In this excerpt from mmm... Manitoba, authors Kimberley Moore and Janis Thiessen discuss the introduction of the perogy to the prairies—and Manitoba's illegal underground perogy market (pages 87–95).

Unlawful Perogies

Ukrainian immigrants first arrived in Manitoba in 1891, settling throughout the province in the towns of Stuartburn, Whitemouth, Shoal Lake, and Dauphin as well as Winnipeg. Perogies were one of the food traditions they brought with them. These dumplings were labour-intensive but also cheap to produce, and often eaten by Ukrainian Catholics on Fridays when their faith required them to abstain from meat. As a food that was both affordable and filling, perogies were popular throughout the southern half of the province where Ukrainian Canadians lived in great numbers. As a “peasant food” not readily available in Manitoba restaurants until the 1970s, Manitobans, for much of the twentieth century, had either to make their own perogies or buy them from a local “perogy pincher.”

Perogy pinchers are typically women who adapt their cooking skills to provide for their families not only by preparing meals for them but by (usually illegally) selling food made in their homes to others. The underground food economy muddies the distinctions between familial, community, and commercial food, between domestic and marketable production. Household food entrepreneurs have a long history in Canada, and many Manitobans have a “perogy lady” from whom they buy homemade perogies. There is little information available about these women. As food studies scholar Irena Knezevic notes, “The fuzzy edges of informal economic activities make them difficult to study.” The occasional newspaper tribute, classified advertisement, or obituary is seemingly the only print evidence of their existence.

Many perogy ladies continued to produce perogies in their homes for sale well into their golden years. Stella Barta was described in the local newspaper as “Hadashville’s perogy lady.” At age seventy-five, she was “still going strong pinching and cooking those yummy perogies known well to the west in Winnipeg and to the east in Kenora.” Her home production was described by the journalist as “her perogy factory.” Mary Stelmack was similarly labelled as Marchand’s “perogy lady.” Jean Wensel taught perogy making at a Winnipeg high school’s home economics class, and, as her obituary stated, “after retirement from Eaton’s, went on to begin a small, home-based perogy and pie business. There was never a shortage of customers.”

Classified ads reveal the historical popularity of perogies as a cottage industry. An ad in the Selkirk Journal featured a twenty-quart dough mixer, described as “perfect for bakeries, restaurants, or perogy sellers.” Two unnamed but “experienced ladies” advertised in the Winnipeg Free Press that they were willing to “fill orders for delicious homemade perogies and holubchi” (holubchi are cabbage or, less commonly, beet leaf, rolls). Others advertised that they had for sale “fresh cabbage rolls and perogies” or “perogies & home-made bread.” One simply declared that they were willing to “make perogies on weekends." These are only a few of the many perogy pinchers who, for decades, have sold perogies out of their homes in Winnipeg’s North End, the Interlake, southern Manitoba, and the Parkland—indeed, almost every corner of the province, including Churchill. Ukrainian Manitobans from Birch River moved to Churchill and brought their food traditions with them. Helen McEwan, peer coordinator at the local school, explained that Churchill has “a really strong perogy community. So, everyone has kind of their own traditional ways of doing things and there’s [work] bees that get together [to make perogies] and stuff.”

It is illegal to be a perogy lady in Manitoba; the province prohibits the preparation and direct sale of food from home-based businesses, whether through word of mouth or websites or social media. Under the province’s Farmers’ Market Guidelines, only home-produced food that is not considered potentially hazardous food may be sold, and then only at a permitted market. Potentially hazardous food is defined as “any food that consists in whole or in part of milk or milk products, eggs, meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, edible crustacea, or other ingredients, including synthetic ingredients, in a form capable of supporting rapid and progressive growth of infectious or toxigenic micro-organisms, but does not include foods which have a pH level of 4.6 or below or a water activity value of 0.85 or less.” Permitted markets are “a short-term operation for the sale of produce and prepared food products under the direction of a designated Market Coordinator,” such as farmers’ markets, “flea markets, craft sales, bake sales and other such establishments.” The market itself requires a permit; vendors at the market selling potentially hazardous food must have produced it in a permitted commercial facility such as a community kitchen. Potentially hazardous food includes “homemade perogies, cabbage rolls, sandwiches, and cream-filled pastries” but not “jams, jellies and pickles with a pH of 4.6 or lower.” The sale of “unpasteurized milk, ungraded eggs, wild mushrooms, uninspected meat or poultry” is never permitted at such markets.

To produce perogies and other potentially hazardous foods for sale in Manitoba, a commercial kitchen, a health permit, and regular public health inspections of facilities are required to ensure the safety of the products made. The Public Health Act’s Food and Food Handling Establishments Regulation requires those who “operate a food handling establishment” have a permit unless they produce only non-potentially hazardous foods. This provincial regulation also restricts the ability of Indigenous hunters in the province to sell wild game, and prevents Indigenous restaurants from offering country food on their menus: only inspected meat may be sold in Manitoba. While individuals can process game animals and birds for their personal consumption without inspection, such game can be served to the public only with provincial permission “for special occasions or under special circumstances.” This regulation also places limits on the kinds of cheeses that may be produced in the province, as no unpasteurized milk products are permitted—a particular frustration for those attempting to carry on the tradition of Manitoba Trappist cheese making.

