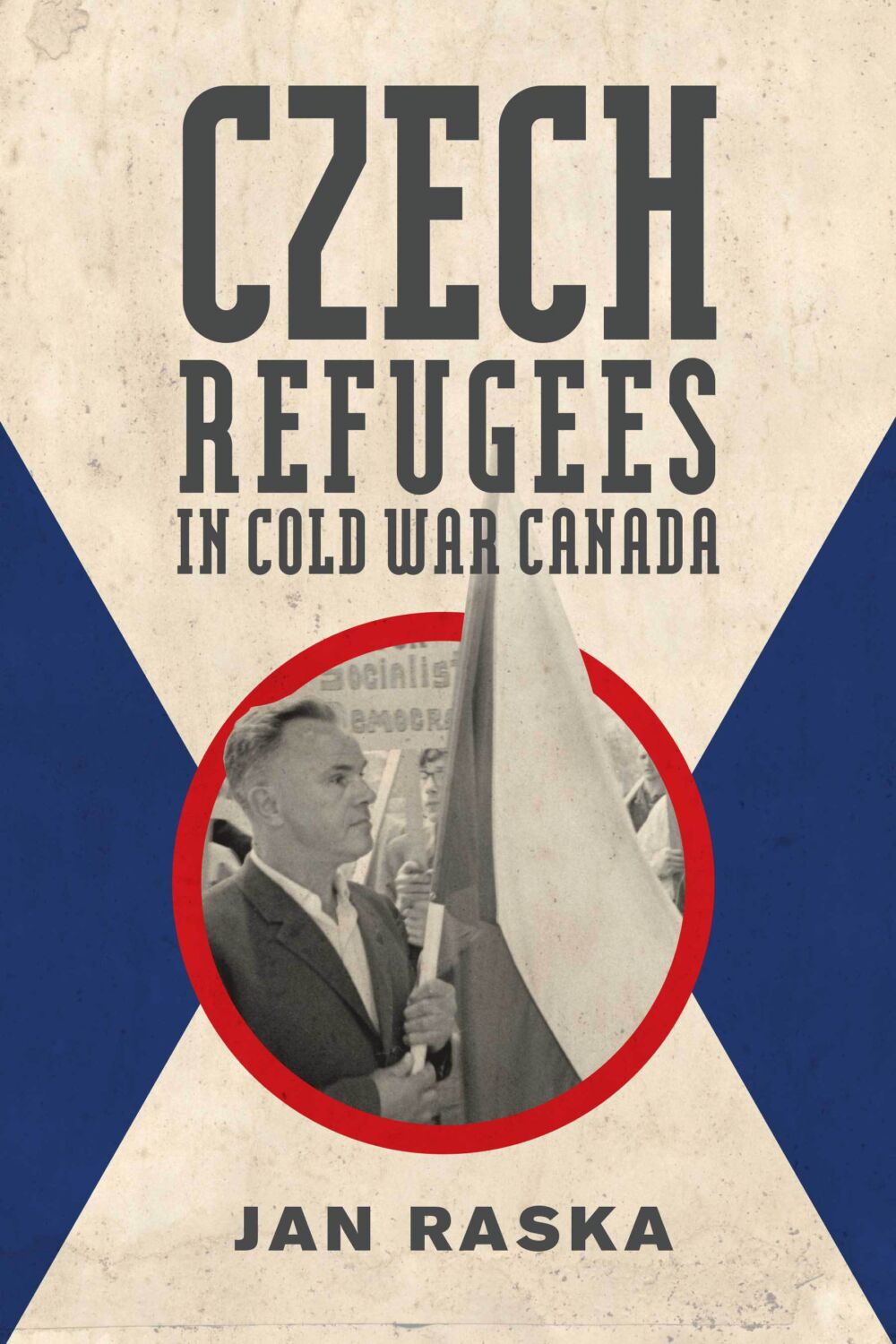

An excerpt from Czech Refugees in Cold War Canada:1945–1989.

Initially, my desire to learn about the shared past of Cold War refugees in Canada came from my own resettlement experience. In July 1985, just four years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, my family left Czechoslovakia in search of a better life and greater economic opportunities elsewhere. Like many Czech families, we applied for passports, in order to travel to communist Yugoslavia for “a vacation.” It was the only way for most individuals and families to leave Czechoslovakia. After we drove through Hungary and arrived in Yugoslavia, my parents sent a letter informing their siblings of our departure, and we left our possessions to them before the communist authorities became aware of our emigration and confiscated them.

In Yugoslavia, we spent the first two weeks near the Adriatic Sea in Croatia. We eventually left for Belgrade and stayed there for several days in a motel where other refugees from Eastern Europe were awaiting permanent resettlement in the West.

In the Yugoslav capital, my parents applied for refugee status, under the United Nations Refugee Convention, with the local office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

During their interview with a UNHCR official, my parents were asked why it had taken them two weeks to request refugee status. They informed the official that they had wanted to visit the Adriatic Coast before heading to Belgrade. The visibly annoyed official, who had handled hundreds of similar cases, subsequently denied our claim for refugee status.

