCTOBER 2020

To Smokie; well, Rod, please can you pass this on to him.

Dear Smokie,

It’s one of my main regrets in life that I never got to meet you in the flesh. The thing is, though, that human being that you hung around with (you know, the Canadian athlete, the one who took you in all those bars, the hard man “American Football” player, I think he goes by the name of Rod Michalko), well, he talks about you all the time. And I mean all the time. You, Smokie, are very much part of the stories we tell one another—Rod, Tanya, Rebecca, Ruby, Rosa, me, and many others—and while they might be human stories, they are also full of non-human stories too.

So, I suppose one way of thinking about things would be to say that while we start off with questions of the human, they soon morph, change, and bend into questions about the more-than- human. Truth is, Smokie, I think I already know you because of the tales that Rod and Tanya share about you. And I know it’s not as good as meeting in the flesh (believe me, I am one handsome chap like your good self, and I know we would get on); the stories that are told about you do mean you are very much part and parcel of our world (the human and non-human).

Thanks as always for the provocation. And thank you, sincerely, for being around to permit Rod to come up with that really funny gag about you being a “blind dog.”

Much love,

Dan

1ST NOVEMBER 2020

Hi Dan,

I really have to say I wasn’t expecting you to write back to me, not directly anyway. Every other time someone wanted to say something to me, they told Rod and then he told me. You were the first one that got back to me, right to me. I have to say, I like this better—talking direct like this.

The other thing that happened for the first time was when I told Rod what I thought about your book, he said he would pass it on to you directly from me, word for word. I didn’t think much of it at the time. The truth is, I never thought I could speak to anyone directly except Rod, and I didn’t think anyone else could speak right to me except Rod. That’s why I’m so surprised to hear from you.

This place, this other world, as you humans like to call it, is pretty cool. Got the rest of them with me a few years back, all three of them, so it’s even better. It’s very peaceful and you never get tired no matter how much you run and play. You never get hungry either, no matter how much you eat. Lots of trees, grass, places to swim—love it. Just love it. Sure miss Rod, though—Tanya too. But, I talk to the guy every day. He fills me in on what’s going on, keeps me in the loop. They’re back in Toronto now; always thought they’d get back there one day. But, I guess without us . . .

Anyway, enough about that.

You guys met, I mean you, Rod, and Tanya, you met a long time ago, around 2009, wasn’t it? Wasn’t it someplace in Arizona at one of those conferences they used to go to about disability studies? I was gone for a few years by then, I mean, to that other world place. I sure was touched when Rod told me you read the book he wrote about us. That meant a lot to me—how much you and Rebecca enjoyed that story—it really did. So, you met way back and, as you humans like to say, the rest is history—all disability studies and all friendship. I sure have been enjoying all the stories about this friendship you guys have. I always let Rod know about what I think of the stuff he’s been doing and writing, stuff about this disability studies thing too. But, this is the first time, like I said, that someone other than Rod got back to me directly about disability, so let me tell you more about what I think about what you said.

Like I already told you, I reacted mostly to the title of your book. Rod told me about your book, about some of the chapters and how you were writing about your relationship to disability and all of that. He hasn’t read it all the way through yet, so we haven’t discussed it fully. I’m sure we will as soon as he reads it and I’m sure that Tanya will have something to say about it too.

The thing about your title—_Disability and Other Human Questions_—is the last part, the other human questions part. I get it; there is the question of disability and then there’s other human questions. I’m thinking this means that disability is a human question and that’s what I wrote you about before. My point was that I don’t think disability is strictly a human question and, I don’t know what other human questions you had in mind, but sticking strictly to the human is where you humans make a mistake.

I guided Rod for nearly ten years and, when I say I guided him, I mean everywhere—all around Toronto and then later all around Antigonish, Nova Scotia. We took subways, street- cars, buses together, travelled on trains, planes, and even boats. We did everything together. This sounds like a lot of work to humans. In fact, you humans call us working animals, or even worse, service animals; I hate that name. I loved hanging with Rod, taking him to all the places he wanted to go and even to some places he didn’t. I remember one time in Antigonish, compared to Toronto, it’s really small. They had a summer fair, tiny little midway, food stalls, and the thing I loved best, a barn with all kinds of animals: cows, sheep, horses, you name it, they had it. I love animals, Dan. We went into that barn and the first thing I saw was this big cow. It was in the stall, of course, with a gate. But, there were spaces between the boards of the gate and that cow and we stood there, nose to nose, for a long time getting to know each other. Then, Rod got me going. I didn’t want to, so I took my time. But he always thought he was in charge, so eventually, I let him think that and we moved out of the barn, but I went real slow so I could check out all the other animals. When we got out, Rod gave me one of those vague commands he sometimes did when he wasn’t sure. No way he could have known how to get around the fairground—when to tell me left, right. So, he did what he always did in situations like this, he let me be in charge. Quite honestly, he had no choice. So, what I did is guide him around the fairground, slowing down a little at places where I thought he might get a kick out of the sound, but I kept my eye on that barn. I kept guiding Rod around and around the fairground until I knew he was pretty much lost and then . . . I took him right back to the barn. Rod was great about it. He just laughed, scratched me behind my ears, and told me I was a good boy, and then I laughed and we hung around the barn for a while. Rod was good that way. I guided him where he needed to be and he let me do what I needed to do. Not all of my guide dog friends have blind guys like Rod, that’s for sure.

