Reimagining Warriorhood – A Conversation with Taiaiake Alfred

From Masculindians: Conversations about Indigenous Manhood

Sam McKegney: What then have been the influences of the dominant media-informed stereotypes of Indigenous masculinity—for example, the “bloodthirsty warrior,” the “noble savage,” and the “drunken absentee”?

Taiaiake Alfred: Well, I think that all of those stereotypes were instrumental to someone else’s agenda. For the violence of conquest you needed a violent opponent so you created this image of the Native as violent warrior, the classic horseback opponent. And then you had all of these other things that were created completely out of context, usually. The way to confront that and to defeat it and to recover something meaningful for Natives is to put the image of the Native male back into its proper context, which is in the family.

And so if the image of the Native male is defined in the context of a family with responsibilities to the family—to the parents, to the spouse, to the children (or nephews, nieces, or whatever, or even just youth in general)—if you put the person back into their proper context there are responsibilities that come with that, as opposed to just serving the one responsibility, which is as the foil for white conquest in North America.

So there’s no winning in that one for Natives because, firstly, there’s just no winning in that kind of power struggle, and secondly, if you construct yourself to serve that role, there may some pride in physicality, and so forth, but there’s no living with it because it’s not meant to be lived with; it’s meant to be killed, every single time. They’re images to be slain by the white conqueror. And now that they don’t slay them, most of the time, openly, you know, what’s the role of the Native male? And they haven’t really constructed a role for themselves because they haven’t really been put back into the proper context because the communities are still reeling from the conquest.

So the Native family structure, I think, is the most important thing to foster, because then men will recognize that there’s just as much pride to be taken in a family role as there is in the Hollywood Indian. So right now a lot of these Natives, they still want to live the Hollywood Indian because it’s the only source of pride that they have, the only image that they have. There’s no channel, I guess, for productive masculinity in a productive way. You still constantly reproduce the image of all of those three that you talked about—the absentee, the drunk, the tough guy, the warrior—and those are all anti-family messages. They may be good for the man, maybe, for a short time, but they’re not good overall for the man in the long term. And they’re certainly not good for the family.

And so I think a focus on rebuilding the foundations of Native communities in terms of looking at responsibility to the community, as opposed to living out someone else’s fantasy, is the first thing.

Taiaiake Alfred (Bear Clan, Mohawk) is a Professor of Indigenous Governance at the University of Victoria. Born in Montreal and raised in the Kahnawake Mohawk Territory, he currently lives in Wsanec Nation Territory on the Saanich peninsula. He is the author of dozens of articles, essays, research reports, and stories, as well as three scholarly books: Wasase: Indigenous Pathways of Action and Freedom (Broadview 2005), Peace, Power, Righteousness: An Indigenous Manifesto (Oxford University Press, 1999/2009), and Heeding the Voices of Our Ancestors (Oxford University Press, 1995).

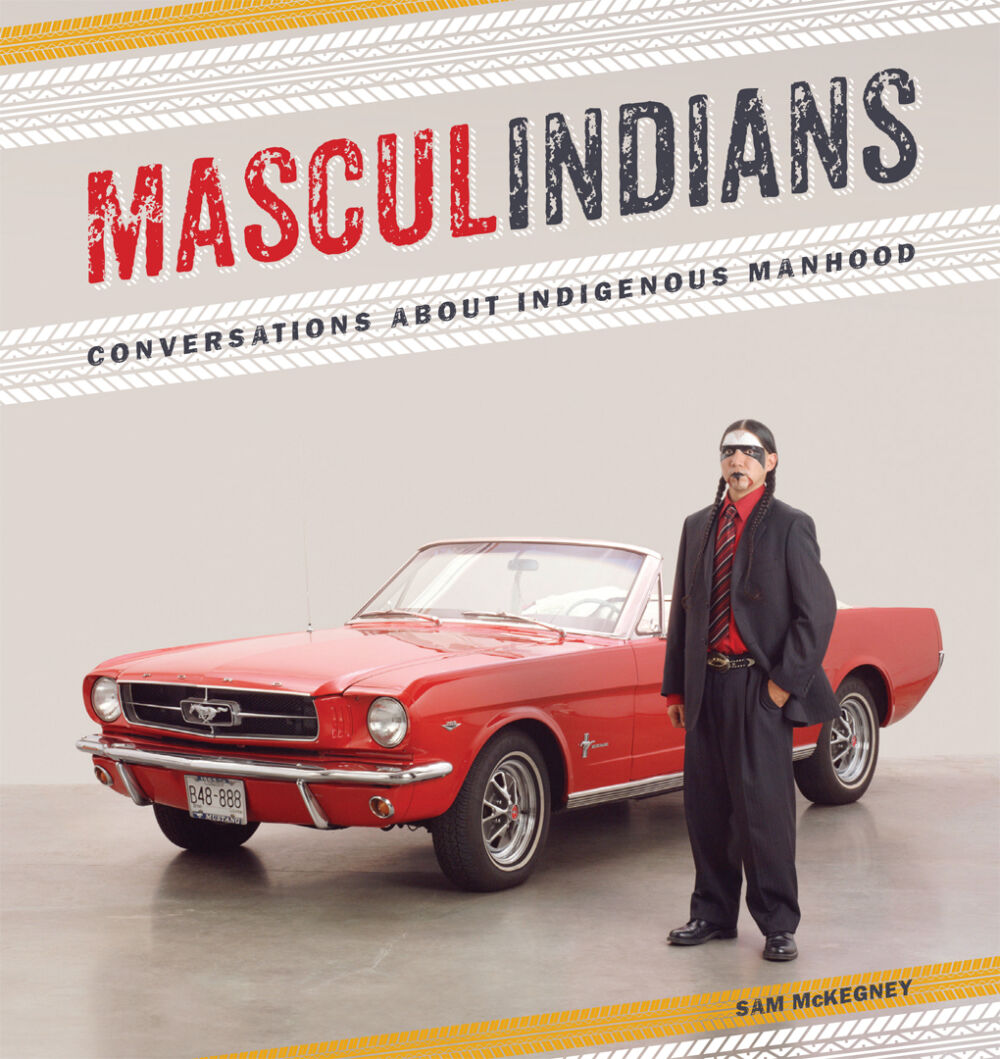

For more information on Masculindians: Conversations about Indigenous Manhood click here.

Posted by Sam McKegney

February 12, 2014

Categorized as Excerpt, Author Posts, Profiles

Tagged family, indigenous, male, masculinity, native

Let Them Trip "I may have an addiction to UMP's Immigration Series..."