My parents were later informed by other refugees at the motel that they should have stretched the truth or fabricated a believable story in order to acquire refugee status. Without options, my father reached out to his sister, who had immigrated to Canada in the late 1960s.

In November 1985, we left Yugoslavia for Canada. Our journey involved a transatlantic flight from Belgrade to Montreal. After landing in Canada, immigration officials asked my parents how we pronounced our family name, Raška (pronounced Rash-ka), since no háček (a diacritical mark placed over certain letters in the Czech alphabet) existed above the letter ‘s’ in the English language. The officials informed my parents that they could anglicize their surname to Rashka, or they could keep it the same, but the pronunciation would inevitably change. We eventually resettled in Ottawa and embraced our new Canadian home. Prior to receiving Canadian citizenship less than five years later, we officially chose to keep Raska as our family name.

Over the years, my parents have often told me stories about our journey to Canada. I soon began to consider the similarities and differences that our immigration experience had with other individuals and families from Eastern Europe, especially Czechs who came to Canada after the 1948 communist takeover of Czechoslovakia and the 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion. Although their motivations for leaving Czechoslovakia and resettling in Canada were diverse, they were often viewed by successive generations as individuals who had left their homes because of political persecution and everyday life under a totalitarian regime.

Yet this story was not drilled into me. As a youth, I attended summer camps in the Laurentian Mountains, where I spoke Czech, played sports, sang traditional songs, participated in the calisthenic exercises of the patriotic Sokol (Falcon) movement, and was taught about my ethnocultural heritage with other young Czechs. Apart from these early ethnocultural experiences, my family did not regularly participate in community events. I am well aware that my status as a community “insider-outsider”—a Canadian of Czech ancestry not active in community organizations—provides me with a unique lens through which to examine the history of Czech immigration to Canada during the Cold War.

In seeking insights into Czech refugee experiences in Canada, I began to collect stories, oral histories, archival documents, photographs, and published materials, no matter their political bent. I later learned that, during the Cold War, 36,531 individuals claimed Czechoslovakia as their country of citizenship upon entering Canada.

But, more importantly, I discovered that a defining characteristic of this postwar migration of predominantly ethnic Czechs and Slovaks was the prevalence of anti-communist and pro-democratic values. Diplomats, industrialists, workers, politicians, professionals, and students spoke about fleeing to the West in search of freedom, security, and economic opportunity. It was important to them that they might permanently resettle in Canada and become naturalized citizens. Yet it was never quite that simple. According to the 2016 Canadian census, 104,580 Canadians reported having full or partial Czech ethnicity. Closer analysis reveals that 81,330 Canadians claimed multiple ethnic origins, while 23,250 Canadians indicated having only Czech origins. Meanwhile, 40,715 Canadians reported having Czechoslovakian heritage. The Czechs and the Slovaks formed separate ethnocultural groups. During Czechoslovakia’s existence from 1918 to 1992, a majority of Slovaks opposed a common “Czechoslovak” nationhood often promoted by Czechs and a minority of Slovaks.

Existing scholarship on Slovak immigration to Canada has examined the postwar experiences of Slovak refugees in Canada. However, there remains a dearth of scholarship on Czech refugee experiences in Canada after the Second World War. As a result, a number of questions soon permeated my thinking about their immigration to Canada during the Cold War. Since many of these newcomers were political refugees, who were they? What made them choose Canada? When did they arrive in Canada? How did the Canadian government and local Czechoslovak community institutions influence their immigration and resettlement experiences? How did they create an identity that would make them welcome refugees in Canada?

Czech Refugees in Cold War Canada is the first full-length academic study of post–Second World War Czech immigration to Canada. It examines the admission, resettlement, and integration of Czech refugees during the Cold War. In using archival records and oral histories that illustrate diverse refugee experiences, I shed further light on the immigrant experience in Cold War Canada, ultimately demonstrating that refugees and their families were preoccupied with forging identities that would lead to their acceptance.

They were intent on showing Canadians, the Canadian government, and their own compatriots that they were middle-class anti-communists beyond either Old World nationalism or subversive leftist agitation. By exposing the totalitarian nature of their homeland and the reasons for their forced migrations to the West, Czech refugees in Canada attempted to legitimize their experiences and navigate the Cold War norms found in their new country. For individuals and families who immigrated from Eastern Europe to Canada, the fear of being labelled communist sympathizers or Soviet spies and put under state surveillance became a significant factor in how they handled the moral panic in Canadian society about the global spread of communism and Soviet influence. These individuals soon used pro-democratic and anti-communist rhetoric not only to appease Canadian officials and the greater public—suspicious of immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe because of preconceived notions about ethnoracial identity, work ethic, and ability to assimilate—but also to demonstrate their support for the cherished Canadian ideas of freedom, liberty, human rights, and democratic values.

Posted by Jan Raska

September 27, 2018

Categorized as Excerpt, Author Posts

Tagged cold war, community, czech, czechoslovakia, excerpts, history, immigration, political refugees

Sounding Thunder now an opera! Orange Shirt Day Booklist!