My point is, Dan, I hung around with a blind guy for most of my life, and blindness, I bet you, like all disabilities, is way more than a human question. That’s why I like what you wrote to me. You said something like while you start off with questions of the human, they soon morph, change, and bend into questions about the more-than-human. Now, this is good stuff. The thing is, I spent my entire life with humans. I was trained to be a guide dog. In the dog world, we call this postgraduate education. Cool, eh. The only thing I’m not sure of is that this difference between human and non-human fits my experience, not exactly. I get how human stories can morph into non-human, but do you think it goes the other way around, too? Sometimes I think human questions, non-hu- man questions, human stories, non-human stories, what’s the difference? There has to be one, I guess, but what is it?

Those are just a few thoughts I was having about what you wrote me, Dan. Rod tells me all about you, Rebecca, Ruby, and Rosa and how you guys are like family. I wish I had met you in the flesh, too, but I really feel I know you from the tales Rod tells about you and, believe me, there’s lots of them. I know you’re right, Dan, we would definitely get on and, you’re also right, we are two handsome chaps. By the way, that blind dog thing—that wasn’t a gag—someone actually said that about me. Fucking humans.

Much love,

Smokie

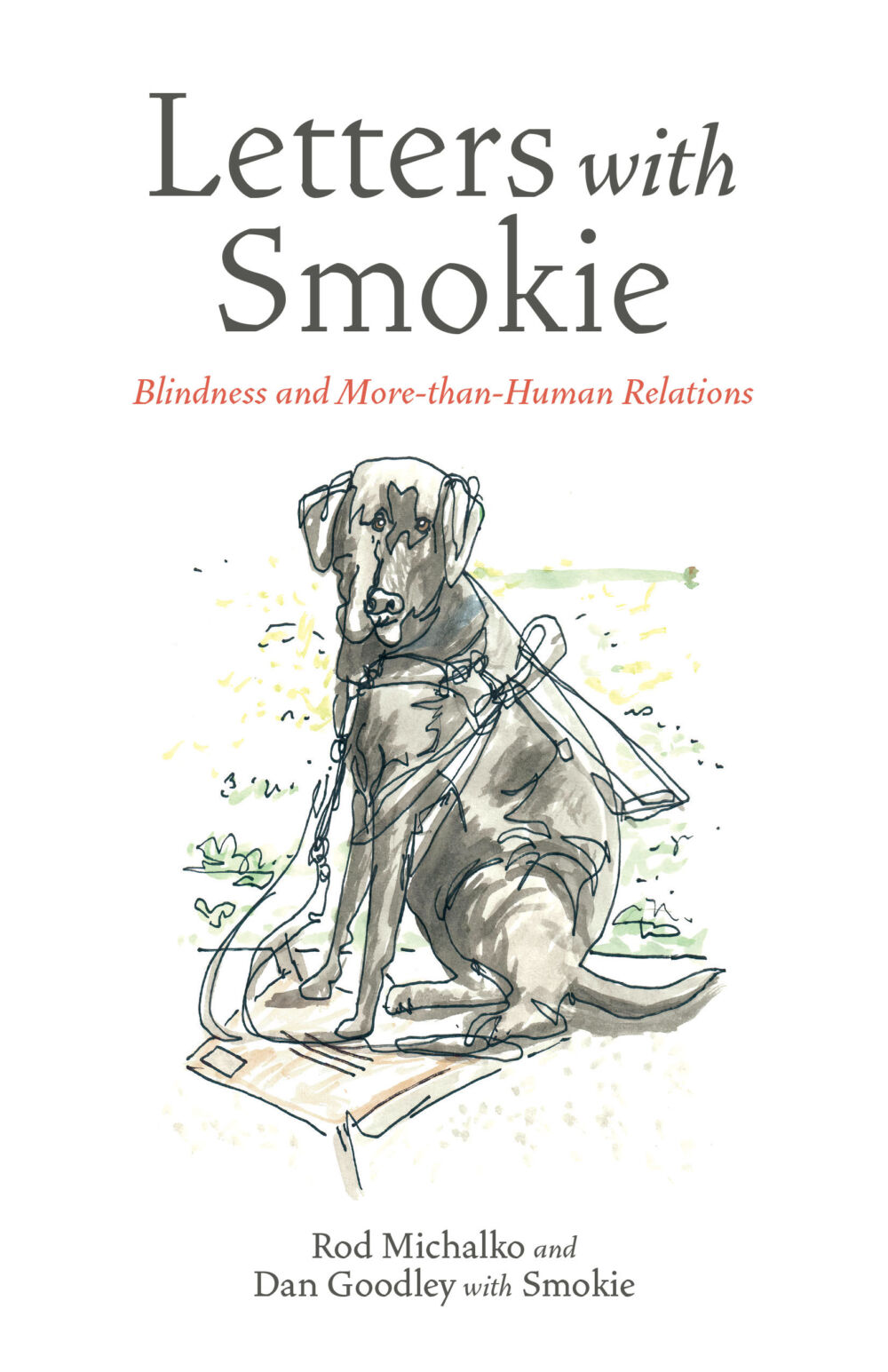

Letters with Smokie

Blindness and More-than-Human Relations

Rod Michalko (Author), Dan Goodley (Author)

Letters with Smokie captures an epistolic exchange between Dan Goodley and Rod Michalko, or rather, Rod Michalko's late guide dog, Smokie. A lively exploration of human-animal relationships and disability as disruption, disturbance, and art, the book offers a refreshing re-evaluation of cultural misunderstandings of disability.

Posted by U of M Press

July 27, 2023

Categorized as Excerpt

Tagged community, disability

Interview with Robert Coutts, author of Authorized Heritage Summer Reading Sale!