In this Winnipeg 1912 excerpt, Jim Blanchard explores Winnipeg’s early development and growth as city deeply shaped by the technology of the railway.

In a relatable way, he describes Winnipeg’s early leaders’ initiative and vision in making sure the Canadian Pacific Railway ran through the city and brought people, jobs, and goods into Manitoba. At the same time, Blanchard illustrates how this technology manifested physically throughout the city with its many bridges, railroad yards, neighbourhoods, and businesses.

Although the railway no longer dominates the city and the province’s landscape to the extent it used to, it has deeply shaped Winnipeg and Manitoba both physically and ideologically in both rewarding and detrimental ways, and this is something modern Manitobans should understand.

*

Excerpt from “May: Railroads”

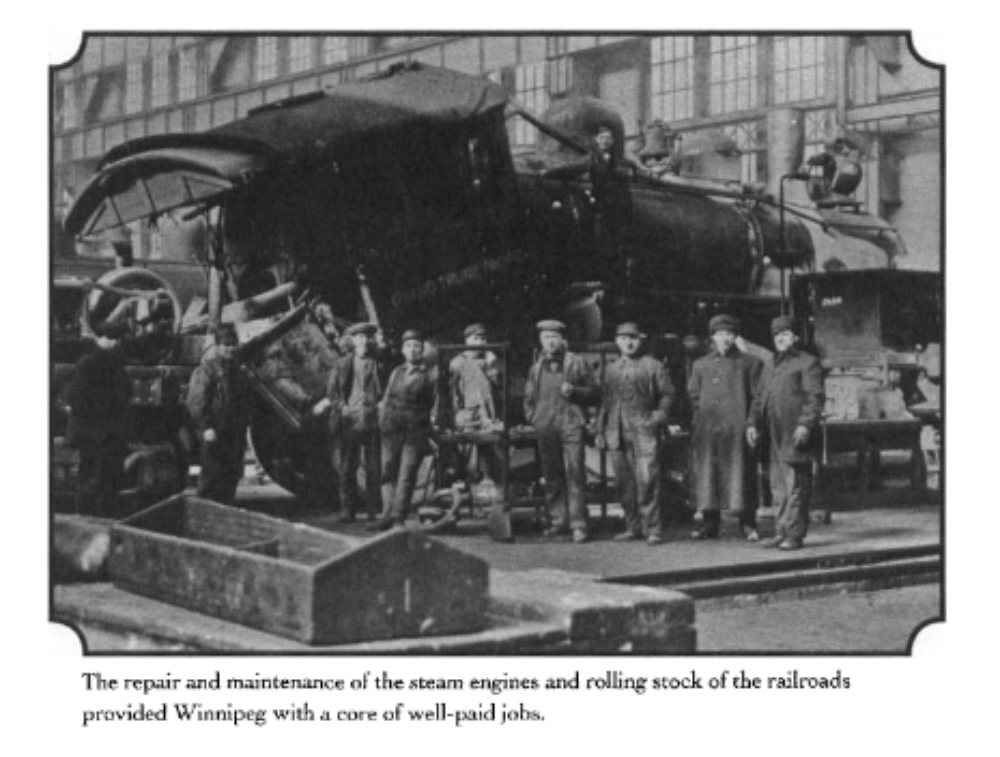

Winnipeg was the first and greatest of all the railroad towns that bloomed across western Canada. By 1912 over 4700 people in the city worked for the Canadian Pacific, the Canadian Northern, or the Grand Trunk railroads. Along with the grain business, manufacturing, and construction, the railroads were main engines of growth for the city.

Most of western Canada’s railroad towns sprouted in the cinders along the tracks in locations chosen by the rail companies. Winnipeg was different: she made the railroad come to her. As early as the 1860s, Winnipeg’s future elite, men like James Ashdown, John Schultz, and the editors of the Nor’Wester newspaper, James Ross and William Coldwell, began agitating for a railroad.

