In February, Adele Perry asked her HIST 2282: Inventing Canada class at the University of Manitoba to work on a commemoration project after reading Evelyn Peters, Matthew Stock, and Adrian Werner’s Rooster Town: History of an Urban Métis Community, 1901-1969. We will be posting all ten projects over the coming weeks.

Group 1: EA, DC, LD, SF, SH, BP, A

For our group project, we decided to further research the media’s prejudicial representation of Rooster Town’s Métis residents.

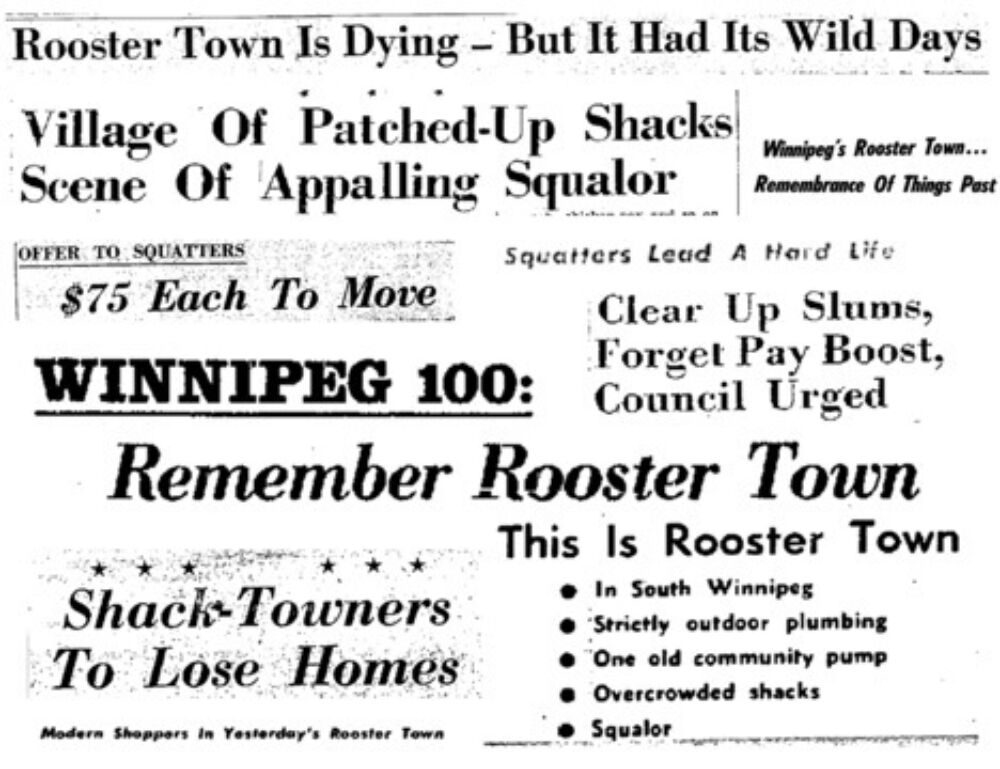

In the book Rooster Town, Evelyn Peters et al. emphasize that the 1950s “ushered in prying and sensationalist reports by two of Winnipeg’s major daily newspapers, the Winnipeg Free Press and the Winnipeg Tribune.”

These publications tended to construct ideas of Rooster Town using Eurocentric assumptions of Métis peoples, and their presumed inabilities to adapt to modern ways of living. The media suggested that these residents were unfit for life in urban cities, by using “descriptions of ‘squalor,’ ‘filth,’ ‘dilapidated shacks,’ and ‘bedraggled children’” within their reports.

Moreover, the articles “blamed their poverty and marginalization on their lack of ambition,” citing that “Rooster Town residents were satisfied with their situation.” Notably, these claims broadcasted colonial attitudes of Indigeneity and their aversion to successful Métis communities. As Peters et al. articulate, “using self-interested colonial reasoning, John Dafoe described Rooster Town as a threat because suburban development was encroaching on the community.”

Despite these attempts to ostracize the Métis residents of Rooster Town, within daily newspaper reports, it is apparent that the “failure to acknowledge a colonial history of dispossession” inhibited non-Métis peoples’ abilities to perceive the viability and cultural hub that was Rooster Town.

