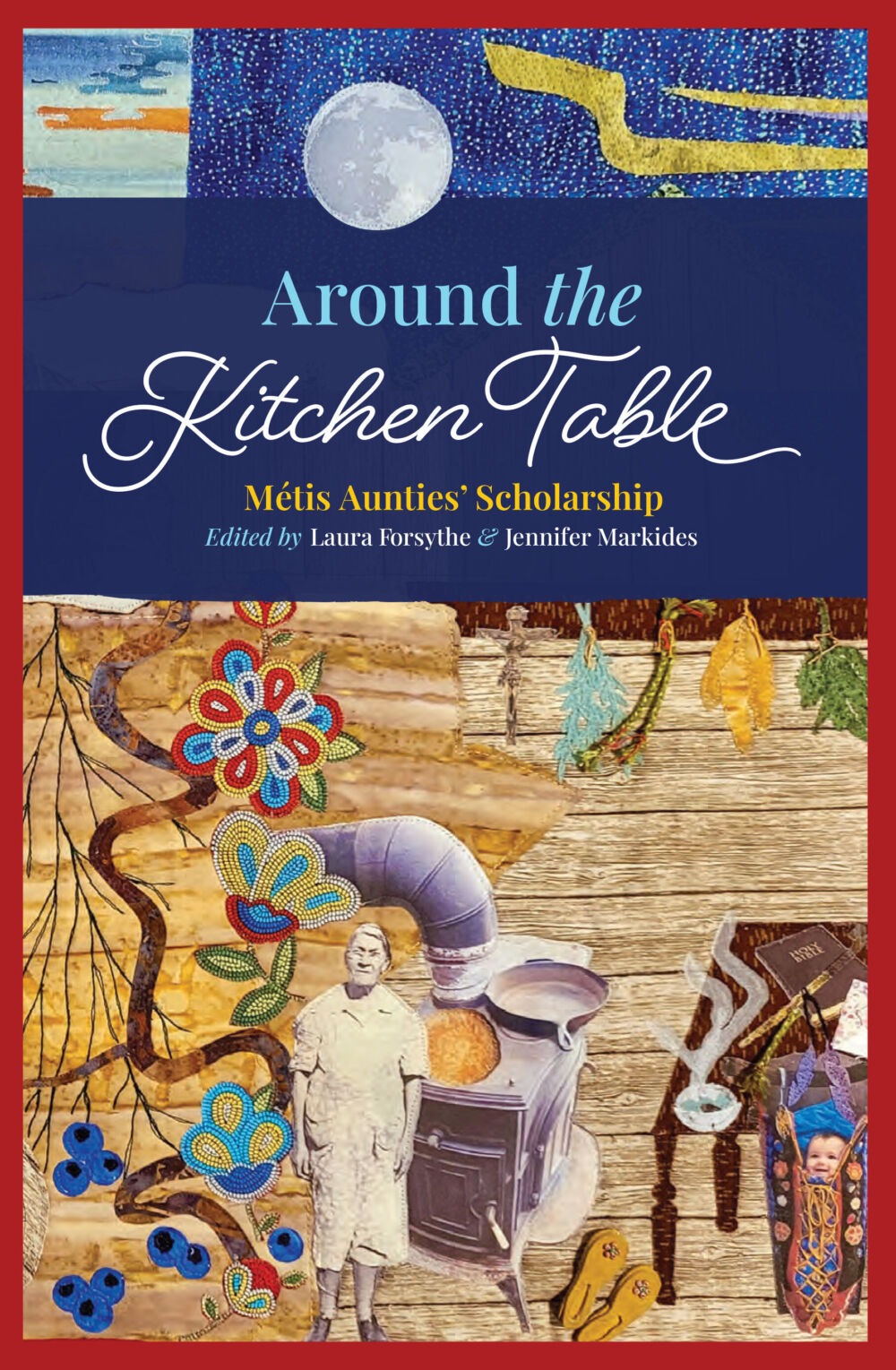

"This book stands as a testament and tribute to the strength of the Métis/ Michif matriarchs who have come before us and is a gift for the future generations we hope to teach, mentor, reclaim, walk alongside, and inspire."