One of their first manoeuvres, in 1865, was to form an alliance with Sanford Fleming, the Scottish-born engineer who eventually laid out most of the CPR’s route across the west, and who achieved lasting fame for developing the system of time zones now used all over the world. Fleming had visited Red River as part of the Hind Expedition and he favoured the idea of a rail link with the east

The Winnipeg group presented Fleming with a memorandum, which he took to the government of Upper Canada, an early step in the long process of lobbying for and building the CPR. Twenty years later, in October 1885, he watched Donald Smith drive in the last spike of the CPR at Craigelachie in British Columbia.

For Winnipeg, it was important to ensure not only that a railroad was built, but that the main line passed through the city. Once again the city founders were successful in shaping events and, after much negotiation, they convinced the railway to divert its main line south from its westerly route and cross the Red River at Winnipeg.

They threw so many inducements on the table (including a $200,000 subsidy and payment for the bridge to carry the rails across the Red River) that the cash-strapped CPR could not resist.

In 1882 they also passed Bylaw 195, which provided that “all property now owned or that her matter may be owned by them [the CPR] within the limits of the City of Winnipeg for railroad purposes or in connection therewith, shall be forever free and exempt from all municipal taxes, rates and levies and assessments of every nature and kind.”

In addition to locating the main line through Winnipeg, the CPR also promised to build a 160-kilometre branch line southwest of the city and to erect a passenger station, freight yards, and shops within the city limits. The yards and shops were the most important influence on the early growth of the city. Canadian Pacific steam engines would be torn apart and rebuilt in the city and maintenance of all other sorts would be done there, so Winnipeg was guaranteed a large number of skilled jobs for machinists and tradesmen as well as labouring jobs and all the jobs in-between.

By 1912, not one but four railroads served Winnipeg. The stockyards and freight-handling facilities had given rise to other industries employing large numbers of people and producing fortunes for the local owners. Along a spur line that ran southwest from the Canadian Pacific yards just west of Arlington, for example, slaughterhouses and meat packing firms had been established. The largest of these was Gordon, Ironside and Fares, a company that shipped at least 50,000 head of cattle for export every year. In 1906 they shipped more animals than any other company in the world.

Dray wagons constantly moved in and out of the yards, hauling freight to and from the huge warehouses that lined the streets to the south. Although Winnipeg’s iron grip on the distribution trade had begun to loosen because of adverse decisions by the Board of Railway Commissioners and the steady growth of other prairie cities, in 1912 things were booming. Goods were unloaded in Winnipeg warehouses like those of J.H. Ashdown Hardware or the Gait’s Blue Ribbon grocery wholesale, and then shipped out to small stores all over the prairie. Every train that left the city carried commercial travelers who visited the small-town merchants regularly, taking orders and keeping everyone happy.