Winnipeg’s first bylaws addressing food were made shortly after the creation of the province in 1870. Grocers, taverns, and hawkers were licensed as early as 1874. The city’s first health inspector, D.B. Murray, was appointed in 1875; he also served as chief of police at the time. A bylaw to establish and regulate public markets was enacted the same year; it was amended in 1877 to regulate who would be allowed to sell meat and fish, though a fish market was established the following year. The first food, drug, and agricultural fertilizer inspectors in Winnipeg were appointed in 1894: Mac S. Inglis, Benjamin F. Fairclough, and Alexander Polson. There must have been some issue with subsequent appointments, as a bylaw was passed in 1913 requiring that “all persons in future appointed as Sanitary Inspectors shall be properly qualified.”

Regulations governing perogy production and other types of “cottage food” or home-based food production vary from place to place. Since 2016, Saskatchewan permits direct sale to the public of non-hazardous home-based foods; they are the only Canadian province to do so. Saskatchewan residents can now sell jam and cookies (for example) via social media directly to consumers, retailers, and wholesalers and not solely through farmers’ markets. Home-based perogy sales are not permitted, however, as they are considered a potentially hazardous food. In the United States, New Jersey prohibits all cottage foods, whereas Wyoming and North Dakota have virtually no restrictions on their production. Policy analyst Jennifer McDonald surveyed 775 cottage food producers in twenty-two of the twenty-six American states that permitted cottage food production. She found that these producers were “primarily women who live in rural areas, have below-average incomes, and operate their businesses as a supplemental occupation or hobby.” As a result, she argues, those “concerned about expanding female business ownership and improving rural well-being should consider expanding cottage food laws to encourage the industry to flourish.”

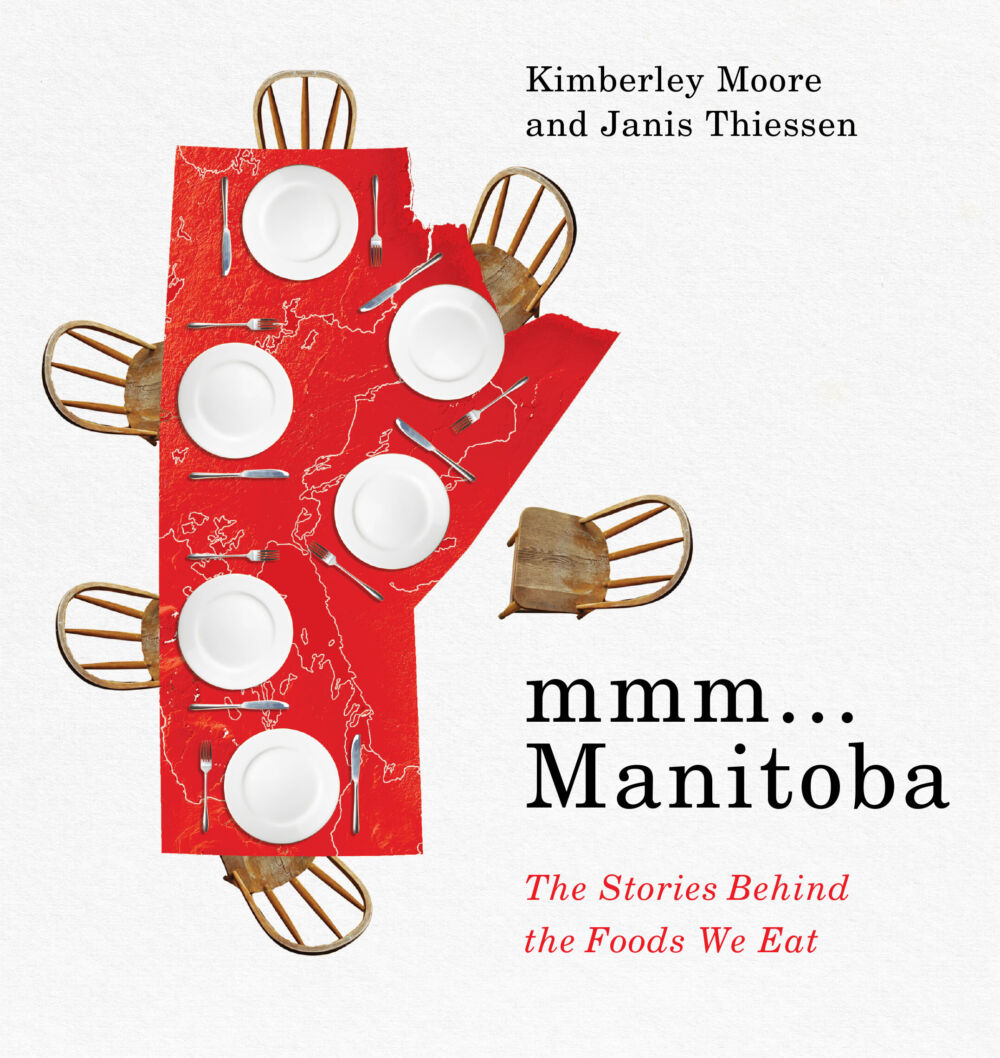

mmm... Manitoba is available for pre-order now!

mmm... Manitoba

The Stories Behind the Foods We Eat

Kimberley Moore (Author), Janis Thiessen (Author)

Mixing recipes, maps, archival records, biographies, and full-colour photographs with fascinating stories, mmm... Manitoba showcases the province’s diverse foodways and industries from on board the Manitoba Food History Truck.

Posted by U of M Press

February 16, 2024

Categorized as Excerpt

Around the Kitchen Table: Excerpt The Honourable John Norquay Events