Read the following excerpt from Jennifer Markides' introduction to Around the Kitchen Table edited by Laura Forsythe and Jennifer Markides, pages 1–4, and the poem "Medicine Woman" by Jennifer Adese, pages 84–86.

The Work of Métis Women: An Introduction

By Jennifer Markides

In this opening, it would be easy to focus on the ways the hegemonic and paternalistic legacies of colonization have occluded the stories of Indigenous Peoples, and in particular Indigenous women, from prominence in life and from the pages of Canadian history for hundreds of years. From our very beginnings in Red River to the days of road allowances, scrip, and beyond, Métis people have been marginalized, displaced, and discounted. Documentation of our people has focused on the stories of men—fur traders, rebels, and leaders—with women assumed to be in the background of our societies. However, we know our stories differently than they have been told. Strong Métis women, inclusive of two-spirit kin, have shaped our communities, culture, and identities with agency.

Perhaps usefully or stubbornly, this introduction serves as a touchstone or route marker for what is ahead and does not include a literature review or standard citations. Instead, the entirety of the book is the source of inspiration and the wellspring of scholarship that has informed these first passages. Why bend to academic conventions? Rebellious blood flows through these veins. As a point of process, this opening reflects dwelling with the chapters—listening and learning, gathering, and then listening again until the individual ideas and sensory stimuli fade into an abundantly satisfying cacophonic experience. Like saskatoon berries bursting in your mouth, after having stained your hands. In theory, you should feel the presence of the authors and their stories if you were to reread this setting again at the end. Their voices—ideas, teachings, discoveries, witticisms, inspirations, suggestions, influences, and rich descriptions—mingling, indistinguishable from each other, pleasantly so. A community of Métis thought.

In walking the Red River path, we bring this collection together so that the generations of Métis who come after will have a well-tended trail to travel. For many Métis, the consequences of colonization have included both temporal and physical displacement from identity and community. Fortunately, this has not been the experience of all Métis. Those who have maintained cultural and community connections generously support the reclamation of kinship relations through knowledge sharing. Learning our stories, histories, language, and cultural practices are ways Métis foster individual and collective identities. Teachers come in many forms, including our Métis family and community members, archives, scrip and census documents, cultural artifacts, kokums, Elders, academic aunties, peers, and the land.

While some Métis might still be searching for clues to identity, culture, and belonging, the gathering of our stories and practices is well underway. The Métis intellectuals whose work is shared in this book have researched to uncover the beads of our shared histories, addressed the gaps in Métis literature, recognized and celebrated our matriarchs, shown reverence for our kitchen table pedagogies, and reimagined our relationships with land as a place that is known in our histories and hearts. They have moved beyond the oft-heard narratives of Métis being a displaced people, to a discourse of Métis as relationally situated and deeply rooted. The contributions exemplify Métis scholars’ assertions of epistemological self-determination.

Métis have maintained robust relationships to values and ways of being that are distinctly ours. As a matrilineal society, our matriarchs have been the leaders, role models, mentors, mothers, aunties, grandmothers, sisters, and cousins. Many of whom have resisted the assimilatory efforts of colonization; relocated geographically but remained steadfast in Métis ways; reclaimed our stolen, lost, and wandering kin in warm embraces of education, responsibility, and love; retained our Michif language in the numerous dialects and variations; maintained strong bonds across religious and other differences; and sewed the sinew that has bound us together in culture and place—beads set with intention—connected in powerful dynamisms with purpose and pride.

Picking up the connective threads, you will find that the Michif language is embedded within many of the chapters in this text. Spelling of words varies across communities but often holds the same or similar meaning, as in the case of the term of Cree origin: wahkotowin, wakotowin, wahkohtowin, wahkootowin, which signifies our being in relationship to one another and holds us accountable to our kinship relations. These are not spelling mistakes, and we do not seek to unify the book with a common version of shared words. Like our matriarchs have modelled, we embrace these differences.