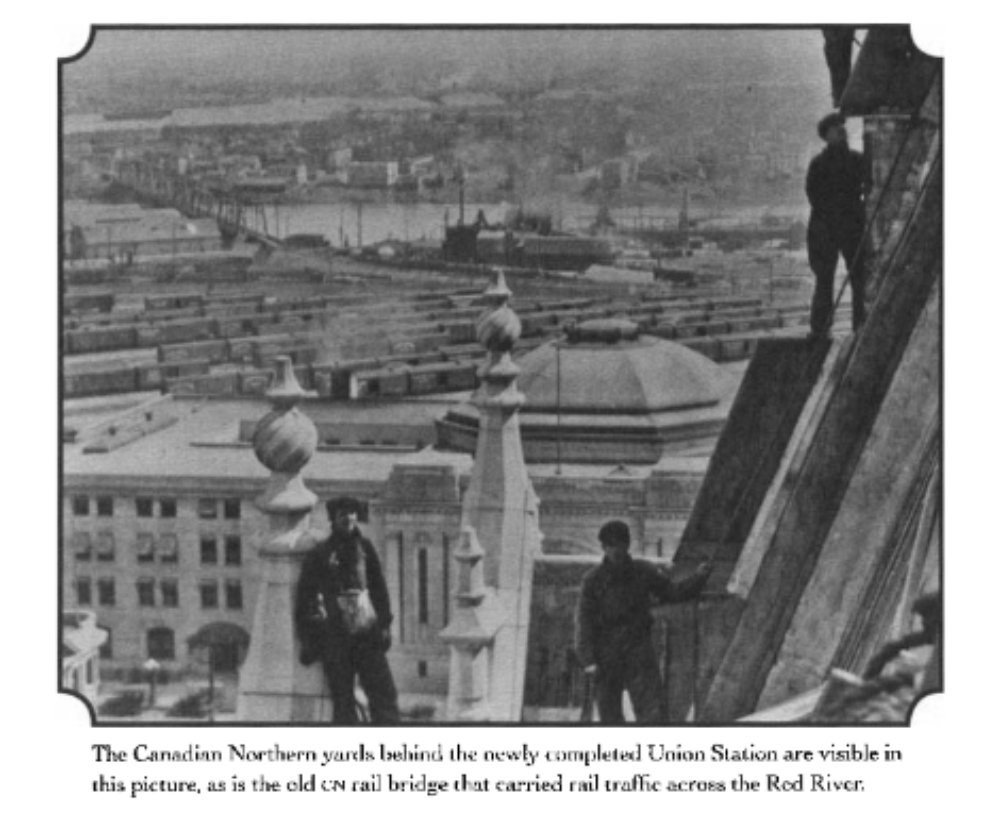

In addition to the enormous economic significance of the railways in Winnipeg, their payroll and spending for supplies and equipment, the presence of the companies had impacts of other kinds. Steam engines belching out smoke and dropping cinders and ash rumbled over sixty-four kilometres of rail running through many districts of the relatively small city. And there were the bridges that carried the various lines over the Assiniboine and Red rivers. The Louise Bridge on the site of the original CPR Red River Bridge was now a vehicle and pedestrian bridge and the CP main line crossed the Red a short distance upstream at the extreme east end of Point Douglas.

Further south along the Red, the spectacular new Grand Trunk Bridge with its unusual lift section was nearing completion. A little further along, the Canadian Northern Bridge crossed the Red at an angle and carried the CN line into the yards near the foot of Water Street. Turning at the forks and moving upstream on the Assiniboine, the Grand Trunk and Canadian Northern both had bridges crossing over into Fort Rouge from the yards. Farther west, almost at the boundary of the city, the Canadian Pacific, the Great Northern, and the Canadian Northern all had bridges crossing the river, the former two just west of Omand’s Creek, the latter at St. James Street.

The passenger schedules of the railroads brought over a dozen daily trains into the city and local Manitoba trains ran alternate days or twice a week. Each morning between 6:10 and 7:30, four passenger trains—the Prairie Express from Calgary, the Great West Express from Edmonton, the Imperial Limited from Vancouver, and the Soo Line train from the United States—pulled into the Canadian Pacific Station on Higgins Avenue.

Departures began at 8:00 a.m. when the Imperial Limited steamed out of the city, bound for Montreal. At 9:40 the Regina Express departed and then there was a lull until 1:15, when the Express train from Toronto came in. At 9:30 in the evening, the westbound Imperial Limited arrived from Montreal and the station was again crowded with passengers stopping in Winnipeg or boarding trains for Vancouver, Calgary, and Edmonton.

By midnight, all the westbound trains, including the sleeping car only on Imperial Limited, had left Winnipeg.

About Manitoba 150 Excerpts

May 2020 marks Manitoba’s 150 anniversary as a province of Canada. The Manitoba Act was passed by the Parliament of Canada and received Royal Assent on May 12, 1870, creating the Province of Manitoba. To celebrate, throughout the year we will be posting excerpts from some of our titles that touch on Manitoba’s history, people, and cultures.

Posted by U of M Press

July 24, 2020

Categorized as Excerpt, MB 150

Tagged 1912, canada, canadian pacific, community, cpr, history, labour, manitoba, manitoba 150, mb 150, prairie, prairies, railroad, railway, red river, winnipeg

COVID-19 Update July 10 Treasure hid in a field