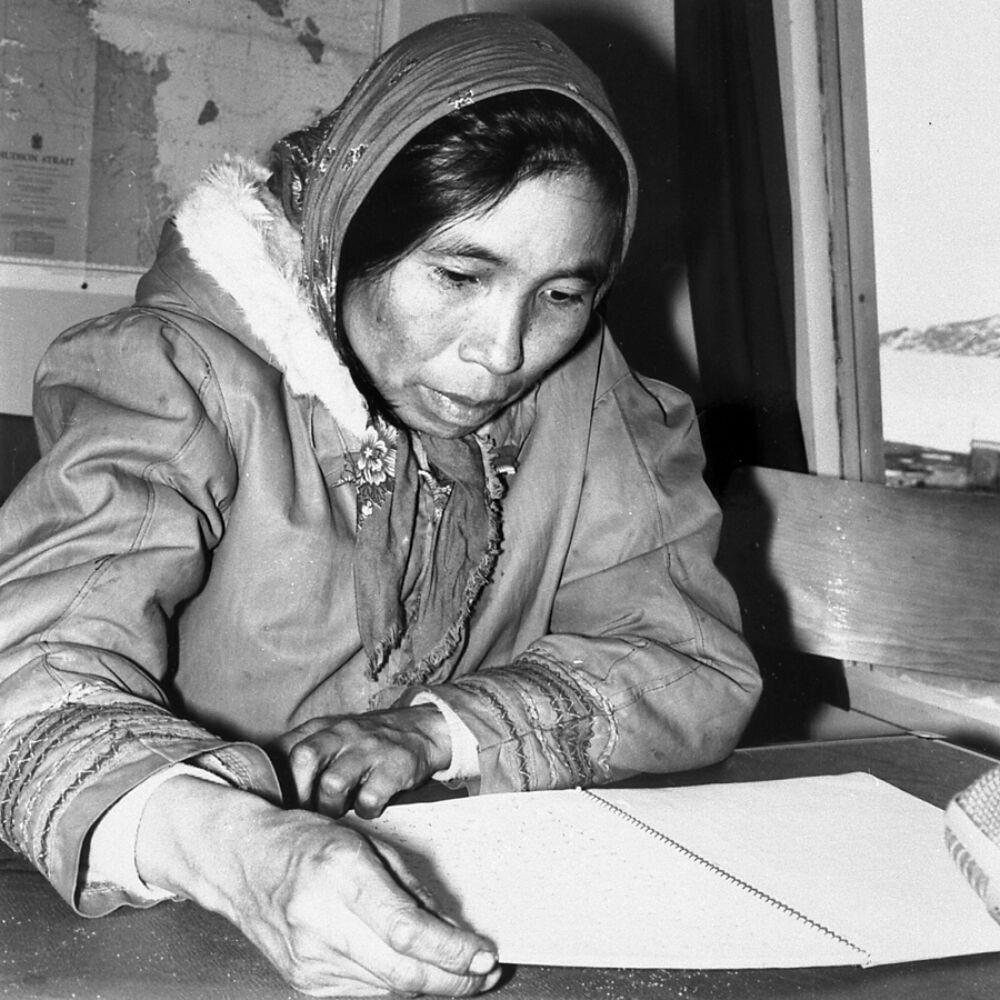

In the early 1950s, a young woman named Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk, living in Kangiqsujuaq, Nunavik, was asked by the Oblate missionary Father Robert Lechat to write down some Inuktitut sentences so that he could develop his vocabulary in the language. But Mitiarjuk soon carried this task beyond its pragmatic origins; fleshing out her descriptions of daily life with characters and plotlines, she ultimately produced a “novel” – a long work of fiction – that was published in Inuktitut syllabics in 1984. Mitiarjuk’s work has long been celebrated in Inuit communities, and while she received major honours before her death in 2007 – she was awarded an honorary doctorate from McGill and was named a Member of the Order of Canada – her writing has remained almost unknown amongst southern audiences, particularly in English-speaking Canada.

This month, however, that’s likely to change as the University of Manitoba Press, in partnership with Avataq Cultural Institute, releases the first English edition of Mitiarjuk’s novel, Sanaaq. Translated by Peter Frost from the 2002 French version, the book follows the life of a woman named Sanaaq and her family as they navigate not only their daily routine of child-rearing, visiting and harvesting food, but also the arrival of southern traders, medical professionals and rival Anglican and Catholic missionaries. The book maintains a lightness in tone when relaying even the grimmest of events, such as when the hunter Jiimialuk loses an eye to scalding water, only to hear Sanaaq’s young daughter ask whether she can eat the fallen cornea (the answer is no). As described in the preface by anthropologist Bernard Saladin d’Anglure, who worked closely with Mitiarjuk as she completed the manuscript, the author thus “reinvented the novel, even though she had never read one.”

[…]

But what’s going to happen when English-speaking audiences get their hands on this text? What if it doesn’t look like any other novel that they’ve encountered before? The novel, though seemingly ubiquitous, is in reality a genre with firm foundations in European history and ideology; it has been identified by various scholars as the flagship genre of individualism, of nationalism, and of capitalism. As the growth of the 18th century middle-class reading public created a wide market for publishers, the novel became a vehicle for ideas about national identity to disseminate and coalesce. And as Ian Watt explains, while “previous literary forms had reflected the general tendency of their cultures to make conformity to traditional practice the major test of truth…. This literary traditionalism was first and most fully challenged by the novel, whose primary criterion was truth to individual experience.”

The novel thus carries with it a certain set of expectations – typically, that it revolve around the innermost thoughts of a central character facing down a singular conflict. As Anthony Burgess declared somewhat haughtily in 1970, “The inferior novelist tends to be preoccupied with plot; to the superior novelist the convolutions of the human personality, under the stress of artfully selected experience, are the chief fascination.”

To hold Sanaaq to these criteria, then, may be as ethnocentric as those reviews that continually remark upon the “harshness” of the Arctic environment and of early 20th-century Inuit life. While it’s possible, as Saladin d’Anglure says, that Mitiarjuk had never read another novel, she was fully schooled in the literary traditions of her own territory. The result is a long work of prose fiction restrained in its exploration of the characters’ psyches; the reader must instead work to interpret their actions and dialogue, much as one might in listening to a traditional story. Sanaaq, meanwhile, is only one protagonist among many (indeed, the book’s original Inuktitut title – Sanaakkut Piusiviningita Unikkausinnguangat – makes apparent its focus on Sanaaq’s family). And in a manner that may baffle contemporary aesthetes, the book seems determined to retain its original usefulness, instructing not only southerners but also younger Inuit in the details of life as it used to be – and also in Inuktitut vocabulary. This version happily retains a strong use of Inuktitut terminology, requiring southern readers to either puzzle out the meaning from surrounding details or to flip to the glossary.

Posted by Keavy Martin

January 21, 2014

Categorized as In the News, Author Posts

Tagged art, artic, north, novel, quebec, traditions

Study Opportunity at Grassy Narrows First Nations Sanaaq in the Media