Furthermore, the relatively untold testimonies of Métis residents reflect the positive aspects of Rooster Town. Métis and non-Métis peoples alike recognized fiddling, jigging, partying, visiting, and supporting one another as “common social practice in the community.” Conversely, “newspapers broadcast[ed] the negative aspects of Rooster Town gatherings, [as] these cultural and community-based activities were not of interest to reporters.”

The act of neglecting these realities of Rooster Town and its residents from the media, suggests one of the City’s attempts to ‘other’ the Métis, and eradicate Indigeneity.

Considering Métis peoples of Rooster Town were depicted so poorly in the media, our group wanted to commemorate them by opposing these derogatory stereotypes. In the book Rooster Town Evelyn Peters et al. highlight several newspaper articles that reported harmful assertions towards Rooster Town’s residents.

As Canada, and more specifically, the City of Winnipeg has yet to commemorate Rooster Town as a viable Métis community, our group wanted to showcase the genuine families behind these stereotypes.

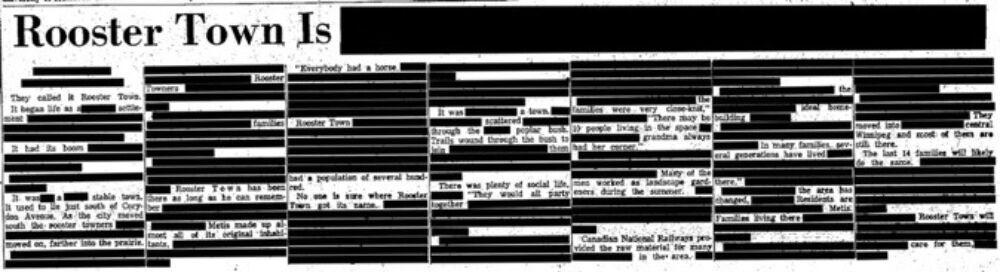

We thought it would be a good idea to compile various newspaper articles, that we sourced from the Winnipeg Free Press Archives, and use black-out poetry techniques to physically erase the Eurocentric and racist assumptions within these accounts of Rooster Town.

In removing certain words, one can create robust and genuine depictions of Rooster Town and its history, to portray the realities that these newspapers neglected. In itself, Rooster Town can be considered a form of commemoration; however, before its publication, the history of this community was essentially forgotten. By creating an illustrative piece of commemoration, that identifies the real histories of these sociable, hardworking and proud Métis peoples, we can rewrite this history, to better reflect the authenticity of Rooster Town.

Our group thought it best to actualize this concept in a classroom-setting, so students of elementary to high school ages could get to know the histories of Rooster Town and create their own interpretations of this narrative. Furthermore, the mobility of this form of commemoration has the possibility to reach a broader audience as we can bring the materials to them, instead of having to relocate to the site of Rooster Town to view a commemorative plaque, for example.

The creative aspects of black-out poetry may allow the student to be more interactive with the histories and narratives of Rooster Town, as it creates a hands-on approach to commemorating this Métis community.

About Rooster Town

Melonville. Smokey Hollow. Bannock Town. Fort Tuyau. Little Chicago. Mud Flats. Pumpville. Tintown. La Coulee. These were some of the names given to Métis communities at the edges of urban areas in Manitoba. Rooster Town, which was on the outskirts of southwest Winnipeg, endured from 1901 to 1961.

Those years in Winnipeg were characterized by the twin pressures of depression and inflation, chronic housing shortages, and a spotty social support network. At the city’s edge, Rooster Town grew without city services as rural Métis arrived to participate in the urban economy and build their own houses while keeping Métis culture and community as a central part of their lives.

In other growing settler cities, the Indigenous experience was largely characterized by removal and confinement. But the continuing presence of Métis living and working in the city, and the establishment of Rooster Town itself, made the Winnipeg experience unique.

Rooster Town documents the story of a community rooted in kinship, culture, and historical circumstance, whose residents existed unofficially in the cracks of municipal bureaucracy, while navigating the legacy of settler colonialism and the demands of modernity and urbanization.

Posted by U of M Press

March 31, 2020

Tagged colonialism, commerating rooster town, community, history, indigenous, metis, rooster town, urban metis, winnipeg, winnipeg history

COVID-19 Update March 23 Commemorating Rooster Town: Group 3