Other strands woven through many of the chapters include references to the work of Maria Campbell, Brenda Macdougall, Marilyn Dumont, Gregory Scofield, and Sherry Farrell Racette, to name a few. Some authors reference other contributors to the book, including Emma LaRocque, Vicki Bouvier, and Nicki Ferland. As Laura Forsythe’s chapter highlights, being able to cite Métis people when researching Métis-related topics has only recently become possible.

Evidenced throughout the pages that follow, Métis are resilient, resourceful, creative, and courageous. We have been taught to be flexible, hard-working, and supportive of one another. We learn from listening, observing, helping, and doing. With beading, sewing, preparing meals, tending to children, telling stories, and sharing our gifts, there is no time to be idle.

We invite you to join us, from across the homelands, to listen with your heart, body, mind, and spirit—open these channels with senses heightened. Hear the unmistakable heartbeat of the Métis fiddle music and the pounding of moccasins on the wooden floor. Taste the meats, berries, and teas around the kitchen tables. Smell the wood-burning fires, hand-picked medicines drying on rafters overhead or smouldering in healing ceremonies, and the ancient soil being unearthed to reveal a blue bead that will transport you in time and place. See the patchwork of rag rugs and scrap quilts, the colours of the Métis ribbon skirts and ornately beaded moss bags. Witness the stories told through beads purposefully placed in intricate forms as teachings handed down.

Learn alongside Elders, friends, sisters, aunties, and cousins.

This book stands as a testament and tribute to the strength of the Métis/ Michif matriarchs who have come before us and is a gift for the future generations we hope to teach, mentor, reclaim, walk alongside, and inspire. May we honour the tireless work of Métis women and take up our places as leaders, educators, mothers, and storytellers who remain committed to upholding our language, culture, place, and sovereignty. Towards a good life.

Medicine Women

By Jennifer Adese

My contribution is a departure from my usual kind of writing. Academic writing could only carry me so far. What appears below is a poem—a single poem—honouring some of the Métis women who have shaped and continue to shape my being in this world and the gifts that they have given me and so many others. They are some of the women who have welcomed me home, who have worked to heal me, and who helped me find my place in the world as a Métis woman. The poem is part grief and gratitude, as each of these women have passed on to be reunited with our ancestors.

Marge

I heard your voice behind me, smoky and rich

cadence rising as the rickety school bus carried us

along the gravel road to the conference

your laughter cracked with joy

the way sun breaks through clouds after a rainstorm

a woman

who knew that Laughter is medicine

Rose

I saw you reach, arms outstretched

to welcome me as your cousin

your smile widened from across the meeting room

like our grandmother in the sky,

beaming eyes reflecting the essence of the stars

a woman

who knew that Family is medicine

Auntie Helen

I smelled your bannock, baking

wafting over the suitcase of family photos

kids from the rez would come hungry to your door,

asking “Kokum do you have some bannock?”

I was hungry, too, so you said to call you kokum

a woman

who knew that Love is medicine

Shelley

I tasted the peanut butter squares, chewy

like that time in Athabasca with your branch

family reconnected, you laughed at me, asking,

“Cousin, who wears ballet flats to a farm?” and

“Who kisses a farm dog on the head?”

a woman

who knew Humility is medicine

Grandma

I tenderly caressed your hair, silvered strands

fingers sliding as if time through an hourglass

that would far too soon run out. I broke.

your frail body hurled sandbags,

stemming the flood with a whisper, “Don’t cry”

a woman

who knew that Grandmothers are medicine

Around the Kitchen Table

Métis Aunties' Scholarship

Laura Forsythe (Editor), Jennifer Markides (Editor)

Looking beyond the patriarchy to document and celebrate the scholarship of Métis women, Around the Kitchen Table brings together writing by new and established scholars, artists, storytellers, and community leaders that reflects the diversity of research created by Métis women as it is lived, conceptualized, and re-imagined.

Posted by U of M Press

February 16, 2024

Categorized as Excerpt

University of Manitoba Press is hiring a term Editorial Assistant mmm... Manitoba: Excerpt